Inglish As She's Spoke

In a world growing smaller and an India growing bigger, English is the currency of the future. Even insecure vernacular chauvinists can't deny us our due.

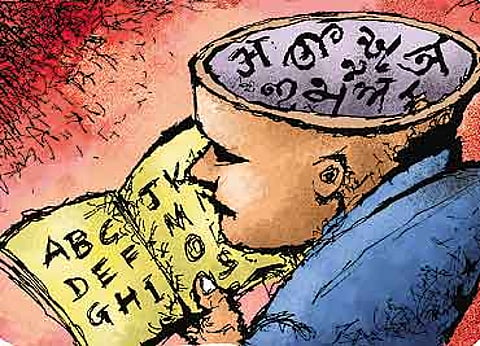

In Inglish, perhaps for the first time in our history, we may have found a language common to the masses and classes, acceptable to the South and North. We are used to thinking of India in dualisms—upper vs lower caste, urban vs rural, India vs Bharat—but the saddest divide, I always thought, is between those who know English and those "who are shut out" (the phrase of a deaf friend, Ursula Mistry, in Mumbai, who deeply feels the tragedy of those who can't participate). The exciting thing about Inglish is it may even unite Indians in the same way as cricket. We may thus be at a historic moment. One day, I expect, we will also find Inglish's Mark Twain, the writer who liberated Americans to write as they thought. Salman Rushdie gave Indians permission to write in English, but Midnight's Children is not written in Inglish, alas! And this is not surprising for the young Indian mind was not decolonised until the reforms of the 1990s.

What exactly is Inglish is not easy to define, and needs empirical research. Is its base English or our vernacular bhashas? If it's the latter, then it is similar to Franglais, the fashionable concoction of mostly French with English words thrown in that drives purists mad. Or is its support English, with an overlay of bhasha? I think it is both. For the upwardly mobile lower middle class, it is bhasha mixed with some English words, such as what my newsboy speaks: "Mein aaj busy hoon, kal bill doonga definitely." Or my bania's helper: "Voh mujhe avoid karti hai!" For the classes, on the other hand, the base is definitely English, as in: 'Hungry, kya?' or 'Careful yaar, voh dangerous hai!' The middle middle class seems to employ an equal combination, as in Zee News' evening bulletin, "Aaj Middle East mein peace ho gayi!" Three Hindi words and three of English.

In contrast to this vibrant new language, the old 'Indian English' of our headlines is an anachronism: 'Sleuth nabs man', 'Miscreants abscond', and 'Eve-teasers get away'. In the ultimate put-down, Professor Harish Trivedi of Delhi University contemptuously says, "Indian English? It's merely incorrect English." Inglish has parallels with Urdu, which became a naturalised subcontinental language and flourished mainly after the decline of Muslim rule. Originally, the camp argot of the country's Muslim conquerors, Urdu was forged from a combination of the conqueror's imported Farsi and local bhashas. As Urdu was transported to the Deccan, so is Inglish riding on the coat-tails of Bollywood across India.

So, is Inglish our "conquest of English" to use Rushdie's famous words? Or is it our journey to "conquer the world" as professor David Crystal, author of the Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language, puts it. He predicts that Indian English will become the most widely spoken variant based on India's likely economic success in the 21st century and the sheer population size. "If 100 million Indians pronounce an English word in a certain way," he says, "this is more than Britain's population—so, it's the only way to pronounce it." If British English was the world language at the end of the 19th century after a century of imperialism, and American English is the world language today after the American 20th century, then the language of the 21st century might well be Inglish or at least an English heavily influenced by India (and China, to a lesser extent).

So what will happen to our mother tongues? This is the insecurity behind the ancient, paralysing debate over teaching English in primary schools. The vernacular chauvinists believe our languages and cultures will die under the mesmerising dominance of the 'power language'. They point to Gaelic and Welsh, which were eradicated by English. Vernacularists think we have made a pact with the devil—fluency in English gives us a competitive advantage, losing our mother tongue impoverishes our personality.

"Can English satisfy the imaginative hunger of the masses?" asks Kannada writer U.R. Ananthamurthy.

"Give me a break," retorts the poet Arvind Mehrotra. "The masses don't have imaginative hungers, and who is satisfying them anyway?"

Ananthamurthy proposed to the Kerala government that 'kacca' or spoken English be taught from the 1st standard, with the medium of instruction being Malayalam. I don't agree. Unless you acquire the nuances of English before 10, you are disadvantaged. But I have confidence in our culture. When Indians embrace English in order to win in the global market place, they don't turn their back on their mother tongue. While English empowers us, our mother tongue continues to give us identity. I agree with Ananthamurthy that in our big cities, we retain our 'home tongues', while using a 'street tongue' and working in the 'power tongue'.

In a wonderful essay, Cosmopolitan and Vernacular in History, Sheldon Pollock, a Sanskrit professor at the University of Chicago, says our vernaculars were also 'created' and are not primordial, as vernacular nationalists would like to believe. The vernacularisation of Sanskrit began in the 9th century as Kannada and Telugu became the languages of literary and political expression in the courts of the Rashtrakutas and Chalukyas. Hindi was fashioned by Sufi poets in principalities like Orcha and Gwalior in the 15th century. Bearers of these languages were the elite and not the people, as Gramsci and Bakhtin made us believe. Our consciousness of a 'mother tongue' didn't even appear until the Europeans arrived. Languages are evolving things, we ought not to do too much social engineering. Vernacular nationalism is bad because it goes against the people's wishes. Instead of encouraging them by creating more English teachers, nationalists thwart their democratic aspirations. Why not celebrate potential gains, instead of worrying about phantom losses. Why not celebrate cool Inglish!

Tags