Towards A Kinder Garten

Does corporal punishment leave a child disciplined or scarred?

Caned and Disabled

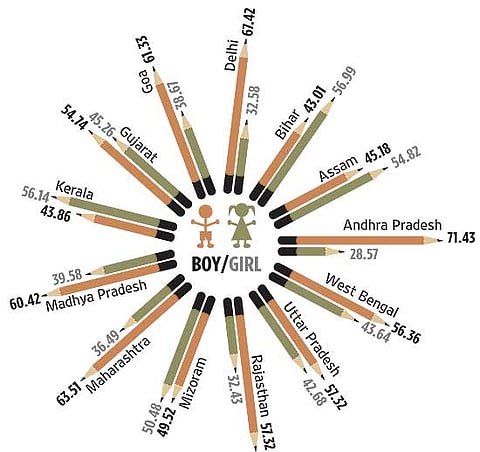

A 2007 survey by the WCD ministry shows boys get the wrong end of stick more than girls

All of us can recall, though not with fondness, the first stinging slap by the math teacher high on numbers and low on patience, or the first rap on the knuckles with a wooden ruler by the Hindi teacher or the first caning by the headmaster for sneaking out of school. What’s the din all about, you ask—specially in a country where child rights have never been the focus of a national discussion? And we are not talking hyperventilating TV-led debates where verdicts are delivered on SMSes.

Well, for one, though corporal punishment is a crime punishable by law, and two judgements—by the Delhi High Court in 2000 and by the Gujarat High Court in 2009—have expressly banned corporal punishment, it has taken the death of Rouvanjit Rawla, a Class VII student of La Martiniere School, Calcutta, to start a public debate on corporal punishment. What is also happening increasingly is that children are speaking up (see letters in box), confiding in their parents and word reaching lawyers, NGOs or constitutional authorities about the horrific stories of corporal punishment and abuse in schools.

Last year, when parents vociferously protested the fee hike imposed by schools in Delhi, teachers found a novel way to wreak vengeance on the children. Students of schools like the Vishal Bharti School, Paschim Vihar, were made to sit on the floor in the December winter. Poonam Choudhury, whose two children go to the same school, says, “The school found our children easy targets. One kid’s grades too were spoilt.” Poonam, a member of the Parent Teachers Association, confronted the principal, who denied everything. “As parents,” Poonam points out, “we just chase reputed schools to get our children admitted; once that’s done, we don’t care or bother to ask them about what they go through every day.”

Abject humiliation, if you ask Siddharth Nandi, a Class X student of DPS Calcutta. “I think caning is humiliating,” he says. “I would not want to show my face to the class if it had ever happened to me.” The worst punishment he has been subjected to was when he was asked to stand before the class for 15 minutes.

Having suffered humiliation in school himself, Manoj, a physically challenged parent, has vowed to bring to the attention of school authorities every single act of abuse—verbal or physical—committed by the teachers at St Peter’s Convent School, Vikaspuri, Delhi, where his son studies. “It is just not permissible to beat a child or abuse him,” says Manoj, who still bears the emotional scars of having his teachers call him not by his name but by alluding to his physically challenged status.

Manoj was subjected to what is now officially recognised as verbal abuse, and strictly prohibited by law. In fact, very little was known about the extent of physical or verbal abuse of a child till a national survey conducted by the department of Women and Child Development of the Government of India in 2007 lifted the lid off the crimes visited on school children in the name of punishment.

- In 2009, Shanno, a Class II student in a school in Bawana, Delhi, died of a heat stroke after she was made to squat in the sun.

- Last year, Punita Singh, mother of a Class III student at St John's High School, Chandigarh, complained to the state administration that a teacher had slapped her son several times. An inquiry found the teacher, Reema Talwar, guilty.

- This May, Indu Bala, principal of the Government Model Senior Secondary School, Sector 35, Chandigarh, slapped a Class XII student when she was talking to her friend during a free period. Bala, who was on deputation to Chandigarh from Haryana, was sent back to her parent cadre.

- In October 2009, two Class III children of St Joseph English Medium School in Mydukur, Kadapa, Andhra Pradesh, were found speaking in Telugu. They were forced to wear a slate around their neck, declaring ‘I will never speak in Telugu’.

- When a Class III teacher in a Hyderabad school hit a boy, his hand was so swollen that his parents took him for an X-ray which showed a fracture. The school just reprimanded the teacher.

- In Prakasam district in Andhra Pradesh, a bleeding child had to be rushed home after his teacher threw a duster at his head for talking in class. The teacher was suspended.

- Earlier this year, Somesh, studying in a prestigious private school in Bangalore, was humiliated and caned by his teacher for not bringing colour pencils to school. The teacher also asked Somesh's classmates to give him a rap on his thighs. Incidentally, it was the child's birthday.

- On June 19, Satish, a child from a government school in Chennapatna in Ramanagaram district, 60 km from Bangalore, was thrashed so harshly by a teacher that it left bruises on his hand and back. The teacher, Hemavathy, was suspended and arrested.

- A year ago, in a government school in Annehalli of Mulbagal taluk of Kolar district, Karnataka, his teacher beat Umesh so hard that he had to be treated at nimhans, Bangalore, and continues to feel traumatised. The teacher, thankfully, was suspended.

- In 2006, a Class VIII student from Guru Nanak High School, Sion Koliwada, Mumbai, died a day after being beaten and made to climb three flights of stairs on his knees for being late to school.

- A Class VIII student from St Francis High School, Vasai, Mumbai, was beaten with a metal ruler by a teacher for causing commotion. It left Nirmal with bruises on his upper back, shoulder and left arm and cuts on his forehead.

- In early 2008, eight-year-old Rohit Kumar Sakpal of Sangli, Maharashtra, was beaten to death by his headmaster.

- Last year, Tinha, a Class VII student at Little Angels High School, Sion, Mumbai, had to undergo humiliation because her hands had mehendi designs that she and her friends had done for Id. She was made to sit outside the principal's office on the floor facing a toilet for over six hours, for two successive days.

Based on the experiences of 12,447 children aged 5-18 years in 13 states and 2,449 stakeholders (adults holding positions in government departments, schools, private service and urban and rural local bodies, as well as individuals from the community), the study revealed a high prevalence of corporal punishment in all settings—family homes, schools, institutions and on the streets. Two out of three schoolchildren were found to be victims of corporal punishment, that is, an overwhelming majority of children (65.01 per cent) reported being beaten up in school. Of these, 54.28 per cent were boys and 45.72 per cent were girls (see infographic). The study also indicated that an alarmingly high percentage of children in state-run schools (53.8 per cent) faced corporal punishment, followed by public schools (22.3 per cent). NGO-run schools accounted for 13 per cent cases.

The most commonly reported punishment was being slapped or kicked (63.67 per cent), followed by being beaten with a stave or stick (31.31 per cent), and being pushed or shaken (5.02 per cent). Such punishment sometimes left visible marks, as in physical injury, swelling or bleeding. However, little gets known of the mental anguish a child goes through unless it manifests in a suicide or death. When stakeholders were asked for their views on physical/corporal punishment, over 44.54 per cent felt it was necessary in disciplining children, 25.45 per cent disagreed and 30.01 per cent expressed no opinion. Uday Nair was specifically asked his views on corporal punishment when he went to a Noida school where he wanted his son to study, and when he answered in the negative, was told that it was essential to discipline a child! His son was refused admission.

Confront teachers with the stats, and most of them deny ever having raised a hand on a child, though privately they will confide that a slap or two is an important aspect of disciplining. “The school principal is the godfather whom every child looks up to,” says a Delhi teacher. Some like Alex Mathew, who teaches English at St George’s Mount High School in Pathanamthitta, Kerala, actually believe that caning is unavoidable. “A small dose of pain helps in correcting a child,” he says. “But it should not be torture and a medium for the teacher to vent his anger. If the teacher canes to humiliate the child, the action would be counterproductive.”

Madhumita Ray, a teacher at Pratt Memorial School in Calcutta, whose daughters go to La Martiniere for Girls, says, “Some amount of disciplining is required and I think a teacher should be allowed the freedom to take punitive or disciplinary action. But it should not cross over to the category of abuse. The idea is not to humiliate the child or hurt him physically.”

But, faced with the staggering number of abused children in schools, what is the legal recourse in case of corporal punishment? Says social jurist Ashok Aggarwal, known for dragging every school that violates the dignity of a child to the courts and who also headed the two-member committee which enquired into the La Martiniere incident, “Unless the relevant sections of the IPC—namely Sections 88 and 89, which state that an act done in good faith for the benefit of child by the guardian not intended to cause death is permissible—are struck down, teachers and guardians will continue to enjoy immunity.” According to Aggarwal, the Right to Education Act (RTE) and several other guidelines are inadequate as deterrents. He recommends that the relevant ipc sections be amended.

“Corporal punishment,” says Isidore Phillips, director, Divya Disha, a group which works for child rights in Andhra Pradesh, “is just a case of teachers not knowing what to do when the child doesn’t listen. So they fall back on beating a child.” Teachers have to realise that child rights and dignity are non-negotiable.

It’s worse in the villages. S.S. Rajagopalan, an 80-year-old Chennai-based educationist, says that in cities at least “the parents come marching to the school to fight. In rural areas, parents accept corporal punishment because they feel that teachers beat children for a reason.” Rajagopalan spearheaded a campaign against corporal punishment after Ram Abhinav, a 16-year-old student of Velammal Matriculation School, committed suicide in 2003 after being caned for being absent. “Till today,” Rajagopalan says, “the management has not expressed regret.” Two years earlier, Thoufeeq, another student from the same school, had committed suicide.

“Corporal punishment is very common in Tamil Nadu,” asserts V. Vasanthi Devi, chairperson of the Institute of Human Rights Education and ex-chairperson of the State Commission for Women. “Because of the fierce competition, there is a ruthlessness in dealing with children. The problem is, parents don’t mind as they think this is the way to make children succeed.”

“Beating a child or abusing a child begins when a teacher’s intelligence does not match that of a child. It is simply a reflection of the teacher’s inadequacies who cannot motivate a child by making the subject interesting,” says Vasireddy Amarnath, who runs Slate The School in Mumbai. And it’s not just about the physical abuse. “Children in some schools are subjected to psychological abuse in the name of caste or physical appearance and called dark, ugly, fat or short by insensitive teachers.”

Scratch any child and umpteen tales of corporal punishment and abuse will emerge. But does the law have anything to punish the punishers? “We are looking at strengthening our laws,” says Shanta Sinha, chairperson of the National Committee for the Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR). As of now, it is learnt that the report the NCPCR prepared on the La Martiniere incident has been rejected by the school. Says Sinha, “Ours is a statutory body and what we say has to be taken seriously.”

As for any serious effort to sensitise teachers, most schools have no specific programme. Nina Nayak, chairperson, Karnataka State Commission for Protection of Child Rights, talks of one failed exercise in her state. “There was an effort about three months ago by the director of the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan in Karnataka to give government schoolteachers an orientation against corporal punishment. Interestingly, the teachers, I learn, were not receptive.”

How then does one compensate for the loss of life, limb or dignity of a child? New laws are certainly needed to make teachers more accountable. Our education system needs to move away from the Victorian-vintage dictum of ‘spare the rod and spoil the child’. Britain, which gave us both the proverb and some of moral/legal legitimacy accorded to it, has long banned corporal punishment and abuse.

By Anuradha Raman with Smruti Koppikar, Dola Mitra, Sugata Srinivasaraju, Pushpa Iyengar, Madhavi Tata and John Mary

Tags