Infant Mortality Rate (IMR), the probability of an infant dying before reaching the age of one, is often used as an indicator of a country’s health and development. It sheds light on the availability and quality of health services, poverty, and socioeconomic status, and well-being of children and families across the globe. High infant mortality rates are generally indicative of unmet human health needs in sanitation, medical care, nutrition, and education.

What India’s Infant Mortality Rate Tells Us About Its National Health

India ranked 47 in the list of 225 countries with the greatest number of infant mortality cases, according to the Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) 2017 estimates.

Even though preserving the lives of new-borns has been a long-standing issue in public health, social policy, and humanitarian endeavours, infant mortality is once again on a global rise even after a slow decline. An exploration and determination of key data and metrics can shed more light on this trend and its drivers.

GLOBAL IMR VS. INDIA – A COMPARISON

Live birth definitions often vary widely between countries. Reporting can be inconsistent or understated, depending on a nation’s live birth criterion, vital registration system, and reporting practices (Fig 1).

Fig. 1 – Differing IMR criteria by country

The UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (IGME) applies a common estimation method across all countries in the interest of comparability to tackle this problem. This method was designed to estimate a smooth trend curve of age-specific mortality rates, accounting for potential outliers and biases in data sources and averaging over the possibly many disparate data sources for a country, which can include household surveys, censuses, and vital registration data. Figure 2 represents the UN IGME’s broad strategy to arrive at annual estimates.

Fig 2 – Process of arriving at annual estimates of mortality rate by IGME, Source: UN IGME

Definitions – FBH: full birth history; SBH: summary birth history; HH: household deaths, SSH: sibling survival history

Fig 3 – Infant Mortality Rate as per IGME estimates

Globally, the average infant mortality rate in 2019 was 28 (per 1000 live births) according to the United Nations. The projected estimate for 2020 was 30.8 per 1000 live births according to the CIA World Factbook, Afghanistan is estimated to have the highest IMR of 104.3 while Slovenia is estimated to have the lowest IMR of 1.7 infant deaths per 1000 live births according to CIA.

A DEEP DIVE ON INDIAN DEMOGRAPHY

Across India, there were 721,000 infant deaths in 2018, per the United Nations’ child mortality estimates. That is 1,975 infant deaths every day, on average, in 2018.

From a global perspective, India ranked 47 in the list of 225 countries with the greatest number of infant mortality cases, according to the Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) 2017 estimates. Iraq, Kenya, Zimbabwe, Bangladesh, etc., had better survival conditions for infants.

Fig 4 – Infant Mortality Rate, India, 2017. Source: SRS Bulletin

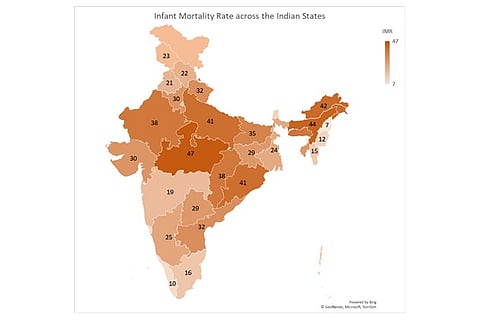

UNDERSTANDING THE DIFFERENCE IN IMR BETWEEN INDIAN STATES

We believe a universe of underlying factors drive this variance and finetuned a selection for closer study. We understood their individual relationship with IMR by calculating their correlations.

Fig 5 – Correlations of possible drivers and infant mortality rate (Source: internal analysis)

After studying individual correlations, the most significant were-

- Literacy Rate (%)

- Female Literacy Rate (%)

- Birth rate

- % stunted (under 5 years)

- Percentage of children whose stools are disposed of safely

- Urban population

- Rural Population

- % of doctors and nurses

- % underweight (under 5 years)

- GDP Per capita ($)

- # Hospitals beds per 1000 people

Fig 6 – Scatterplot of 3 most significantly correlated drivers (Source: internal analysis)

We ultimately drew from a combination of three variables – Literacy Rate and Birth Rate after running a multivariate regression using step wise selection tool of IMR with all these highly correlated variables.

Improving literacy rate and decreasing birth rate by 10% can result in a better dynamic for the Indian IMR rate with a potential 45% improvement according to our model (Fig. 7).

Fig 7 – Predicted IMR for India in response to key population health intervention andeducation(Source: internal analysis)

CAUSE AND EFFECT OF TOP TWO VARIABLES?

We can see infant deaths are symptomatic of deeper social problems such as educational disparity, rather than just medical aspects.

- Literacy can play a significant role in reducing infant mortality rate. States with more educated women show better health outcomes for children. States with the highest IMR–Madhya Pradesh, Assam, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan–also have fewer women with more than 10 years of education.

- The relationship between birth rate and higher mortality rate is bi-directional. Reductions in fertility contribute to falls in infant mortality by enabling parents to devote more time and resources to their children. The higher mortality in case of high birth rate could also be related to the effect on infants and children of earlier weaning and reduced care from mothers. The causation could reverse course in the form of Replacement and Lay Up. Replacement will refer to the couples extensively replacing an actual infant or child death with a new birth. Lay Up refers to the families, even those who have not experienced a child death, having children more than a desired number as a precaution in the event of child loss.

A POTENTIAL WAY FORWARD

India has recorded a significant fall in the infant mortality rate in the last five years and may improve the situation further by tackling these longstanding social issues. Further reduction in India’s child mortality rate calls for new approaches to the problem of child mortality.

One solution could be taking a holistic approach to address the combined need for education (such as universal primary education and access to basic maternal and infant health services).

Apart from implementing concrete policies to provide education to all, there is also a need to introduce important topics in the curriculum such as contraceptives, sex education, and family planning. While it is established that a literate person is better positioned to make educated decisions on behalf of their infant, the introduction of such new topics could make important concepts related to fertility and maintaining a stable birth rate more accessible.

This research is just the beginning of an exploration of a deeply entrenched and multifaceted problem. Understanding IMR risk factors and how they vary by region and state is a crucial first step for policymakers or other non-government decision-makers. Stratified health policies that consider the measurable key facets discussed in this article and state-specific epidemiological and demographic patterns could be a doorway to a healthier India and a healthier world.

(Anoushka Khanna is an analyst at FischerJordan and Neet Shah is a partner at FischerJordan, a consulting firm that combines Strategy, Analytics and Technology practices within a single cross-disciplinary unit )