As India turns 60, so do they. Born in 1947, these Midnight's Children—artistes, thinkers, politicians, sportsmen, actors—have made their mark, in their individual ways, on the life of the nation. Outlook invites them to look back on their lives, and the nation's. What does being Indian mean to them? Do they feel a shared sense of destiny with the nation? What makes them proud of India, what makes them despair?

Children Of 1947

Those born in the Year look back on 60 years of their, and the nation's, lives

***

Politician

"You can’t choose your caste or class, but you can choose the class of people you work with—politics in India gives you that choice," says the firebrand Karat. She made her choice in 1970, chucking a ground job with Air India in London to join the Communist Party of India (Marxist), with a textile trade union as her entry point. Reflecting on her life, and the nation’s, she says: "For all of us in the Communist movement, it is not India as it is, but a different kind of India that we are fighting for. We are under no illusion that the present structures cannot deliver—that Independence just marked a beginning." What excites her most—and depresses her—about 60 years of independent India relates to the area she has been most actively involved in—the women’s movement. "Many young women have crossed aspirational expectations of so many kinds, but there are many others unable to cross the hurdles—it is frustrating to see such a huge resource, such huge talent being wasted."

Carnatic violin maestro

He was born a month before Independence, and his father was overjoyed. "The original name he gave me was Lakshminarayana Sudhindra Balasubramaniam—Sudhindra means freedom in Tamil—but it was too long," says the maestro. His early years were shaped by the experience of living in Jaffna, amid a rising cycle of Tamil-Sinhala violence. His family escaped and returned to Chennai, his birthplace. "We had to work hard, build our lives from scratch. But to be able to walk in the street with no fear, that’s when I learned what freedom was," he says.

In the decades since, he has seen India—and with it, Indian music—move from strength to strength. "No one talks about India as a third world country. We have progressed in every field, including music. It’s not the appreciation of the ’60s, when it was all easy spirituality and drugs. At international festivals I see other artistes performing Carnatic; people are serious about learning it."

Wellness guru

"I guess my destiny was woven into India’s," says Deepak Chopra. "We were both born at the same time and somewhere subconsciously, there was the impulse to influence the world with India’s cultural and spiritual heritage."

Sharing what he learnt from India with the world has been a great high. Yet, the New York-based wellness guru points out, India can be a roller-coaster ride of emotions. What bothers him most is the "extreme nationalism" he sees among Indians, which is "divisive and destructive". "In the new global environment, nationalism (which has been a trait that I have had in the past) will have less and less relevance," he argues. "Economic growth is progress but we also must be aware of our prejudices, ethnocentrism, bigotry, corruption, power-mongering and influence-peddling."

While he speaks soberly about India’s malnourished children, "abject poverty" and the AIDS epidemic, Chopra is upbeat about the future. "Our time has come," he declares. "India has never colonised the world through militarism. Despite a lot of problems, we are now the emerging economic and cultural global force. The Indian diaspora has spread to every nook and cranny of the world. Colonisation in reverse and of a better kind is happening and we are all part of that tide."

Actor

She was born not just that Year, but on the Day. When she realised its importance, at age 7 or 8, it left her "with a peculiar feeling.... It makes you feel very warm, thinking about what people went through for independence." But memories for the light-eyed Bengali beauty are bitter-sweet. "My parents were driven out of East Bengal. By the time the nation became independent, we’d lost everything, my father was penniless. He still can’t forget it," she says.

Looking back on 60 years of nationhood, Rakhee recounts the high points. Among them, "our scientific and cultural development. Politicians have not done anything good for citizens. Our judiciary is the only strong force: it’s the Supreme Court that’s running the country." She blames citizens too: "Our nation is running on hype and trivialisation. The growing politics of hate is disconcerting, how did this hatred creep in?"

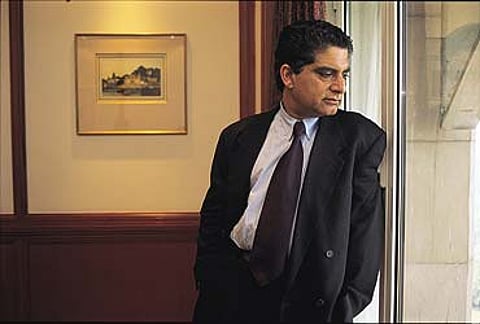

Politician

"I’m very conscious that I am a product of Independence and democracy," says Digvijay Singh. "I was born in a zamindar’s family, but my father was not a conventional landlord. He threw open the family temple to Dalits in 1947, responding to a call given by Gandhi. Later, he donated 5,000 acres of land as part of the Bhoodan movement." But, even though the trajectory of Digvijay’s life followed that of the nation, he confesses he "never consciously felt the connection" till he was 22, when his father unexpectedly died, and he was "sucked into the whirlpool of Congress politics". It was then that the realities of independent India hit him. He joined politics in his hometown of Raghogarh, and was expected to take off from where his father had left off. He did, serving as chief minister of Madhya Pradesh from 1993-2003. He believes that "India’s social, educational and economic achievements in the last six decades are unprecedented". But it is in village India that Digvijay sees "enormous changes—an improvement in the quality of life even among the poorest and least privileged".

Former cricketer

Chetan Chauhan, born just three weeks before Independence, believes that he did well by India in his glory days, when he opened for the country along with Sunil Gavaskar—and that India has done well by him. "Together, Gavaskar and I changed the perception that India did not have a pair of openers who were strong and complemented one another. Of course, I was overshadowed by Gavaskar’s strong presence. I guess my contribution to Indian cricket was recognised after I had called it a day," says Chauhan philosophically.

Chauhan lived in Australia for some years but came back because he believed his destiny was linked to India. He gets disturbed when he sees poor and lower middle class people struggling, but says the former MP, "I am proud of India’s rich heritage and its society. We have a great deal of common sense that I don’t find in many nations. We read and are curious to know more. We are patient and tolerant—perhaps we tolerate some nonsense as well." Such as? "We can do without politics in our offices, cricket and society."

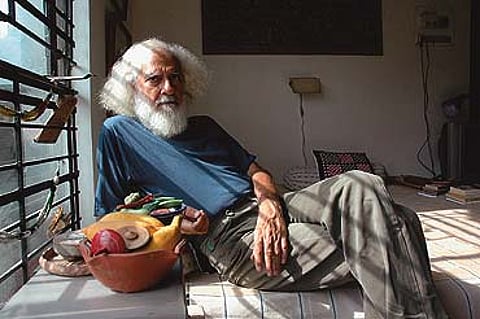

Poet

Being born in 1947 never meant much to the poet. "I don’t feel anything particular," he says. "I don’t care about the new-fangled, large formulations of nation. I am suspicious of these grand gestures. How does it impact individual lives? We just lead our lives." The one time he did become aware of "nation" was when Indira Gandhi declared the Emergency. "You couldn’t ignore the ‘nation’ then. It was a scary moment, utterly terrifying. It was then that the notion of nation became a dangerous thing." says Mehrotra. "The only other comparable event has been the rise of the BJPWhat makes Independent India special for the author of Disappearing Daughters, a hard-hitting book on one of its bleakest practices, female foeticide? "Freedom of expression and respect for achievement: even if you’re an item girl," says Aruvamudam promptly. Looking back on freedoms fought for, and won, she says that each generation has its own battles to fight, and takes the freedoms won by the previous generations for granted. "My generation wanted to fight for independence from the social mores suffocating us. The present generation is fighting for independence of individual thought and earning capacity." and the fall of Babri Masjid."

Feminist and journalist

What makes Independent India special for the author of Disappearing Daughters, a hard-hitting book on one of its bleakest practices, female foeticide? "Freedom of expression and respect for achievement: even if you’re an item girl," says Aruvamudam promptly. Looking back on freedoms fought for, and won, she says that each generation has its own battles to fight, and takes the freedoms won by the previous generations for granted. "My generation wanted to fight for independence from the social mores suffocating us. The present generation is fighting for independence of individual thought and earning capacity."

Theatre director

"My grandmother was a staunch Gandhian," says Allana, fixing on the true point of origin of her life’s story. "The household she ran was the centre of the theatre community in Bombay. It was full of young people in their 20s, excited about theatre, about the British leaving...I was born in the middle of that." Her father, Ebrahim Alkazi, was the first director of the National School of Drama, directing his first play in its aangan. "Nationally, there was the same feeling: that we were building institutions from the ground. Gandhian simplicity, Nehru’s idealism, they were still infecting people around me."

As the decades rolled, institutions stopped resembling the dreams that created them. However, says Allana, Indian theatre continued to grow, adapt, change. The ’70s, she recalls, were all about returning to your roots, "rediscovering Yakshagana, redoing Kathakali, rejecting Western things.... Today, I suppose, we aren’t rejecting anything at all," says Allana, gesturing around, as though at the cultural anarchy of South Delhi. "But in this phase of globalisation, we’re lucky to be carrying some kind of tradition and to also be exposed to the world. I’m free to take and snatch, to beg, borrow or steal from anywhere."

Actor

He enjoys the idea of being born in the same year as his country. "It feels very good to have been part of a free India where you can say what you want, express yourself, do everything you would want to do," says Kapoor. He is also proud to be part of a family "of four generations of entertainers.... We have dedicated ourselves to bringing joy to the lives of people". The lowest point in the nation’s history for him was the Emergency. "It saddened me," he says, simply. But now this "very optimistic Indian" feels a great sense of well-being. "We have come a long way," he says. "It’s a very good phase to be in. My driver’s kids work in a BPO, such an opportunity never existed earlier. The next decade will be even better."

Interviews by Ashish Kumar Sen, Smita Gupta, Namrata Joshi, Raghu Karnad and Shruti Ravindran

Tags