When students return to schools and colleges after the Covid-induced break from the ‘normal’ structures and routines of teaching-learning, would they be encountering merely what they used to know earlier? Or would the new means popularised during the pandemic find ways to blend into the older, time-tested ways of our educational institutions, opening up possibilities of overcoming aspects of the traditional system that were detrimental to the best interests of learners? How will social inequities reinforced during the pandemic through inequality in digital access affect the nature of challenges various sections of students face when they return to schools and colleges? How will we bridge the gaps, while ensuring that the crisis brought by Covid is turned into an opportunity for bringing in the changes that our education system has long needed? Four experts from the field discuss the problems and prospects of education in the post-pandemic scenario.

Imagining The Post-Pandemic Campus

Do we merely restore the old? Or do we use the present disruptive phase creatively, to re-examine the fundamentals? India’s top educators weigh in on the key issues.

Will Indian education ever recover from the blow the pandemic has dealt?

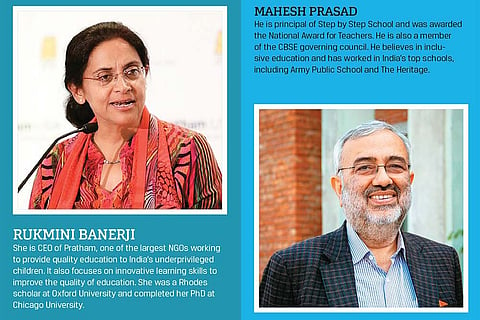

Rukmini Banerji: We are in an unprecedented situation, hence it is hard to predict what lies ahead. A lot will depend on what schools decide to do when they are able to open. For example, a study of the long-run impact of the Pakistan earthquake, by Jishnu Das and colleagues, found that most social indicators returned to their previous levels in a few years. However, children’s learning levels did not. The authors attributed this persistent deficit to the fact that schools returned immediately to grade-level curriculum in order to quickly cover lost ground. Once schools open, an important part of recovery will be to allow children and teachers time to reconnect and settle down. The focus for at least the next few months needs to be on building/rebuilding foundational skills like reading and basic arithmetic. Data shows that even in pre-Covid times, a large proportion of children were well behind their grade level. Prolonged school closures may have worsened the situation. If priority is given to building foundational skills, it will give all children, especially the worst affected, the opportunity to catch up. If schools, especially primary schools, can devote the 2021-22 school year to building foundations and catching up, we may come out of this crisis stronger than when we went in.

ALSO READ: Give Me Back My Classroom

Mahesh Prasad: The pandemic has impacted education adversely in terms of loss of real-time human contact—the crux of all meaningful interaction and learning. Reports indicate a rise in the number of dropouts, especially girls, in government schools, as midday meal schemes, perhaps, acted as an incentive to go to school. Yet, while the pandemic has been challenging for students, teachers, parents and the school system, it has made us sit back and reflect on what’s worth teaching and how we want our children to be educated. This will help us realign ourselves better. And the loss can possibly be overcome with careful thinking, strategising and planning.

Mamta Saikia: The situation seems daunting. A lot that was achieved over the years needs to be rebuilt. Most of the head teachers, principals and teachers of our rural schools are optimistic about the future. While they are aware of students who have been left behind due to lack of smart-phones or other devices, they also believe that when students return to schools, most would have double engines supporting them—teachers in classrooms and apps in their phones. Students have also become pro-active and independent to an extent in exploring and learning, which will make them learn faster and catch up on what they have lost. No doubt it will take more than an academic year for all children to bridge the gaps in learning and skills such as communication, leadership and group-work. Those who did not have a smart device through this period will require special attention. The first challenge would be to make sure all children come back to school. Another critical component is to empower our teachers and school-leaders with training on blended learning, innovative teaching-learning material, technology-support, hand-holding and flexibility.

ALSO READ: Flight To The Future

Dinesh Singh: At the best of times, the education scene has not been very encouraging. The pandemic has certainly not helped, but it could not have made it much worse. Indian education has been mostly stagnant for some years now. The pandemic has severely disrupted the regular in-person blackboard-based classroom teaching, caused much disruption to delivery processes. But was the traditional mode of teaching really delivering what was truly needed? The traditional pedagogy in most of India’s schools and colleges was causing more harm than good. Certainly, we have lost much due to the pandemic as schools and colleges have been functioning in a haphazard manner, with little long-term clarity on the way ahead. The other major loss is that we did not develop a pedagogical strategy for technology-based digital learning. No institution seems to have produced a practical pathway for using this opportunity to develop and take advantage of online and IT-based learning processes. Governments seem to be just as lackadaisical in this arena. This has been harmful, as a golden opportunity was not availed of.

ALSO READ: The Interruption As Window of Opportunity

What is the way ahead? What are the fundamental changes that we need?

Rukmini Banerji: The New Education Policy 2020 lays out a clear roadmap at least for the elementary stage. Structurally, it outlines stages of education rather than grades. The first stage from pre-school to standard 2 is the foundational stage during which the focus has to be on building a strong foundation and exposure to a breadth of skills. Rather than focus on grade-by-grade curricular expectations, the stage allows for a continuum approach and an opportunity to acquire a set of foundational skills by the end of this stage. Up to now, for a variety of reasons, many children fall behind in early grades. Starting well is essential if a child has to navigate successfully through the education system as s/he gets older. A significant proportion of today’s school-age children have parents who have not had much education themselves. While such parents support children’s schooling, they often feel ill-equipped to engage in their children’s learning. The partnership of parents and children is key to young children’s growth and development.

Mahesh Prasad: Rethinking and realigning our education system is the need of the hour. Fundamental changes are long overdue, and the pandemic has made them more urgent. We must learn from the example of mature democracies and strengthen our public education system. Public-private partnerships have to be built systemically, with accountability and responsiveness as core principles. All fundamental change and choice will become rather clear if we answer the basic question—what is the aim of education?—with honesty and foresight. State-people partnership is the way ahead, and education needs to become a priority for the country if we want to deepen our democracy by creating level playing fields for all to grow.

Mamta Saikia: Building on the perspective from our rural schools, a few key things have happened on the ground: (i) technology and its use has been accepted not only by teachers, but students and parents as well; (ii) parents have become a lot more aware and involved in their children’s education irrespective of their literacy levels; (iii) students are using phone-based apps to discover learning; (iv) a large section of students has been left behind due to lack of smart devices and they need special attention when they return to schools; (v) many students may not return to school unless concerted efforts are made; and (vi) learning gaps exist among students due to Covid-related school closures. The immediate future would see partial opening of schools—blended learning with a combination of at-home and in-school studying, synchronous and asynchronous learning. Teachers, school-leaders and education administrators have to be empowered to be creative and flexible as per local needs because different areas may experience the Covid impact differently. We need to build on technology-acceptance, especially in rural areas, and equip our educators with the necessary skills and content. Creating village-based device banks or libraries for the provision of devices to all students and upgrading technology infrastructure in schools would be key to building an education system that can withstand situations like Covid. We will need to bring all our children back into schools with concentrated efforts, and create programmes to ensure children’s mental well-being and safety as well as for bridging the learning gaps.

Dinesh Singh: It is necessary that we make the curriculum meaningful by teaching a little less and by making the learning processes more interactive, with a transdisciplinary approach. We also need to de-emphasise the blackboard-lecturing-rote learning approach. Examination processes and ideas need to be radically overhauled. We need to adopt a problem-solving approach to learning where greater freedom is given to students to work in groups, to explore and be creative. As an illustration, the age-old practice of mechanically analysing chemical salts as a part of the chemistry curriculum in schools and colleges could be made far more productive by posing challenges such as analysing salts, bacteria, viruses and fungi from soil and water samples. The important thing is not so much the answer to all problems as the methods and ideas adopted to arrive at solutions. The use of technology and the Internet should become fundamental. The Internet and its myriad platforms offer enormous scope for creating learning platforms. YouTube houses enormous knowledge. Of course, there is also a great deal of dubious stuff. The process of sifting the grain from the chaff on YouTube and other such platforms is a great learning process for teachers and students. Learning should be made more student-driven and project-based. The spirit of entrepreneurship needs to be embedded in the curriculum.

Do online classes democratise education or does the digital divide sharpen inequalities?

Rukmini Banerji: During the pandemic, online classes have been a feature only for a very small section of the school-going population. It has been difficult for most others to be connected in a continuous way to the instructional process. If digital methods are going to become a permanent feature of children’s educational life, then strong efforts will have to be made to ensure equitable digital access (devices, connectivity) and to build digital capability for embedding teaching-learning processes that benefit all children.

Mahesh Prasad: In a country as diverse as ours, such questions are multi-layered and can pan out in various ways in different contexts. In some cases, we have observed that online classes give voice to students who would otherwise find it difficult to participate fully in whole group offline settings. On the other hand, economic inequalities, lack of access to appropriate technology and skilled teachers, have hindered learning. However, advancement in technology and its availability at a lower price in future can help eliminate the digital divide. Easy access to knowledge and information to many will soon be a reality. The pandemic has indeed opened possibilities to democratise education; however, its success will depend on the choices we make with respect to the education system and will require strong political will to carry it forward.

Mamta Saikia: Experience in rural India with respect to use of technology in education was varied. It is rarely about availability of laptops or computers at home. In most cases, if technology is supporting children, it is a smart-phone. Most of the teaching-learning happened in the initial months of Covid by sharing content, online links, videos over Whatsapp, followed by calls by teachers. Gradually teachers who mastered the online tools moved to online classes as well. Education apps and links/material sent by teachers were timely support to students. It has only been due to the commitment of teachers and school-leaders that students stay engaged with studies, to the extent possible, in these difficult circumstances. It may not be uniform across schools and students without smart-phones would need tremendous support to bridge the learning gaps when they go back to schools. One benefit of technology is that students are exploring apps and online content, which is allowing them to take charge of their studies, especially in higher classes. For junior classes, where teachers have involved parents as partners, we are seeing parents playing an active role in their children’s studies. This, coupled with ensuring availability of devices for all children and strengthening schools’ tech infrastructure, will be a move towards bridging the gap.

Dinesh Singh: Online classes and learning can democratise education provided the right infrastructure and access is made available to institutions and individual learners. In my many years of experimentation, I found that I obtained fabulous results even with basic technology and the right pedagogical practices. For instance, in 1992, I had lectured to class 12 students on calculus through live television for six days. The teaching was interactive in a rudimentary manner. The response was phenomenal even with such a bare bones use of technology. Later, we used better infrastructure and facilities at Delhi University and student productivity shot up. This was made available to all students and faculty. If done in a fair and transparent manner, it leads to democratisation. The mistake most teachers committed during this pandemic was to have mechanically reproduced rote classroom learning for online learning. Classroom learning in most schools and colleges was counterproductive to begin with. Good pedagogies and practices for online learning need to be put in place. If this is not done, then online learning can be harmful and leave behind most students.

What psychological impact would the last two years have on students?

Rukmini Banerji: If you ask anyone about their school and college days, the strongest memories are of friends and of activities they did together. Most memories are of what happened in the canteen, corridor, playing field or elsewhere on campus. Social bonds are made, and social skills to interact with a diverse range of people and situations are acquired during our school and college days. Older children would have been able to sustain some of their prior friendship networks. But, for younger children, memory of school is faint and forgotten, or they did not have a chance to go to school before Covid. When schools open, especially young children must be given time to connect with each other, learn how to relate with situations outside the family context, and be able to articulate and share their experiences from the prolonged and often tense times of the pandemic.

Mahesh Prasad: Learning happens best in diverse social settings. The past two years have impacted this essence on which schooling is based. Being isolated from peers and teachers, and sitting in front of a screen for hours, have left scars on the student’s life. The human mind and body are not designed for such a passive lifestyle, and the ill-effects have begun showing up. Students are dealing with isolation, loneliness and gadget addiction. Also, many are struggling to follow a consistent routine, which is essential to bring in some sense of stability. The morbid coverage of the pandemic in the media and close encounters with the pandemic within families and among friends have left indelible marks on their lives.

Mamta Saikia: Three aspects are worrying educators. First is the potential impact of the fear about Covid. Training teachers to enable them to conduct joyful classes for students and motivational sessions with counsellors are required. Secondly, the habit of coming to school regularly, the discipline and structure of a school, would have to be worked upon as students have been at home for so many months. The exposure students get at school has been missing for months. Teachers worry about the loss of basic skills as communication, leadership, ability to work in teams etc among students. A concerted effort will have to be made to ensure that the benefits of in-school activities keep pace with education as these build critical life skills.

Dinesh Singh: The long-term harmful effects of the pandemic on children will take time to be assessed. However, our institutions that manage schools, colleges and universities have been quite clueless on how to alleviate the stress on students. The complete confusion on examination processes and timings as also last minute decisions have added to the stress. Parents, especially middle-class parents, have also collectively contributed to causing harm. It would have really helped if the central and state governments had approached the issue with a long-term and early decision.

How do you foresee the future of education, from kindergarten to professional colleges?

Rukmini Banerji: Take a blank piece of paper. To depict pre-Covid times, sketch two outlines at opposite ends of the sheet—one called “home” and the other called “school”. The role of “home” was to send children to school and the role of “school” was to teach children. In the pandemic, the empty space between the two institutions got filled up. The “who”, “where” and “how” of learning changed: different kinds of people (parents, siblings, neighbours and others), variety of mechanisms (face to face, digital, radio, TV, books and materials), different organisational modes (mixed groups working together, individual study). But perhaps, most importantly, the “what” of learning has also undergone substantial transformation—both due to the “push” of current conditions and context, and the “pull” of children’s choice and curiosity. As we recover and rebuild our education systems, these fundamentals shifts must be recognised and incorporated. A crisis cannot be wasted. It is imperative that we emerge out of it stronger, better equipped and more relevant.

Mahesh Prasad: The pandemic has made us realise the fragility of human life. This has made many of us pause and reflect on the current system of education and the way we lead our lives. The future of education as I envision it is one that helps us create sustainable systems based on compassion and mindfulness. From kindergarten to professional colleges, social, emotional and ethical learning should find their rightful place. The blended way of learning is here to stay, and choices regarding these have to be carefully thought through to make it seamless for the benefit of all concerned. And the way the synthesis between technology and real-time contact plays out will be of utmost importance. Most importantly, we need to humanise education at all levels for the collective survival of humankind.

Mamta Saikia: While institutions will continue to be at the centre of education design, how education will get delivered would change fundamentally. In the coming months, blended learning models will have to become the norm. Educators will have to be empowered with training, relevant teaching-learning resources, and technology for in-school, at-home, synchronous and asynchronous teaching. A core theme across schools would be to make up for the learning loss, building life-skills and ensuring all students, especially girls, return to school. Role of technology will have to be strengthened not only in teaching-learning and assessments, but also in administrative processes. Flexibility and empowerment of education leaders on the ground would be key to successful operations in these times, as decisions would have to be made locally depending on the Covid situation, local realities and needs of the children.

Dinesh Singh: In the years ahead, India will need to overhaul its education system for schools and colleges. We need to ensure that our students have real-world skills, and are connected through our learning and educational systems and institutions to real-world and social challenges and needs. Technology and self-learning will become more and more important, and the regular learning models in existence will recede a fair bit. The university of the future will be more virtual and less campus-based. Peer learning will take a central place. The world around us will become more and more a learning system or a living university. Each and every worthwhile real-world experience will begin to find accreditation. The place of a university degree will diminish and specialised certification will gain more importance. Of course, campuses will thrive, but their role and practices will change. A coffee shop and a neighbourhood too could evolve into a sort of campus. Libraries will change radically as they become more and more virtual. Most importantly, a university can be deemed to be a university of the future if those who pass through its portals have become adept at engendering solutions to the problems that beset society. So, all universities have no choice but to be universities of the future. It is thus useful to try and identify the challenges and goals looming over the horizon, and use them as a collective touchstone and compass when dealing with the idea of a university of the future. Such a listing will necessarily include artificial intelligence, robotics, big data, climate change, environmental degradation, disease prevention, public transportation, national security, engendering the wellbeing of the rural population, slum redevelopment and so on.

Tags