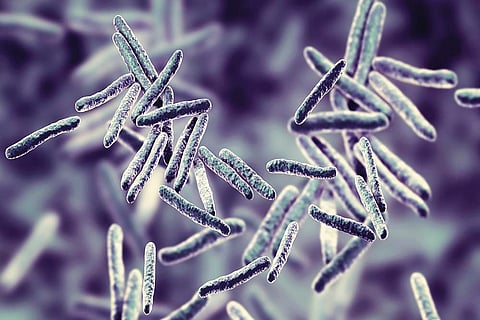

The “little flu” took the spotlight with a Usain-like bolt and conquered the planet in one (un)forgettable year. Signs are ominous it will keep its podium and headline spots through several seasons to come. Covid is the Sergei Bubka of the microbial Olympics—upping its record a notch at a time. On a parallel track and away from the fuss, an ancient shadowy marathoner is continuing to amass its morbid medallions—if death can be called medals, a macabre metaphor. Tuberculosis, aka TB, is a formidable ace of the long distance; a disease that has plagued humans for more than a millennium. Mycobacterium tuberculosis—the bacterium that causes TB—kills 1,200 people daily in India, says the World Health Organization.

Need Lungs To Choke TB

Tuberculosis kills 1,200 a day in India, but there’s no urgency to eradicate this contagious disease that plagues poor nations

The nation leads the global caseload of TB. Yet, it is something people try to avoid talking about. Why? Why is it not the fearsome disease that people dreaded three decades ago? Where has that wracking, back-bending, blood-spitting TB cough gone from our collective consciousness, from our films, from our pulp fiction? Why it’s not a trending topic on our Twitters and Facebooks? Wasn’t TB the chronic villain of our films of a certain vintage? Did you notice Devdas of Devdas didn’t drink himself to death? TB killed him. Poverty and TB were the incurable shadows that stalked Sanjeev Kumar in Parichay (1972)—a prophetic image symbolic of what this killer bacterium would become this century, “a poor man’s disease of the third world”. That answers why TB has gone under the radar, and not in a good way.

Tuberculosis has gone down in history as one of the oldest diseases afflicting mankind—an ancestor of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis arrived on the scene more than 150 million years ago. TB killed one of seven people in the US during the 18th century, but the disease was eradicated in the developed West through elimination of poverty, improvement of nutrition and living conditions, and by isolating patients in sanitariums built off the concept of quarantine. Fresh air, a dry climate, outdoor exercises helped accelerate the healing process. For the context, this is why Dewas in Madhya Pradesh and Kumar Gandharva are linked. The classical vocalist made Dewas his home and its dry air healed him back to singing fit, despite losing a lung to TB. The arrival of the antibiotic streptomycin, the Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine and new, effective drugs made the disease treatable, curable, and preventable. But TB continued to thrive in the “underdeveloped” world. Like those twilight-year European league footballers playing in the Indian derby—and with deadly efficiency.

The WHO estimated 10 million new global TB cases in 2017, along with 1.6 million deaths, mostly in developing countries with poor health and socioeconomic infrastructures. The bulk of the burden falls on India, where factors such as poverty, poor diet, overcrowding and pollution kept TB ticking—hiding and resurfacing at ease. In fact, it has become more complex, more resistant to drugs. It has been a recurring allegation that the West has turned its back on the poorer nations in their fight against TB. “Tuberculosis doesn’t bother the US and West European countries because it is a disease prevalent in poor and developing nations like India,” says Dr Ishwar Gilada, president, AIDS Society of India.

Health experts say TB needs as much attention and surveillance as COVID-19 and they fear that the single-point focus on the virus could give the bacteria a free run in India, which will have deadly consequences on the population. “Since Covid has badly affected the Western countries, the media there reported the disease extensively, which is why awareness around it is a lot more. Another reason is that Covid has affected a lot of people in a very short span of time. Therefore, it is has gained more prominence than TB.” The coronavirus has killed more than 3 million people worldwide since it was first detected in China in late 2019. The number of lives lost is about equal to the population of Kanpur, Lucknow, Jaipur, Pune, and Nagpur.

The total number of TB infections and deaths could be much higher in India than what data suggests because the Union health ministry’s National Tuberculosis Elimination Programme (NTEP) doesn’t track and trace new occurrences as actively as it does for Covid. “The online tracking mechanism in TB registers only those patients who come to hospitals on their own and are diagnosed with the disease. There is a system of contact tracing in TB, but it has to be more strengthened and stringent…like they do for Covid,” says Dr Neha Rastogi Panda, infectious disease expert at Fortis Hospital, Gurgaon. There are red flags everywhere. India’s TB report for 2020 says 2.4 million patients were detected in 2019, but only 80 per cent received successful treatment.

Tuberculosis is far more contagious than SARS-Cov-2, the virus that causes Covid. A Covid-infected person can transmit the virus to less than two persons, according to latest research. TB can infect more than four, says Dr Sonam Solanki, a pulmonologist. But TB has existed for far longer than Covid, and making comparisons in terms of cases and mortality is not equivalent.

A bacterium causes tuberculosis, while a virus genetically related to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus causes COVID-19. Both are spread through close physical contact. When a tuberculosis-infected individual coughs, Mycobacterium tuberculosis can remain suspended in the air longer, until it’s inhaled by someone else, usually in a confined space.

The body’s immune reaction to the pathogens also differs. Tuberculosis basically puts a little ‘bunker’ inside your lung and hangs out there until you have a weakness in the immune system. Say you get HIV, start steroids or cancer therapy. In those weak moments, the bacteria emerge from the bunker and infect the rest of your lungs. Once activated, tuberculosis does not stay in the lungs—it can infect the central nervous system, which includes the brain, muscles, skin, liver, lymph nodes and reproductive organs. Tuberculosis can persist in the body for up to 30 years.

Unlike Covid, treatment in TB prolongs for months and years and there have been umpteen latent cases, where bacterium goes into hiding after treatment and resurfaces when the person’s immunity level falls. This happens because the pathogen becomes drug-resistant following repeated use of the same medicines. Big pharma business interests and their attack-dog policies are blamed for resisting research and development of new drugs. TB affects poor people and they cannot afford expensive medicines. Besides, TB medicine prices are hugely regulated in India. “Only two new drugs were developed over the past two decades. Bedaquiline and Delamanid,” says Dr Gilada. The BCG vaccine, developed 80 years ago, has an efficacy rate of less than 40 per cent. For a new shot for TB, Gilada wonders if the world would ever show the urgency it showed for the Covid vaccines.

The reasons why tuberculosis flourishes in India are many, but the one that stands out is poverty—the primal source of diseases. Give this predator a chink, it will jump the picket, invade the shielded other side. No one’s safe; not even celluloid stars. It caught up with Amitabh Bachchan too, and he said in 2014 that he fought a painful bout of TB.

***

Mohammad Janipasha

49, Telangana

His TB returned after 32 years, dug a big hole in his lung

Mohammad Janipasha was diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis when he was 17. No one in the family had the disease and it was difficult for to figure out how he got it. “I was treated and recovered fully,” says Janipasha, a farmer in Bhadradri Kothagudem district of Telangana. As it happens with tuberculosis, the sneaky bacterium was hiding inside him, waiting to strike again 32 years later. The symptoms were tell-tale—Janipasha had mild fever, lost his appetite and started shedding weight. His condition deteriorated; the teetotaler coughed blood.

His doctor says he has a “big cavity” in his lung. “Investigation showed his TB has resurfaced. He is getting treatment,” says Dr Viswesvaran Balasubramaniam, consultant, interventional pulmonology and sleep medicine, Yashoda Hospital. He explains that TB can be broadly classified as pulmonary and extrapulmonary. “While the first one affects only the lungs, the latter can infect all organs. Janipasha was lucky that he was admitted on time and his disease was diagnosed early. Many patients lose the battle because of lack of early treatment and awareness.”

Suman Sharma

45, Jharkhand

Her brain TB was a ‘veggie worm in the head’ for some doctors

A nagging, throbbing migraine-like headache came to haunt homemaker Suman Sharma when she was 30. The headache became frequent and she couldn’t cope anymore. Physicians near home at Deoghar district in Jharkhand couldn’t help either. She went to Patna, consulted a couple of senior doctors and an MRI test was done. “The neurologists in Patna looked at my report and said I have worms in my brain,” Sharma recalls. “They said raw vegetables contain bugs and these enter the body when we eat infested veggies. The insects travel to the brain and cause problems.”

Doctors put her on strong antibiotics for several months. Her headache didn’t go away. Instead, the pain got more intense. She would lose consciousness. Her vision dipped too. “I went to Delhi and got admitted to AIIMS. They found brain TB,” she says. Medication showed favourable signs as the first few doses started giving her relief. “I was discharged after a few days, but I remained on medication for several months. I am fully recovered now,” she says.