Dear Reader,

The Wandering Needle

Every day this past week, about 25 million people across the globe received a Covid vaccine dose. That’s about 300 jabs every second. Read all about our race against mass deaths.

What shall we call you? Vaccinee? Would-be vaccinee? Or is there another, more elegant word for one who receives, or is set to receive, a shot that will teflon-coat you against the more perverse effects of the Sars-Cov-2 virus? Whatever be the lexicological side-effects of the pandemic, this following story is for you. Consider this vast, rippling canvas: every day this past week, about 25 million people across the globe received a Covid vaccine dose. Slow down that time-lapse picture by a few frames—that’s a little over a million folks getting a shot every hour. Or, just a little less than 300 jabs every second.

Or, think of it spatially—we’re talking of a population not quite the size of Delhi, but equal to the whole of Australia.

ALSO READ: In Small Doses

Then, zoom in on the Indian landmass itself. Vaccinating a billion, and then toss in a few tens of millions for loose change—that’s the grand challenge we are up against, again, measured in hours and days. Every day this past week, over 2 million people were registering on CoWIN for their shots—roughly about the same number of Covishield and Covaxin doses that India produces daily. All of them frantically looking for appointments to open up. But given that supply is short, they will have to wait until the priority groups are first covered. In our big cities, people are queuing up for tokens outside vaccination centres every morning—for that luck of the draw.

But pan out and then zoom in again: to the remote reaches of the expanse before us. What’s happening there? We bring you some of those stories—from the hamlets beyond those frozen cliff faces of the Himalayas where the internet doesn’t reach; the Adivasi habitations deep in the jungles of the Western Ghats; the sandy expanses of Rajasthan; the swamps of the Sunderbans; the hilly tracts of central India. Those blue boxes carrying vials have to reach every nook and cranny, often by the sheer grit of the small teams of nameless vaccinators that are, even as we speak, gearing up for an arduous trek, a treacherous road journey or a safe passage through a conflict zone.

ALSO READ: Finding Family In Time Of Pandemic

Reaching is only half the battle won. Reaching out is another story. Even vaccinators in our urban jungles can testify to that. Surprising as it may seem, the success rate in some remote corners of India outpaced many small towns in the plains even when vaccine supply wasn’t choked. Hence, the route to vaccine coverage is via awareness campaigns and transparent communication, besides, of course, vaccine availability.

That latter part is a worldwide struggle at the moment. But India finds itself in an ironic situation on more than one count—a vaccine powerhouse whose campaign is now slowing down for want of vaccine doses. The country’s daily run is still neck and neck with the US (where too the pace has slackened of late). But look at the population coverage and the gap widens instantly: 60 per cent of all adults in the US have received at least one dose. India will have to run much faster to get anywhere close to that threshold of relative safety. Along that dizzy path, sooner rather than later, we hope you cross that line.

Thank you

Blessed By The Dalai Lama, The Highest Motorable Village

Spiti is a spitting image of Tibet—its way of life, Buddhism, history and an out-of-the-world landscape that takes the breath away. And one can be truly short of breath in Komic, a signpost of the real Spiti in northern Himachal Pradesh, sequestered from the rat-race world by a Himalayan terrain that spits danger at every bend of the mountainside, non-tarred roads, the jaggedly stones cleaving off tyre treads in no time. At 15,027 feet, the village of Komic has the highest motorable road. Everything is sparse here…even oxygen in its air. Supply trucks bring everything else. Winters are snowed out. One of the recent sorties brought a consignment that the residents were not willing to accept. It’s a blue box containing vials of a vaccine for Covid. And then a miracle happened. “There was a bit of reluctance initially because of rumours of side-effects. Then the news came that the Dalai Lama has driven down to a vaccination centre in Dharamshala for inoculation,” says Gian Sagar Negi, additional deputy commissioner. The Dalai Lama’s endorsement worked wonders in Spiti, the snow-clad region almost 500 km from Shimla. The vaccination coverage was almost 96 per cent. In Komic, most eligible men and women turned up at a camp on April 15. The team of vaccinator Prem Singh, ASHA worker Padma and verifier Kulwant inoculated 55 people. On May 20, the village achieved 100 per cent vaccination of residents above 44 years.

Komic’s closest neighbour is Hikkim, and at 14,400 feet has the highest post office and had the highest polling booth too until Tashigang village (15,256 feet) took over that honour. The three-member vaccine team covered Hikkim as well before they returned to Kaza, the nearest township, half-a-day’s ride away. They worked under hostile conditions—subzero temperature, heavy snowfall and rain. The villagers cooked for them, fed them well. The womenfolk took the initiative. “Our monks and scholars at monasteries also volunteered,” says Soman Dolma, panchayat pradhan at Kaza.

Like much of Spiti, both villages remain isolated from the rest of Himachal for six-seven months every year because of the snow on the mountain passes—especially Kunzum La at 14,931 feet. The sole access, after April, is from Kinnaur district. “People think the Rohtang tunnel will close the divide. That Spiti is now connected with all-weather roads. That’s not true,” says Negi. The vaccine delivery is a logistical test—the stock is ferried from Shimla via cold chain to Kinnaur and then to Kaza. One of the vaccination centres was at Geu village, where 28 of its 116 residents tested positive for the coronavirus last November.

—Ashwani Sharma

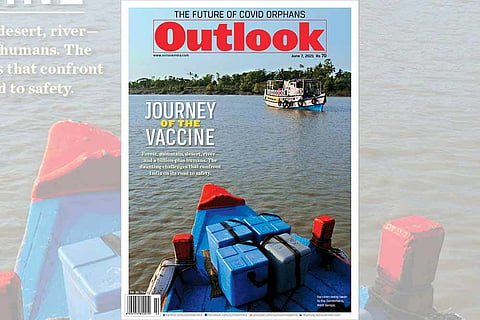

The Blue Box By Boat, By Bicycle

The land—or rather the water—dictates life here in the Sunderbans. A colossal swathe of mangrove swamps, brackish water channels, islands, hardworking/hard-saddled people, tigers (the only ones on the planet that swim), crocodiles…it’s as mystifying as Bon Bibi, the forest spirit of the Hindus and Muslims alike. And as darkness descends, shushing mothers keep the legends and myths alive. Dark clouds are plentiful here—but a new, darker demon threatens the people. Covid. They need a silver bullet and it comes to them in blue, squarish plastic boxes; like ice coolers the well-heeled carry to their shindigs. The precious cargo travels by boat—often a single-engine, smoke-belching, canoe-like ferry. These life-savers go deep into this astonishing outer-world within our world—100 km or more from Calcutta, via the link outpost called Gosaba on the edge of the delta.

Rabindranath Mondal, 51, has been doing what his illustrious namesake once said: “Ekla chalo!” Walk alone. He wakes up at dawn, hurries to the Gosaba hospital—a storage and distribution point for Covid vaccines—and rushes out on his bicycle to Chotomollakhali rural hospital, about 2.5 hours away. He takes two ferries on the way, carrying a life-saving payload strapped to the back carrier of his bicycle, and balanced precariously on swaying boats. He bicycles through dirt roads—a non-stop journey in heat and humidity that saps every fluid from his body. Villagers offer the vaccine carrier water, but on such a desolate landscape it’s hard to come across people. Even if he does, there’s always the fear of getting infected or infecting someone. On his way back, he waits several hours to board a ferry. The service has been affected by the lockdown. Yet, Mondal travels 12 days a month.

The Sunderbans has 14 gram panchayats and a vaccination target of around 200 people a day in 21 centres. Unlike places that have reported vaccine hesitancy, the people here are keen to get a shot and they line up early—often leaving bags, bottles and brollies to mark their place in the queue—at inoculation centres, says doctor Indranil Bargi. Those who fight death every day pick out instinctively what’s best for survival.

—Text and photos: Sandipan Chatterjee

First The Mask, Now The Shot

The soil is moist. It’s tropical jungle undergrowth after all—there are leeches on your feet. And the air is thick with peppery herbal perfumery. But it’s also surprisingly, bracingly, cool on the skin. Kerala? Well, yes. Attappadi can loom upward to 5,500 feet from sea level—that’s Gangtok’s elevation. That air is also about the purest you can hope to breathe. No wonder Akbar Ali faced those incredulous stares from the Adivasis when he landed up there last February—that is, in 2020, when the pandemic was still new, but Kerala was trying to cover all bases. A social worker with the tribal department in Wayanad district, he had set out for a routine visit to one of the Adivasi settlements when he encountered many perplexed looks. Umpteen questions flew his way. All they wanted to know was, why had he covered his face with a mask?

That protocol was still new for pretty much the whole world those days. You couldn’t blame an Adivasi hamlet up in this neck of the woods—the high ranges where Kerala meets Tamil Nadu meets Karnataka. Ali was perhaps among the earliest Covid-era health evangelists in the world. The Adivasis listened intently to what he had to say about this ‘dangerous unknown virus’ and how to keep it at bay. The task wasn’t too arduous—he had been working here for the past seven years and had established a trusted channel of communication.

That outreach speaks across a real chasm, one that has persisted through Kerala’s modern history. Literacy (in Malayalam, needless to say) has flown upwards, but the rest of those famed social indices never quite reached those high ranges. And Wayanad has Kerala’s highest Adivasi population—over half of its total four lakh. The only time Attappadi made the news, it was for starvation—regardless of the party in power.

Some of that infamy has had its effect. Now Wayanad is top priority for the state’s Covid immunisation programme. The tribes in these hills include the Paniya, Kuruma, Kattunayakan, Adiya and Kurichiya—the latter made famous by their alliance with Pazhassi Raja, who fought one of the first guerrilla battles against the East India Company. Tribes like the Kattunayakan and Cholanayakan live in the deep forests, but there’s a rapport. “We visit them once a week. They don’t interact much with outsiders, but they trust us. They call us for any help. It’s a misconception that Adivasis are against vaccines. They understand the grave nature of the disease,” says Ali. Community radios and Hamlet Ashas—educated representatives from every colony—played a key role there. Besides, the Adivasis here are no strangers to immunisation. “Children are vaccinated regularly in PHCs,” says Ali.

When the Covid vaccination programme rolled out, the elderly were covered first in a special drive. The tribal department, the district collector, social workers and many arms of the administration were at hand to ensure 12,000 people above 60 were vaccinated in the first phase, says Dr Shijin John, district nodal officer. Yes, 12,000 out of 13,000 Adivasis aged over 60. “We did it in two days,” says Dr John. Shortages have now hit the programme. “We are now looking to inoculate the 45-59 age segment,” he says—preference is for those awaiting second doses.

Suspicion about what the mainstream may impose on them is natural for the Adivasis. They are hesitant to venture out of their hamlets. Hubs created around nearby primary health centres and schools helped—even those in the deep forests were happy to be ferried there. “We make them comfortable. After vaccination, we made them sit for an hour, then dropped them back,” says Ali. Vaccine hesitancy was a reality. “But we convinced them,” says social worker V. Sindhu. The first wave hadn’t hit the Adivasis too bad, but the second wave spike saw a 24/7 tribal COVID-19 cell being set up. “Nine tribal mobile medical units are on the job,” says John. A slender population, but profoundly Indian, is at stake.

—Preetha Nair

‘Don’t Want To Take The Jab And Die’

The Mushahari Community Health Centre is barely 10 km from Muzaffarpur, the commercial capital of Bihar. It’s not a remote area either, located as it is along the Muzaffarpur-Samastipur highway. But the locals are wary of vaccination. In the 16 rural panchayats under this block, very few people are coming out to get the jabs. There’s widespread illiteracy and lack of accurate information. Curiously, many educated persons are also hesitant to take the jab.

“There is a lot of misinformation and superstition about the vaccine among the people. We are trying to make them aware,” says Dr Rajesh Kumar, block medical officer. In Taraura Gopalpur panchayat, less than 2 per cent of the 7,000 voters have been vaccinated. Around 70 per cent of them are from the backward sections. “Neither is the government doing the job of creating awareness properly nor do the people have the right information,” says Aftab Allam, the sarpanch. “Many people think they will die or fall sick if they take the vaccine. The death of a few people reportedly after taking the vaccine has added to their fears.” According to Dr Kumar, only a few cases have been reported of someone dying after vaccination.

When asked why she had not taken the vaccine, a local woman says, “I have six children. If I die after getting the vaccine, who will take care of them? If the Nitish Kumar government gives me a compensation of Rs 4 lakh beforehand, then maybe I will get vaccinated.” Putul Devi, a member of Ward No. 15, says, “We are telling people that the vaccines are safe and have no side-effects, and that they will protect them from coronavirus. But few are listening.”

At a health care centre in the adjoining Sherpur panchayat, a team led by pharmacist Manisha Kumari has vaccinated many villagers. “Educated people take the vaccine. But most people don’t want to take any dose. In fact, some of them changed their minds after waiting a couple of hours for their turn to get the vaccine,” says Kumari. “Since the vaccination of those above 18 years has started, more youngsters are coming forward. I hope the old and illiterate people will follow them in the days to come.”

It’s the same story in Manika Harikesh panchayat, around 3 km away. “The vaccine is made of coronavirus. If we get vaccinated, we might die of infection. We are healthy at the moment and do not need any vaccine,” says Bhola Singh, a 60-year-old villager. His children Sumit Singh (32) and Chandan Singh (35) nod in agreement. “Why should we take the vaccine? One of my relatives lost her life after being vaccinated. Many others have died too. It is not safe at all.”

—Neeraj Jha

7 Km On Foot In 41 Degree C

It’s not every day that 56-year-old Mangi Devi walks half a dozen kilometres or more in the searing desert heat. But this is the third such sortie in two weeks for Devi, a resident of Alamsar village in Rajasthan’s Barmer district—around 35 km from the India-Pakistan border. All for a jab of the Covid vaccine. As she trudged along the hard and coarse roads of Barmer, the traditional Rajasthani odhani draped over her head gives Mangi much needed relief in the arid climate, where the mercury soars beyond 41 degrees C.

Mangi is not alone. Three other women from her village had accompanied her to the primary health centre in Dhanav, a village nestled in the deep interior of Barmer’s sandy swathes. It took them two hours to reach the health care centre, some 12 km away from their village. “The third time was lucky for all of us,” says Mangi, a mother of three. “We used to leave at 7.30 am from our house, walking 6-7 km to the first bus stop and then taking a rickshaw. Twice, we had to return as there were no vaccines available. We were eager to get it done as soon as possible because most of our villagers were testing positive since the second week of April.”

The Dhanav vaccination centre caters to villages such as Alamsar, Burhankatala and Kundanpura Sava in a 20-km radius. While Mangi has taken her second jab and is feeling relieved, she is equally concerned about her children who are yet to receive their first dose. “I want my children to get the vaccination as soon as possible,” she says. “My son is a salesman at a local shop and my daughter walks a kilometre every day to the nearest tubewell to fill water pitchers for our home. Both are exposed to the environment and infection is spreading fast in the rural desert also. We contacted the nearest schoolteacher who visits our village on awareness campaigns. But he said that no slots are available in the desert districts for those below 44.”

This is the story of most rural people in Jaisalmer and Barmer districts of Rajasthan. While the elderly folk have received two shots of vaccination, the youngsters are yet to receive their first jab. Most of the centres are away from the villages and people have to walk several kilometres to reach one. In Rajasthan, as of May 8, about 1.1 crore people had received the first dose and 26 lakh their second dose.

As per the official health bulletin last week, so far 1.7 lakh people in the 45-60 age group have received the first dose in Barmer district and 10,525 have got the second. Similarly, in the 60-plus age group, 1.8 lakh people have received their first shot and 41,400 their second shot. However, slots are yet to open for those below 45 years. “We are running short of vaccination, which is why the drive has become slightly slow,” says Mohinder, chief health officer at Barmer. “We aim to vaccinate everyone. From next week onwards, we are hopeful to get designated centres for youngsters also.”

A booth-level officer, who is a local schoolteacher, has been assigned the duty of convincing people to take the jab. “We are trying every bit to make the rural population aware. We are receiving an overwhelming response, but the vaccine is in short supply,” he says.

—Tabeenah Anjum

Cover For A Fragile People

The last-mile connectivity to Thalamookkai, a tiny tribal village tucked away in the Nilgiris of Tamil Nadu, has to be on foot—on a mud trail through evergreen foliage so deep the sun seldom kisses the ground. Unseen dangers creep around: skin-burning nettles, prickly thorns, snakes, leeches, predators. Shod in sandals, three men from the district health department trod this path in Kotagiri taluk for the singular task of inoculating 12 eligible villagers against Covid. “All our tribal villages are small and scattered, which makes the coverage even more challenging,” says Innocent Divya, the district collector.

The tribal population of Nilgiris district is around 30,000, comprising six particularly vulnerable groups—Todas, Kotas, Irulas, Paniyas, Kattunayakas and Kurumbas. “Since their population is dwindling, the government is taking extra steps to protect and preserve these groups. They were initially unwilling to take the vaccines, but our health workers convinced them to give up their hesitancy. Tribal leaders, council members and NGOs helped too in persuading them to accept the vaccines,” Divya says.

The authorities have decided to vaccinate the entire population. The 18-plus population at 13,656 far outnumbers the 45-plus of 8,778. Given their low numbers, it was imperative to cover the entire population, Divya points out. Many villages are located on hilltops and vehicles cannot make it there. The officials trek the last mile or two. “Well, that gives us exercise and fresh air,” quips a health official.

—G.C. Shekhar

Fluctuating Stocks...A Fresh Batch

The health centre at Amarpur, a small village nestled in the hilly Sihawal tehsil along the Madhya Pradesh-Uttar Pradesh border, came alive this Monday. A fresh batch of 1,000 Covaxin doses had just arrived at the vaccination centre, the first time since April when it ran out of shots.

The story of Amarpur village, with a large population of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, is perhaps symptomatic of what ails the vaccination drive in rural India, away from the glare of TV cameras. Until last week, the vaccination centre remained under lock and key on most days. Even though a doctor has been appointed as Medical Officer at the centre, there is hardly any activity even as the pandemic rages.

Many people who got their first dose of Covaxin are still awaiting their second jab, says local resident Jagjivan Cole. According to medical officer Aslam Ansari, vaccination was being done regularly, but it had to be stopped when supply dried up.

As of now, Madhya Pradesh ranks sixth in the country in terms of vaccination. The vaccine crisis started only in April when a rush for vaccination suddenly fuelled the demand for vaccines. The state government had launched the vaccination drive in inaccessible areas of the state, but vaccines are yet to make it beyond the tehsil headquarters at the moment.

—Shamsher Singh

Fear Of The Jab

Most people in Adivasi-dominated Jharkhand want to get inoculated as quickly as possible to protect themselves from the deadly coronavirus, which has killed lakhs of people in the country and beyond. As a result, the vaccine centres are usually overcrowded across the state despite the supply shortage. The remote Simdega district, however, presents an altogether different picture. A sense of fear prevails here. Even now, many people here prefer to look up a sorcerer when somebody falls sick than consult a qualified medical practitioner. This probably explains why there are no crowds outside the vaccine centres in the district, located along the borders of Odisha and Chhattisgarh. Until the end of the first round on May 8, only 26 per cent of the 45-plus target group had taken the first dose. As for the second dose, just 14 per cent took it—lowest in the state.

At the Jaldega block, 45 km from the district headquarters, more than 80 per cent of residents are from Adivasi communities. On May 7, health workers were waiting at the S.S. School vaccine centre for people to come and get their jabs. But only one person showed up. He could not receive his shot because at least 10 persons have to be in the queue to be vaccinated before a vial is opened. After a short wait, the solitary vaccine-seeker too left without being inoculated. The centre had to be closed when nobody turned up for the next two days.

Officials believe misconceptions are keeping people away from vaccine centres. There is a widespread belief that the vaccine causes sickness and even death. The district administration had launched an awareness campaign in January on the need to get the jabs at the earliest. It was also pointed out that 110 people had already taken the vaccines and that none of them suffered any adverse symptoms. But to no avail. Several villages are located in the remote hilly areas and it is difficult for administrative officials to reach there. To counter the misinformation, another awareness campaign has been launched among villagers with the help of MNREGA workers as well as personnel from the social welfare and education departments. Jaldega block development officer Vijay Rajesh Barla says people are hesitant to accept anything new easily. In fact, the Congress MLA from Kolebira, Naman Vixal Kongadi, too is yet to take a jab. He says he is keeping a watch on his health as he suffers from high blood pressure. “The recent death of former minister Neil Tirkey, who had taken both the doses, has sown seeds of doubt in the minds of people about the efficacy of the vaccines,” he adds. As some people did not follow Covid protocols after getting the jabs and died, villagers seem to have become wary of the vaccination drive.

—Navin Kumar Mishra

Mughal Road To Zoji La

With Covid deaths increasing every day in Jammu and Kashmir—on an average, the region witnesses 50 deaths daily—there are long queues outside health centres for vaccination. It’s a sign that the initial vaccination hesitancy has passed. But vaccines are in short supply. There are exceptions though. Like the remote tourist destination Sonmarg, on the foothills of Zoji La Pass, or Shopian district—the gateway of Mughal road in south Kashmir. According to health department officials in Shopian, about 90 per cent of the 45-plus age group has been covered, making it one of the top districts in Jammu and Kashmir for vaccine coverage.

“There was vaccine hesitancy at the initial stage in Shopian,” admits Dr Muhammad Yousuf, a block medical officer (BMO) in the district. “People had apprehensions that vaccination would make them infertile and it was tough to make them understand that it will not. We did a lot of counselling, and gradually they understood the benefits. I vaccinated myself first, before the health workers, and urged them to vaccinate themselves before the villagers. Health department workers would first visit the villages and people would turn up at the vaccination centres the next day.”

The drive hasn’t been easy, however, given the volatile backdrop. Shopian district has been in news for regular fierce encounters—of 37 militants killed by government forces in the Valley this year, 21 were in this district alone. Most of the 15 gunfights between government forces and militants in Kashmir this year took place in Shopian. Of the four south Kashmir districts, Shopian and Pulwama remain under prolonged Internet shutdowns and restrictions imposed by the government before and after cordon-and-search operations. Frequent encounters mean recurrent Internet shutdowns, making it difficult for the health department to upload vaccination data.

“Due to Internet shutdowns in the district, at times we had to wait five to six days to upload vaccination data,” says Dr Yousuf. Muhamad Khaliq, a health official, says they have come across instances in some remote villages where the date of birth on the Aadhaar card was fudged. “There were cases where the father was only three years older than his elder son, as per his Aadhaar card. This was bizarre, but we carried out the vaccination as per the date of birth on the card,” he says.

To the north, the last village in picturesque Sonmarg is Sarbali, beyond which lies the Zoji La Pass. According to Dr Nadeem Majeed, BMO of the area, health workers reached out to the villagers there soon after they returned from their annual migration. Due to heavy snowfall in the winters, Sonmarg closes down for six months and villagers move to the plains of Ganderbal. “To our surprise, they readily agreed after our health workers vaccinated themselves before them,” he says. The vaccination was carried out in schools and panchayat ghars. They also inoculated hoteliers and their staff, even some tourists who were in Sonmarg in early April. “We have achieved 100 per cent success in vaccination in the Sonmarg area,” Dr Majeed says. “It is because of the aggressive vaccination that you see fewer Covid cases here.”

—Naseer Ganai

On The Eastern Front

Dr H.S. Jongsom, in-charge of the health centre at Miao in Changlang district of Arunachal Pradesh, is sitting on 300 doses of the Covishield vaccine. The lot is meant for Vijoynagar, 157 km away by road and the easternmost inhabited place of the country, hemmed in on three sides by Myanmar. “I will have to get a chopper to send the vaccines to Vijoynagar,” Jongsom tells Outlook. While the jury is out on whether the coronavirus is airborne, the vaccine—at least in these parts—has to fly to reach beneficiaries.

That is easier said than done, though. There is a passenger service to Vijoynagar from Miao, the nearest town, but choppers can’t fly in rain, a near-constant companion here. “It has been raining continuously and in such weather I cannot hope to get a flight to send the vaccines,” Jongsom says. And more doses are expected soon. “I am keeping my fingers crossed,” he says. Sky One Airways and Global Vectra Helicorp Ltd are the two companies that operate the chopper service.

Jongsom had faced a similar predicament a couple of weeks ago when he had to keep watch over 200 doses of the precious vaccine for nearly a week before a Sky One chopper could finally take off with the load. There was only intermittent rain that time, unlike now, so the wait could be even longer. There is the 157-km road, of course, from Miao, but driving on it is a Herculean task—one accomplished by chief minister Pema Khandu, who had to trek many a mile through rugged, muddy terrain on stretches of the road through which his SUV could not carry any load. Khandu has promised a motorable road by March of next year. “The local people take three-four days to cover the distance on foot,” Jongsom says. “We will need more than a week.” Khandu, in fact, is the first CM to reach Vijoynagar since Arunachal Pradesh attained statehood in 1987.

In a population of about 5,000, so far just over 300 have received the first dose, says Changlang district deputy commissioner Dr Devansh Yadav. The process is under way to administer the second dose to those who are due for it and the 300 doses Jongsom is holding on to will cater to that, besides others who haven’t even had the first dose yet.

Vijoynagar is also yet to be listed for vaccination for the 18-44 age category. In fact, the drive for this age group started in Arunachal Pradesh only from May 17.

There are two centres for vaccination in Changlang district, one at the district headquarters by the same name and another at Miao. Same is the pattern in other districts of the state with each having two facilities. “Each centre has been allotted 100 doses for 10 days,” Jongsom says. “We are not sure when Vijoynagar’s turn will come. The government may bring in more areas under coverage later if we have enough vaccines.”

Vijoynagar has a community health centre where a doctor was posted in January. Storing the vaccine, says Yadav, is not a problem because a solar-powered cold storage facility is available. Fortunately, so far, no cases of Covid have been reported from the area. Jongsom says chopper passengers to Vijoynagar were being allowed only after being tested for Covid. “We are also trying to ensure that those who are taking the road are tested,” he says.

—Dipankar Roy

Ocean’s 99

Denis Giles, 45, is a journalist in Port Blair, the capital of Andaman & Nicobar Islands. He owns a local newspaper, Andaman Chronicle, and has been covering Covid since last year when the pandemic hit the island. Giles says that the vaccination drive was started in Andaman in late January and it has been extremely successful so far. “Initially, there was a little bit of hesitancy among some people, but over a period of time they realised the vaccine is the only way they can keep themselves and the island safe and secure,” says Giles, who took his first jab on April 12. His second shot is due on June 4.

Divided into three districts—South, North & Middle and Nicobar—the island groups’ total population is estimated to be 4 lakh, out of which 2.8 lakh are eligible for vaccination. According to Dr Avijit Roy, nodal officer for COVID-19, 99 per cent of the 45 and above group have got their first dose, and 17 per cent have received their second dose. “In the age group between 18 to 44, for which the vaccination drive started just a couple of days ago, there are 1,80,000 targeted beneficiaries and 1.4 per cent have been vaccinated by May 25,” Dr Roy says.

On the particularly vulnerable tribal group (PVTG) such as Jarawa, Onge and Sentinelese, Giles says the administration hasn’t made any official announcement about it. “We asked about the status of PVTG, but we are told that the government is contemplating it,” he says. Since the Great Andamanese, who also come under PVTG, have already intermingled with the common population, they have been vaccinated.

—Jeevan Prakash Sharma