The Indian Design community went into a collective depression on hearing the news that Professor MP Ranjan is no more. Hailed as the Design Guru, Ranjan, 64, was a senior professor and a principal faculty at NID, Ahmedabad.

The design fraternity is still in denial and is mourning the loss of its biggest champion. The outpour on social media that started as a huddle on Facebook, has now grown into a huge avalanche of web pages, groups, multimedia tributes, blogposts and Wikipedia entries.

After his death on 9th August 2015, memorial services and remembrance meetings have taken place in several cities, including Ahmedabad, Delhi, Bangalore, Pune, Mumbai, Chennai, London and San Fransisco, reinforcing the effect he had on people. There was also one in the village Katlamora in Tripura, where he worked on building a design institute for the craftsmen.

"Ranjan was many things to many people," writes Sajith Ansar. "He was an educator and a mentor, pushing boundaries and encouraging each of us to do more and think more. He was a design evangelist, speaking up for causes and being a catalyst of change. He was a source of inspiration, igniting in each of us an ability to think beyond our abilities. He was a farmer, planting within each of us the seed of curiosity and discovery."

Ranjan was all this and more. He was busy juggling all these roles and he did these effortlessly. Ranjan had a lasting influence on the lives he touched and the students he taught. He taught his students that design-thinking is a powerful tool that can be used to usher in change. He made every student feel special and important and was always connected to them, sometimes, even years after they graduated. He made his students think, perceive, question, grapple and deliver. He was genuinely proud of his students' work and constantly blogged about them. He made it a point to let everyone know about it.

He worked to spearhead the cause of design with missionary zeal. He lamented the lack of understanding of design in successive governments. He questioned the absence of designers in the Padma awards. He was disappointed that several design projects are 'flying under the radar', with no recognition or support. He rebelled against decisions that did not acknowledge this. He was a lone crusader who used blogging to highlight the state of design in India. His blog soon became the authoritative tool for evangelism that merited global attention. He would gleefully rattle off statistics about the fact it had a few million hits and designers from world over were quick to sign up for his posts.

His global moment in the sun came when he was chosen as one of the world's top 20 Design Thinkers of the world along with IDEO head David Kelly and Brad Pitt in the list. He had a sizable number of friends and followers in the international design community as well. Don Norman, author of the book, Design of Everyday Things, writes that, "Ranjan was a warm and compassionate person and a great educator. Thousands of students will mourn. I was pleased to be able to call him my friend."

Harold Nelson, the author of The Design Way had made a lasting impact on Ranjan, who later became his friend and fellow traveller. Nelson writes, "Ranjan and I were just exchanging emails on a quest for new insights into old design terms in design. I will miss him as a colleague and friend of immense integrity and intellectual honesty."

He was born to an entrepreneur father, M V Gopalan in Madras, who influenced him with his design enterprise. Ranjan claimed that while children his age were busy playing with toys, he was busy making them. Sujata Shankar Kumar, a furniture design graduate says, "He would always tell me that the day he was born in the year 1950, his house in Madras got connected with electricity, like he was the brightest star. He said it with that adorable brag quotient he had that few could get away with."

Ranjan's toy-making skills came in handy, when he joined NID to study Furniture Design. As a student of design, he worked on projects alongside design big-wigs like Charles Eames, Frei Otto and Buckminster Fuller, which left a deep influence on his thinking. He returned to NID to become a faculty. As a teacher, he evolved from teaching basic geometrical construction to young foundation students to teaching design thinking and strategising to students across all disciplines through a course he conceived called 'Design Concepts and Concerns'.

His enthusiasm to learn and teach was infectious. He was always enthusiastic to share what he learnt. He would do this either through elaborate posts in his blog or through engaging conversations over chai. Everyone agrees that he was generous and giving, when it came to sharing what he had.

His interests were varied and eclectic. Whether it was geometry or basket weaving, philosophy of justice or information technology, he would do a full immersion into the subject. That's how he was: thorough and intense. He documented the entire cane and bamboo crafts of North East India, along with his colleagues Ghanshyam Pandya and Nilam Iyer. Together, they published the book Bamboo and Cane Crafts, that, to this day is the authoritative guide on the craft. It is both tragic and eerie that all the three authors died well before their time.

His passion to document, his ability to share and his method to simplify complex concepts, all came in handy, when he co-authored a book with his wife and fellow designer, Aditi Ranjan, Handmade in India. The book was published by the Department of Handicrafts, Ministry of Textiles, Government of India and is now the official directory of all the crafts.

MP Ranjan, Design Guru

Ranjan, 64, was a senior professor and a principal faculty at the National Institute of Design, (NID), Ahmedabad.

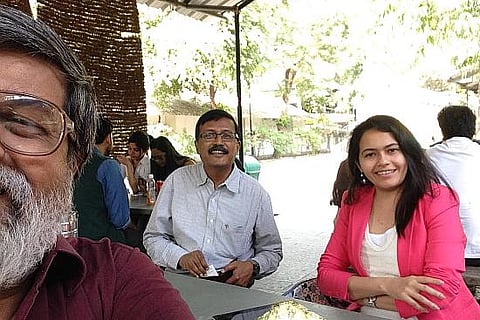

A selfie. Ranjan with A. Balasubramaniam and Mitali Bajaj

While Ranjan enjoyed writing books and blogs and editing compendiums, his iPad selfies with people he met up with, became his hobby. Every time he met someone interesting, he would shoot a selfie and promptly mail these to them. This was his quick process of documentation. It is no surprise that these selfies have turned up all over social media and have also been compiled into a video.

Knowing Ranjan would mean either you love him or you don't. He had a fair share of bosses and detractors, who would not agree with his ideas and his ways. He would appear quite nonchalant about this and go to town about why he is hated by them. He spoke his mind at all forums, which brought a fair share of detractors.

But, he never lost his humour, even in difficult situations and his disarming smile was always an ice-breaker. We were once together in Yojana Bhavan, along with several other designers as a part of his activist team 'Vision First', waiting to meet Sam Pitroda to discuss the lack of vision in setting up new design institutions. Sam walked in, apologising for the AC not being effective in the room. Ranjan, immediately quipped, "We are thankful for the warm welcome!" It immediately broke the ice and set the tone for the discussions.

His ability to connect with total strangers was uncanny. Says Aparna Piramal Raje, industrialist and columnist, "I have interviewed hundreds of people over the years, but Ranjan was one of the few to invest in my learning, not just share his views."

Ranjan was known to be a master of metaphors and models. He had always maintained that all we really have in life is this square foot of earth on which we stand. We face this daunting challenge to work on our own square foot of earth so that it is better and more fertile when we leave than when we got here.

As Ken Friedman, Professor at the Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne and fellow designer, writes, "Ranjan left his square foot better than he found it."

A Balasubramaniam is a practising product designer who runs ' January Design', a design studio in Gurgaon, India. He has both studied and worked along side MP Ranjan at NID. He can be reached at bala[at]januarydesign[dot]com

Tags