Lutyens' Delhi

He's a one-man brand for New Delhi's heritage but does he deserve all the credit? Setting the record straight

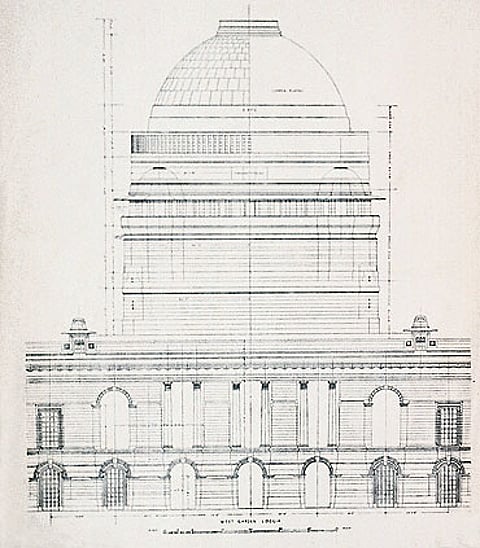

- Rashtrapati Bhavan

- Four bungalows inside the President’s Estate

- India Gate

- Hyderabad and Baroda palaces at India Gate

***

Robert Tor Russell built Connaught Place, the Eastern and Western Courts, Teen Murti House, Safdarjung Airport, National Stadium and over 4,000 government houses.

E. Montague Thomas designed and built the first secretariat building of New Delhi which set a style for the bungalows.

Herbert Baker made seven bungalows and the North and South Blocks.

The other bungalows of New Delhi are the work of architects like W.H. Nicholls, C.G. and F.B. Blomfield, Walter Sykes George, Arthur Gordon Shoosmith and Henry Medd.

Lord Hardinge insisted on roundabouts (Lutyens had initially designed the streets at right angles), hedges and trees (Lutyens said the trees wouldn’t survive) and demanded the Raisina Hill site for the Viceroy’s House (Lutyens preferred a more southern setting closer to Malcha). Hardinge also insisted on a Mughal-style garden for Viceroy’s House (Lutyens was keen on an English garden with ‘artless’ natural planting).

Using P.H. Clutterbuck’s list of Indian trees, W.R. Mustoe, director of horticulture, was actually responsible for the roadside planting work for New Delhi’s avenues. It was Mustoe and Walter Sykes George who landscaped and planted Lutyens’ Mughal Garden.

Swinton Jacob, advisor on Indian materials and ornaments, suggested raising the ground level of Rashtrapati Bhavan, on a carefully studied contour plan.

***

Today, Delhi’s building activity has spilled beyond its boundaries to fashionable second homes called ‘farmhouses’. Indian architects and interior designers create sprawling dream homes amidst acres of landscaped abundance, imitating the loggia-encircled dwellings set in English gardens which the early-twentieth century had realised in New Delhi. To the layperson, any colonial bungalow in Delhi is a Lutyens house—the misperception is as inaccurate as the mispronunciation, ‘Lootens’ instead of ‘Lutchens’. But then Delhi’s nouveau riche choose to appropriate the ‘Lutyens style’ for their own snobbish purposes, with as fine a disregard for pronunciation as for architectural verity.

History and the connotations of Empire apart, a bungalow home—should one have the space—is ideally suited to the tropical climate of Delhi. Large, open verandahs, apart from their elegance, keep the inner room cooled away from the direct rays of the sun, while high ceilings carry the hot air up, to be let out from the ventilators. Even with air conditioning a bungalow adapts itself well and gives more than enough headroom to de-stress from urban claustrophobia and clockworks.

As there is a renewed interest in building colonial bungalows to suit Delhi’s farmhouses, it’s time to ask, "Who designed New Delhi’s stunning white bungalows?" And why does the credit always go to someone else? Both clients and architects need to educate themselves and get their facts right.

***

It should be remembered that even before Herbert Baker and Edwin Lutyens set foot in India, E. Montague Thomas had designed and built the first secretariat building of New Delhi which set a style for the bungalows. Later, when the North and South Blocks (then called the secretariats) were designed by Baker, and Rashtrapati Bhavan designed by Lutyens, the bungalows of the new imperial capital were evolved from the existing style by a host of architects. What conservationists today call the LBZ (Lutyens’ Bungalow Zone) has not a single bungalow designed by Lutyens except within the President’s Estate. So what are the other contributions he is credited with and what actually is the true credit he deserves?

***

***

***

***

***

***

***

***

Lutyens’ talent is hugely overrated for his times. He was flaunting classical styles to evoke the decadent and last phase of empire. Lutyens had been unperceptive enough to pass a sweeping judgement on all of India’s standing architectural heritage when he wrote: "They are just spurts by various mushroom dynasties with as much intellect in them as any other art nouveau." If Lutyens’ own work is put to scrutiny under his patronising view, it was also just a spurt. He may have immodestly imagined that the Delhi Order which he created for the capitals of his pillars would match and last with the five classical orders—the Doric, Corinthian, Ionic, Tuscan and Composite. His clapper-less bells were to hang out of the capitals to hauntingly sound the death-knell of the British empire. Design apart, where had Lutyens made provision for the new inventions of the age which had come with industrialisation? Corbusier was only 18 years younger than Lutyens. His Chandigarh was built 30 years after Viceroy’s House, but his modernism, perhaps equally irrelevant and inappropriate for India, makes the town look a century ahead of New Delhi. Today, almost all the English commentators on Lutyens have to explain with embarrassment the architect’s remarks on India. According to Gavin Stamp, Lutyens is "guilty by association", Elizabeth Wilhide writes that "Lutyens’ impressions of India do not always make sympathetic reading", and Roderick Gradidge suggests that they were "vulgar...[and he] may have brought these expressions with him from England." William Dalrymple has recorded his impression of Lutyens upon reading the architect’s correspondence: "Perhaps the overwhelming surprise of the letters is Lutyens’ extraordinary intolerance and dislike of all things Indian. Even by the standards of the time, the letters reveal him to be a bigot, though the impression is one of bumbling insularity rather than jack-booted malevolence. Indians are invariably referred to as ‘black’, ‘blackamoors’, ‘natives’, or even ‘niggers’. They are ‘dark and ill-smelling’, their food is ‘very strange and frightening’ and they ‘do not improve with acquaintance’. The helpers in his architect’s office he describes as ‘odd people with odd names who do those things that bore the white man’. On another occasion he writes of the ‘sly slime of the Eastern mind’ and ‘the very low intelligence of the natives’." Lutyens came to the conclusion that it was not possible for Indians and whites to mix freely as "They are very, very different and I cannot admit them on the same plane as myself."

***

Herbert Baker had been a forerunner to Lutyens in designing Pretoria’s Union Buildings. The resemblance to New Delhi’s Great Place (Vijay Chowk) is staggering. But poor Baker was consciously sidelined and trampled by Lutyens who had so cunningly used him to win the New Delhi commission jointly. History forgets this, as also the fact that Lutyens’ war memorials in Europe are a copy of those that Baker designed. That Baker finally returned to England heartbroken and died after a nervous breakdown is something Lutyens’ conscience would never quite be able to wash off.

It is a great pity that the statue of Lord Hardinge, New Delhi’s founder, was removed from beneath the Jaipur Column—for this city would not have seen the light of day without him—and that Lutyens’ still remains within Rashtrapati Bhavan.

***

For all their rivalry and the vicissitudes of fame there’s no question that Messrs Lutyens and Baker worked long and hard on the monumental project that was New Delhi. Surely they deserve memorialisation somewhere on the sprawling landscape of the capital? A couple of streets named after them perhaps?

Well, as it turns out, that honour was bestowed long ago. On an early map ‘Lay Out Plan of New Delhi’ from the papers of the legendary contractor Teja Singh Malik, both architects appear in uncomfortable proximity to each other.

Tags