The Heroes

An eminent jury picks out Sixty Great Indians in 60 years of our Republic

So while B.G. Verghese allowed that Sunil Gavaskar, Bhupen Khakar and MGR were worthy names, he would rather have had Tenzing Norgay, Sukumar Sen (who organised India’s first elections) and Justice H.R. Khanna (the lone dissenter in the habeas corpus case of ’77 which gave the government unlimited powers under Emergency) instead. Mushirul Hasan wasn’t enthused by A.B. Vajpayee, Sardar Patel and Amitabh Bachchan. Mukul Kesavan thought that a list without Mahashweta Devi, Waheeda Rehman (there isn’t a single Hindi film actress in this list), Prakash Padukone and S.D. Burman had lost its way. But there was only room for sixty and we took comfort in the fact that with the exception of half-a-dozen irreplaceables, you could probably substitute every name in the list with distinguished alternatives. And you probably will!

It’s unfashionable to give individuals credit for a nation’s achievements, specially a nation as large and varied as India, but if there’s a single reason for independent India growing into a civilised republic, it is Nehru’s commitment to a democratic and pluralist state. In his 17 years as prime minister, he made certain that India didn’t slip into the authoritarian and majoritarian habits that turned so many post-colonial republics into failed states.

Sardar Patel

The undisputed boss of the Congress’ party organisation at the time of independence, Patel is often invoked by Nehru-baiters as the greatest prime minister India never had. A dour man, conspicuously indifferent to the anxieties of Indian Muslims after Partition, he is part of the republic’s roll-call of heroes because of the ruthless dispatch with which he coerced and cajoled India’s princes into merging their states with the new republic at a time when everything could have unravelled.

B.R. Ambedkar

Author of the Constitution

Ambedkar is more important in India today than either Nehru or Gandhi. India’s largest state, Uttar Pradesh, is ruled by a Dalit-led party, the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), whose influence and organisation is increasingly pan-India in scope. But even if the politics of Dalit assertion had never come to pass, Ambedkar would be on this list for his role in the framing of India’s marvellously balanced Constitution and as the prime mover behind the landmark Hindu Code bill.

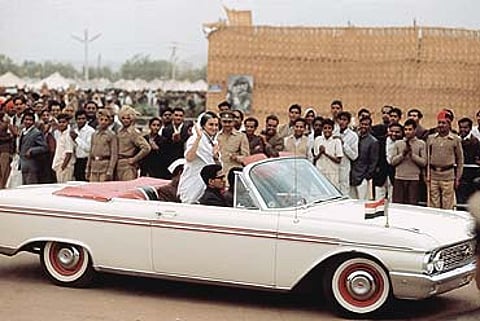

Nehru’s daughter served as PM for as many years as her father, but her political legacy was decidedly darker. She was responsible for the one period of authoritarian rule in India’s history, the Emergency, the politicisation of the bureaucracy and a statist populism that created the high noon of the License Raj. Her abiding claim on history is her inspired political and military leadership in ’71 as she midwifed the birth of Bangladesh and oversaw the breakup of Pakistan.

Half a century ago, he became chief minister of the first popularly elected Communist government in the world. His initiatives in land reforms, literacy and public health did much to make Kerala India’s star performer in the UNDP’s Human Development Index. He was a Left icon who practised what he preached—born a Brahmin, he renounced his caste, and gave away his inherited wealth to the Communist Party.

To Mayawati and her mentor Kanshi Ram goes the credit of finding a strategy that allowed Dalits to parlay their numbers and their entrenched position within the lower echelons of the state structure into real political power. Today, BSP supremo Mayawati wields power not as a subordinate member of a coalition led by privileged groups, but as the head of an electorally potent coalition of diverse social groups with Dalits in the vanguard.

As Sher-e-Kashmir, Sheikh Abdullah brought Kashmir into India but spent his whole life negotiating the terms of that accession. He spent the equivalent of a lifeterm in jails on charges of separatism, but had an utter lack of bitterness towards Nehru-Indira. He died as the CM of the land he had fought so hard for.

For 20 years, he led a bloody insurgency for Mizoram’s sovereignty with help from China and Pakistan, then had the sagacity to realise the futility of violence. He contested elections, became Mizoram’s chief minister—and showed other insurgents the path back to peace with honour.

For 25 years, Maruthur Gopala Ramachandran was the biggest star in Tamil cinema. He turned his fan base into political power, founding the AIDMK, serving as CM for ten continuous years. His greatest legacy was the mid-day meal scheme which at one stroke got kids into schools, improved literacy and addressed malnutrition.

Jyoti Basu headed West Bengal from 1977 to 2000, the longest serving CM in history who almost became PM. His tenure symbolised the mixed blessings of CPI(M)’s rule: land reform and a robustly secular politics on the one hand; industrial flight, economic stagnation and the systematic politicisation of the state’s bureaucracy on the other.

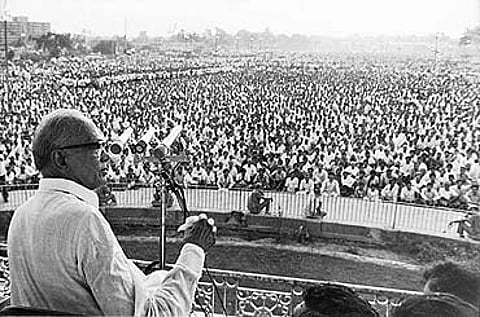

JP spent the first 25 years of independence as the patron saint of lost causes: the Praja Socialist Party, the Sarvodaya movement, even self-determination for Kashmir. His most enduring contribution to the life of the Republic was the movement he led to unseat Mrs Gandhi, which provoked the Emergency. As the eminence grise of the Janata Party, the first non-Congress party to run the central government, he can take credit for catalysing the political forces that set in train the Congress’s political decline.

A member of Parliament for nearly 50 years, Vajpayee’s claim to this list is that he is the only non-Congress prime minister to have served a full term in office. Vajpayee portrayed the possibility that the nakedly anti-minority Bharatiya Janata Party could morph into a right-wing, mildly majoritarian party on the lines of the Christian Democratic parties of Western Europe. This promise was belied by his equivocation in the face of the pogrom of Muslims in Gujarat under chief minister Narendra Modi.

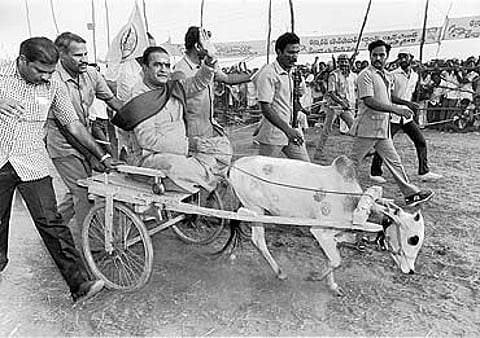

On screen he seduced the Telugu world as Rama and Krishna and was soon regarded as a deity himself. Then he harnessed his star power to whip up Telugu pride and create a powerful political machine that would make regional aspirations and interests a decisive force in national politics.

He is more than just the architect of India’s economic reforms. In an era of corruption, his personal life is above reproach. In a time of intellectual bankruptcy, he tries hard to make ideas fashionable. In a period of bitterly polarised positions, he stands for consensus.

If Periyar launched the Dravidian movement, Annadurai gave it political form by founding the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam in 1949. He fought for upliftment of non-Brahmins, led the anti-Hindi agitation; he also gave Madras its name—Tamil Nadu. His legacy still inspires politics in the state.

Abul Kalam Muhiyuddin Ahmed, known to history as Maulana Azad, was an unswerving opponent of the idea of Pakistan. He was publicly scorned by Jinnah before independence as a Congress showboy. But he took on Vallabhbhai Patel over the security of Muslims in a divided India. At an age when most people retire, Maulana Azad shouldered the enormous onus of becoming not just India’s first education minister, but the most visible symbol of the pluralist claims of the new republic.

Erudite and prescient, he shredded the philosophy of socialism during its noontide, anticipating the cesspool of corruption which Nehru’s economic policies would lead to. India’s first (and only) governor-general, he later founded the Swatantra Party which became the pole around which those opposed to the Congress coalesced, awakening us to the importance of a strong opposition in a democracy.

He planted the seeds of India’s advanced research capabilities, especially in harnessing atomic power—to ignite both bulbs and the bomb. A genius in every area of fundamental physics, he was also a visionary builder of institutions and cultivator of future talent.

What Bhabha was to the atomic project, Sarabhai was to the space project. He established the Indian Space Research Organisation and dictated its lasting creed—that our goal in space would be development on the ground, and the dreams of every Indian would be tethered to every rocket sent into the skies.

India was barrelling towards a Malthusian crisis when he hybridised local wheat and rice with imported high-yield varieties. With his passionate commitment to the adoption of modern agricultural techniques, he has done more than anyone else to banish the spectre of famine and hunger from our land.

India’s "Bird Man", he became an ornithologist before Indians learnt to spell the word. His books are seminal, definitive works on birds of our subcontinent. But his work goes deeper—he helped create environmental consciousness of a new nation, barely aware of the natural wealth that was theirs.

Guiding spirit behind the Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA), she opened everyone’s eyes to what collective action by the country’s poorest women could achieve. And inspired millions of other Indian women to reach for self-reliance with confidence, courage, negotiating power—and yes, access to credit.

An unstoppable force wrapped in a handloom sari, Patkar has emerged as an implacable challenge to the Indian state, forcing it to become accountable for the development paradigm it follows. With every agitation, every hunger strike, she has grown in stature and emerged as the conscience-troubling voice of an India that isn’t so shining.

A path-breaker and institution builder, her contribution to preserving, reviving and promoting Indian art and culture—handlooms and handicrafts to theatre and dance—is unequalled. As impressive was her work as trade unionist, social reformer and activist. She crusaded for women’s rights (she was a child widow herself) and achieved miracles in rehabilitating refugees after Partition.

Booker Prize-winning novelist and activist, she arouses anger and admiration in equal measure. She famously declared herself an "independent mobile republic" to protest India’s 1998 nuclear tests. She is vociferous in her opposition to "market-is-god" globalisation and US policies, and like the best polemicists, allows no shades of grey, giving voice to ideas that are unfashionable and uncomfortable.

The only person on this list who wasn’t born an Indian but became one, Agnes Gonxha Bojaxhiu spent her life tending to people so sick and so poor that no one else wanted to look at them. Shamed, the world bore witness to her virtue, and heaped honours on her, including the Nobel Prize. Some, like Christopher Hitchens, made decent debating points about her proselytising motives and shady fund-raising, but Indians in general seemed to think that it was extraordinary that she bothered at all.

The title of his first novel, Swami and Friends, could serve as metaphor for the world of small-town India that Narayan Englished into fiction. Malgudi, the invented town in which his stories are set, is loosely based on Mysore, and is at once an idyll, another age and a persuasive stand-in for an everyday India. His novels, written in a plain style, are inimitable: he has no followers and, arguably, no equals.

It is statistically incredible that two brothers should make the list, it is even stranger that choosing Rasipuram Krishnaswamy Laxman alongside Rasipuram Krishnaswamy Narayan should seem inevitable. But then, Laxman is our greatest cartoonist and his Common Man pocket cartoon in the Times of India has been a national institution.

Through her novels and short stories, this prolific writer gave Urdu fiction a brave and endlessly inventive new voice. To quote the London Times, her magnum opus, Aag Ka Darya (River of Fire), "is to Urdu fiction what A Hundred Years of Solitude is to Hispanic literature. [She is] one of the world’s major living writers."

The first to be published of the new breed of Indian novelists flagged off by Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, Ghosh remains the most impressive. His work explores the historical connections between the Arab world, south-east Asia and the subcontinent. Neither parochial, nor possessed by a Naipaulian anxiety about the West, his fiction has a cosmopolitanism that chronicles Indian lives in their Asian arena.

His creative genius straddles many literary forms—from the historic sweep of novels like Sei Somoy and Pratham Alo (Those Days and First Light), set in the 19th century, to those reflecting complex turmoils, like Pratidwandi and Aranyer Din Ratri, both great Satyajit Ray films.

A pioneering historian of the Sikhs, the author of a fine novel about Partition, editor, memoirist, columnist and political naif, he is a man of many parts, but he’s here as the writer who invented himself: the hard-drinking, wise-cracking, godless sardar taking on hypocrisy.

Not just a great Kannada novelist, but an institution-builder who shaped cultural sensibilities to a larger worldview. He also wrote encyclopaedias, compiled lexicons, revived traditional dance-dramas like Yakshagana, all his work imbued with a spirit of scientific quest and a liberal humanism.

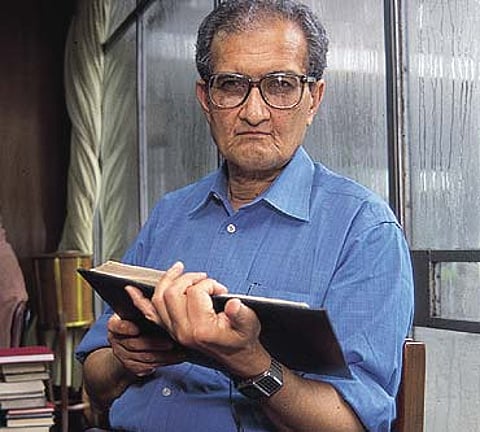

Bengal has a habit of producing world-historic Indians: Rabindranath Tagore, Satyajit Ray and now, Amartya Sen. His work on social choice theory, on the causes of famine, on ‘positive capability’ give him intellectual credentials respected by such disparate publications as the Wall Street Journal and the Economic and Political Weekly. Middle-class Indians know the geography of his resume by heart, from Drummond Professor, Oxford, to Nobel winner for Economics. The UPA government could have brought that resume home by making him President.

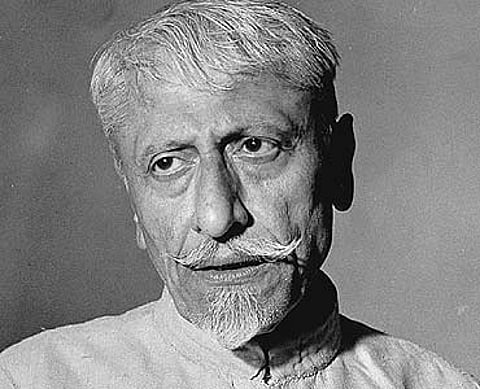

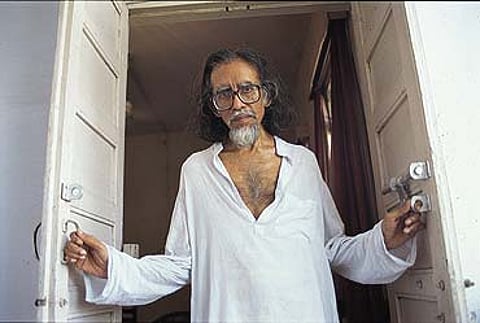

English-speaking readers know him as a grim, unsmiling acerbic cartoonist. For the rest, he was possibly Malayalam literature’s most potent and gifted novelist. Author of the astonishingly creative novel The Legends of Khasak, he set a "benchmark" for Malayalam writers. "For me," he said, "fiction can only be written in Malayalam, however unexposed the language is". Vijayan passed away in 2005, largely unmourned and unlamented.

One of India’s most influential playwrights, his work evokes social, political issues that are eternally relevant. Ghasiram Kotwal was set in the 18th century, but it found contemporary resonance at a time when the Shiv Sena was on the rise and the Emergency was round the corner. His Sakharam Binder, Ardh Satya, Manthan are immortal too.

One of his earliest plays, Tughlaq, a stupendous allegorical work on power, history and the complexities of the human psyche, was the first sign of a prodigious talent that was to express itself in many more plays, as well as in his acting and his courageous activism in support of all forms of freedom of expression.

The father of our ‘white revolution’, he represents another side of business—collective ownership and a bottom-up approach. His work in setting up dairy cooperatives empowered thousands of small farmers, gave them financial power, and helped make India one of the world’s biggest milk producers, with globally recognised brands like Amul.

His extraordinary rags-to-riches story epitomises the grit and dynamism of self-propelled Indian entrepreneurship. He is credited with having revolutionised the way our stockmarkets, financial markets and global-scale projects are run. A major influence on critical economic policies in the late 20th century, he also epitomised the growing nexus between business and politics.

India’s first business visionary, whose thinking went beyond toplines, bottomlines and marketshare. For this humane industrialist, who was a byword for business ethics and corporate philanthropy, social margins and national interests were vital.

Our first MNC promoter, he truly put India on the global economic map. He also transformed the way in which businessmen were perceived by the middle-class, intellectuals. His achievements and his business philosophy have encouraged thousands of conservative, educated, middle-class Indians to think big.

The most renowned living exponent of Kathak, he conjures up Lord Krishna’s mesmerising magic the moment he appears on stage. And he has as many talents as the Blue God had wives—musician, drummer and choreographer par excellence, including for films like Ray’s Shatranj ke Khiladi.

She was to Bharatanatyam what Pavlova was to ballet—a legend whose every movement was imbued with sublime grace and passion. A Devadasi dancer from Tanjore, she took classical dance out of the temple, bringing it to the public stage and international acclaim.

India’s answer to Picasso, he’s taught us a new way to look at everything from horses to goddesses. With his penchant for ambling around barefoot and chronicling his crushes on actresses on canvas, he’s the icon of modern Indian art, admired for his eccentricities and his moolah. Hindu extremists have chased him into exile, but most Indians hail him as a national treasure.

The artistic descendant of Indian mythological oleographs as well as Rousseau and Hockney, this iconoclastic, self-taught artist depicted Everyman in India with compelling and enduring power—whether in the midst of sectarian violence, in a roadside teashop, or in a homosexual relationship. His paintings continue to be sought after and prized by the world’s top museums and collectors.

Kapil Dev Nikhanj is Indian cricket’s greatest fast bowler, its best all-rounder and the captain who inspired a middling Indian side into winning the World Cup of 1983. Enough said. You know it all.

Our greatest batsman, he helped India defeat the West Indies in 1971 helmet-less, with the most prolific series debut in the history of Test cricket. When Indian batsmen were notoriously shy of fast bowling, he took on Windies quicks with classical poise.

He was just 19 when he won the Grand Master title in 1988, and he’s been on a winning spree ever since, claiming the world crown in 2000. The genial genius, whose unflappable exterior hides his quicksilver mind and razor-sharp analytical prowess, is now the reigning World No. 1 in the world chess federation’s rating.

India’s finest woman athlete, she dominated the Asian track scene in the ’80s, winning 33 medals, with 18 golds at the Asian Games and Asian Track and Field Meet. Named Asian Woman Athlete of the Year from ’84 to ’87, and again in ’89, she now trains those who aspire to follow in her fleet-footed steps at her athletics school in Kerala.

He symbolises the Golden Age of Indian hockey. As centre-forward, he was part of the team that won Olympic Golds in 1948, 1952 and 1956, and Asian Games Silvers in 1958 and 1962. He was also an inspired coach, who took India to World Cup victory in ’75.

Independent India’s first film icon, this consummate showman’s appeal captured audiences from China and Moscow to Cairo and Timbuktu—his cultural diplomacy for India was unparalleled. In the ’50s and ’60s, his roles projected a sense of idealism, hope and confidence, and the dream of bridging social, economic and political inequalities, something that struck a special chord in the newly independent nation.

The undisputed auteur, he took serious Indian cinema to the world stage. He broke new ground with the brilliant Pather Panchali, which was different from any film made before it, or after. Deeply rooted in India, yet dealing with themes of universal and enduring human concern, his films like the Apu trilogy, Charulata, Jalsaghar, Sonar Kella and Shatranj ke Khiladi remain classics, rediscovered with awe by every generation.

The tall, handsome superstar with that hypnotically deep voice became everybody’s favourite anti-hero in the ’70s and ’80s. As the Angry Young Man in films like Deewar and Zanjeer, he reflected society’s angst about growing corruption and violence. Not everybody cares for his new persona, as the marketeer’s dream ambassador for everything from cement to chocolate, but his iconic status endures.

He was that rare bird, an auteur who didn’t sing in an arthouse. Through the ’50s and early ’60s he used a repertory of talent—the most beautiful women (Madhubala, Waheeda Rehman, Meena Kumari), the best character actors (Johnny Walker, Rehman, Mehmood), genius lyricists, composers (Sahir, Kaifi, S.D. Burman), a great cameraman (V.K. Murthy), a brilliant writer (Abrar Alvi) and a remarkably plain leading man (himself) to make a string of melancholy classics.

It was the soaring notes of his shehnai that heralded the dawn of freedom on August 15 1947. His virtuosity raised the humble shehnai to classical status, but it was his spirit that made his music so sublime—worshipping both Allah and Saraswati as he did his daily riyaaz on the banks of the Ganga in Benares, he was a symbol of our composite culture, and the noblest ideals to which independent India aspires.

She was the unrivalled ghazal queen of India, with her earthy voice, captivating stage presence, and, above all, her ability to evoke romance, passion, wistful yearning, betrayal (but no self-pity, no regret). Those emotions came through so strong and true in each line she sang, because she’d lived them all in her chequered life, and survived to tell the tale.

Songbird, diva, prima donna, manipulator, monopolist. Her unparalleled reign over the world of Hindi film music attracted both adulation and controversy. But for several generations of Indians, right up to the ’80s, she was the indisputable voice of Hindi films. An entire nation, led by a prime minister, wept when she sang Aye mere watan ke logon.

Sarojini Naidu called her the Nightingale of India. Her music was an expression of her deeply spiritual personality, and touched to the core all those who heard her. She sang with equal sweetness in eight languages, and countless households all over India still begin their day on the right note with her Suprabhatam, her Meera Bhajans.

He began as a keyboard player in a Chennai band, and shot to fame with his music for the film Roja (1992). Now his inimitable brand of ‘Indian fusion’ music is a hit the world over, in shows like Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Bombay Dreams and Chinese film Warriors of Heaven and Earth. His Vande Mataram became the anthem for a young, upbeat generation.

He took Indian classical music out of baithaks and soirees into the public arena, and made classical Indian sitar an international craze, with admirers including the likes of Yehudi Menuhin and the Beatles. As purists raised eyebrows, he experimented boldly, collaborated widely, but never made the journey from popular to populist—his roots in the sitar’s classical traditions ran too deep.

Tags