‘Radia Tapes Weren’t Authentic, They Were Manipulated’

A year after the Radia tapes were leaked, Vir Sanghvi, one of those implicated in the conversations, says he has definite proof that the tapes were doctored

These tapes had apparently been made by the income-tax department, which had tapped Radia’s phone. Though there were said to be over 5,000 conversations, only a tiny fraction were actually leaked. But the leakers had organised them well, providing transcripts and arranging the tapes so that Radia’s conversations with relatively well-known people were bunched together and featured prominently.

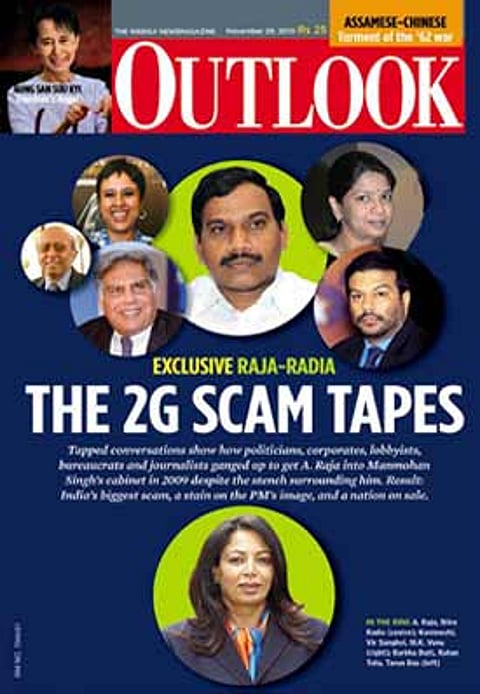

Though there were at least 25 journalists on the tapes—which you would expect given that Radia’s job was to do PR for her clients—the first set of leaks prominently featured three editors, all of whom duly had their faces plastered on the cover of Outlook. One of them was me.

My conversations with Radia were not about telecom, despite packaging that suggested the contrary. They occurred in the period just after the UPA had won its second term and the Congress and the DMK were squabbling. I spoke to several sources, including Radia, during that very newsy time, extracting information about what was happening by probing and stringing them along.

The problem was that while I did indeed speak to Radia, the tape that was published differed significantly from my recollection of the conversation. Obviously, it had been edited, doctored and manipulated.

I immediately wrote out a response on my website stating this. I repeated this in the Hindustan Times and I told everybody who would listen (interviewers, the Public Accounts Committee, the Press Council etc) that the tapes were not authentic.

Having made my position clear, I looked for ways to prove that the tapes had been doctored. This turned out to be more difficult than I had anticipated. Audio labs told me that with modern technology, editing and manipulation done to digital files by a professional can be almost untraceable. Crestfallen, I abandoned this line of investigation.

Then, several months later, a Shanti Bhushan CD was sent anonymously to the media. This purported to contain a 3-way conversation between Shanti Bhushan, Amar Singh and Mulayam Singh in which Bhushan suggested that his son, Prashant, could fix a highly respected judge.

When I heard the tape, I knew that it was a fake. I don’t always agree with the Bhushans but their integrity is beyond reproach. Moreover, the judge in question is scrupulously honest and highly respected. Obviously, this tape had been doctored as well.

The problem was simple: the voice on the tape sounded—to the naked ear, at least—like Shanti Bhushan’s. Moreover, a government lab said the tape was authentic. Bhushan filed a complaint with the Delhi police who sent the CD to another government lab. This lab also said that the CD was authentic. I understood then why the audio technicians I had spoken to had been so discouraging. With modern technology, it is possible to create near-perfect fakes.

Then, Prashant Bhushan surprised me. He managed to find two labs, one in Hyderabad and one in America, that conclusively demonstrated how the CD had been faked and the conversation fabricated.

Encouraged by the Bhushan case, I decided to try again. Because I knew that there would always be a question mark over any tests conducted by Indian audio labs, I looked for top-quality laboratories abroad, seeking out forensic investigators who knew nothing about the case, had never heard of me, and had no axe to grind.

I first went to Forensic Audio, a respected Los Angeles company regularly used by the US Secret Service and the fbi. Kent Gibson, Forensic Audio’s founder, told me what I already knew: it might be impossible to find evidence of editing. I asked him to go ahead anyway. He used five different techniques, including digital spectral analysis, searching for anomalies using sis Editracker software and looking for discontinuities in background noise.

His conclusion both vindicated and relieved me. He found four places where the tape had been edited or manipulated. He declared, “I can say with 90 per cent certainty that the tape cannot be considered authentic.”

Finally, I had the proof I needed. But because I wanted to be doubly sure, I decided to also approach Lawdio Inc, another audio lab used by the US attorney’s office and law enforcement agencies. Once again, Lance McVickar, president of Lawdio, warned me that phone conversations were notoriously difficult to test for conclusive evidence of fakery. But McVickar downloaded the tape from the Outlook website and tested it anyway.

Forensic Audio had found four instances of doctoring. Now, McVickar found five instances of manipulation, with “missing words and broken phrasing”. His conclusion was that “within a reasonable degree of certainty” the tape was not original and had probably been ‘manipulated’.

With two audio labs in the US confirming that the tapes were not authentic, that left one bit of unfinished business: a conversation between Niira Radia and myself in which I seemed to agree to write a column to her specifications.

I remembered talking to Radia for two columns I was writing about the way in which businessmen were cornering India’s scarce resources. I spoke also to Tony Jesudasan, who handles PR for ADAG and one of the two columns specifically mentioned the conversations, naming both Radia and Jesudasan. The problem was that the conversation I actually had with Radia was significantly different from the conversation on the leaked tape.

[See the Niira Radia - Vir Sanghvi tapes: #80, #2.5 and also Niira Radia discussing the Counterpoint article with her colleague Manoj Warrier:#84]

So, I had been Shanti Bhushan-ed. It sounded like me but the tape had probably been electronically synthesised from different conversations. To the naked ear, it sounded like my voice. But a good audio lab could tell the difference.

With three respected labs in America and England saying that the tapes were manipulated or faked, I don’t think anyone can claim any longer that they are authentic. But two questions remain. First, who did it?

Frankly, I don’t know. Neither does the government—or so it says. Its current position before the courts is that these tapes were not leaked from the I-T department and that perhaps service providers had illegally tapped Radia’s phone. Moreover, the government has not been able to convincingly explain why the taps were ordered in the first place. It has changed its story from income-tax investigations to alleged threats to national security.

Off the record, government sources told me last year that corrupt officials had made the tapes at the behest of corporate interests and that genuine and false tapes may have been mingled in the I-T department’s archives. The tapes were leaked as a diversion, they suggested, to throw the media off the scent while those actually involved in the 2G scam used the time to clean up their money trails before the CBI eventually chargesheeted them.

On the other hand, corporate sources told me that this was too major an operation for any business house. They said that the leaks were a symptom of a war within the cabinet, where ministers were even bugging each other’s offices. I laughed dismissively then. I am not laughing now.

The second and more important question: what should the media do when presented with seemingly convincing tapes?

I have no right to get self-righteous about Outlook because, in my career as an editor, I have also carried tapes without verification. Besides, how reliable is verification, anyway? Consider the Shanti Bhushan tape. Though it is an obvious forgery, the government still maintains that it is genuine and has lab reports to back its case.

So, here’s what I think. Technology has now advanced to the stage where fake documents, morphed photos and fabricated tapes are all too easy to create. As journalists, we simply lack the expertise to tell what is genuine and what is a fake. So, perhaps the time has come for us to be more cautious. Just because something sounds right, it does not follow that it is genuine.

Technology can make fools—and liars—of us all.

Also See:

- See the Niira Radia - Vir Sanghvi tapes: #80, #2.5 and also Niira Radia discussing the Counterpoint article with her colleague Manoj Warrier:#84]

- Vir Sanghvi's response on his blog - and also the following Web Editor's note we carried in 2010:

Tags