Many Small Trees Grow

When justice is slow, try conquering hate with love

I, only a young, budding lawyer at the time, was even more vulnerable to the mobs roaming the streets, baying for blood after Indira Gandhi’s assassination. Miraculously, I escaped them on the evening of October 31, but on November 2, my house was attacked. Thanks to my Hindu landlord, who hid us in his storeroom, my pregnant wife and I were saved.

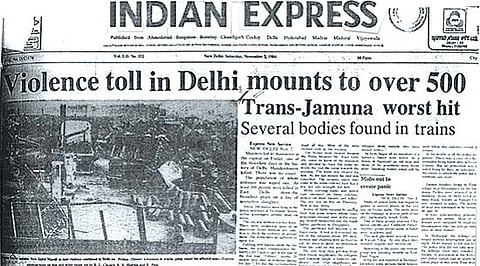

I was lucky, but nearly 4,000 of my fellow Sikhs were not. (Though the official death toll in Delhi is 2,733, in 1985 we submitted a list to the Ranganath Misra Commission, of 3,870 persons killed.) The worst affected was Delhi’s east district where, according to official figures, over 1,200 Sikhs were killed on November 1 and 2. Where was the police, you might ask. Well, the police made 26 arrests here, but, unbelievable though it may sound, those arrested were Sikhs—members of the very community being targeted and slaughtered by the mobs! Logbook entries and evidence from the police control room later showed the police only went to places where they got information of Sikhs defending themselves. For three days, mobs killed, looted and raped openly and not one member of a mob was arrested for the first two days. The arrests began only on November 3, when the government decided to control the violence—and within hours the situation was under control.

A glaring example of the police-mob connivance was at Pusa Road in the Patel Nagar area, where a Mahavir Chakra awardee, Group Captain M.S. Talwar, fired at a mob that had set his house ablaze. The police failed to come to his rescue despite repeated calls, but after he fired at the mob, police and army arrived, led by the commissioner of police, arrested Talwar and jailed him for over two weeks. Not a single member of the mob was held. When I asked the SHO of the area, who appeared before the Nanavati Commission, why no one from the mob was arrested, his answer was, the police was outnumbered. How two truckloads of soldiers and policemen were outnumbered remains a mystery.

That very month, as a junior lawyer, I began pursuing cases relating to the carnage and have been pursuing them since. They are unlike any other cases I have handled, in that, for years they were simply not allowed to proceed. Extraordinary though it sounds, a single FIR was filed for 292 murders committed at different places at different times between November 1-3, 1984. This (FIR 426/1984) was registered on November 3 for the killings in different parts of Trilokpuri, one of the worst affected areas. Over a decade later, in 1995, thanks to an order by Justice S.N. Dhingra, who was then additional sessions judge, the challans were split, and this one FIR was divided into 50 different cases. Only after that did some of these cases lead to convictions. Until 1995—that is, for all of 11 years—there had been only two convictions in the Delhi carnage cases.

In 2002, we saw a repeat of 1984 in Gujarat, but due to the Supreme Court’s promptness in appointing an independent special investigation team, cases could not be covered up so blatantly. In the case of the 1984 carnage, out of 2,733 officially admitted murders, only nine cases led to convictions. Just over 20 accused have been convicted in 25 years—a conviction rate of less than 1 per cent.

One of the basic principles of criminal jurisprudence is that punishment to the guilty should act as a deterrent for the future. Does such an abysmal rate of conviction and punishment serve to act as a deterrent or does it send out the message that one can get away with committing heinous crimes? Think: if the guilty of 1984 had been punished, perhaps the Gujarat carnage would not have happened.

The year 1984 also completed the evolution of a certain brand of politics of violence—belonging to the ruling party led murderous mobs. It saw the beginning of a disturbing trend of political parties complicit in the mass killing of citizens winning elections with a thumping majority—Rajiv Gandhi’s Congress in December 1984, the Shiv Sena in Mumbai in 1993 and Narendra Modi in Gujarat, in 2002.

It was primarily due to the active role played by the media that official connivance in the killings was highlighted in Gujarat 2002. Nothing of this sort happened in 1984. Barring exceptions, the voice of the media was subdued. But recent media responses to the 1984 riots, and equally to the situation in Gujarat after Godhra, have been encouraging. In 2007, my book When a Tree Shook Delhi: The 1984 Carnage and its Aftermath, co-authored with senior journalist Manoj Mitta, received tremendous response—there was hardly a newspaper or magazine that did not review it favourably. The Congress party, however, maintained a studied silence, despite all the damaging disclosures in the book. Given its own dubious record, it is no surprise that the so-called secular party could not muster the will to pass the Communal Violence Bill promised in the Common Minimum Programme of 2004.

Having pushed our justice system to its limits over two-and-a-half decades, my associates and I have decided to observe the 25th anniversary of the massacre with a life-affirming gesture. In July this year, we initiated a massive tree plantation programme across Delhi as a tribute to those killed in 1984. We plan to plant and tend 25,000 trees in Delhi through Gyan Sewa Trust, a registered charity. The 1984 killings were meant to teach a lesson to the Sikh community. The lesson we seek to impart in turn is to respond to hate with love, death with life. We trust the trees we have planted will not only help us remember the victims of 1984 but also prevent the recurrence of such a terrible crime on any community.

'09: Where probe panels failed, a scribe’s shoe succeeded: Tytler, Sajjan denied tickets.

(H.S. Phoolka is a senior Supreme Court advocate.)

Tags