Heavy mist covering the lush meadows, thundering waterfalls and pristine landscapes and an absolute lack of human population give this faraway land the appeal of an Impressionist painting in green and blue. With no insects or predators roaming the land and crystal-clear lakes defining the geography, this land is where surviving species were fairly few until some sea-faring voyagers stumbled upon it.

Land of the White Cloud: Exploring New Zealand's Maori Heritage

Maori heritage of New Zealand reflects in the Kiwi culture, ancient forest rituals and even the afterlife

They witnessed it from a distance, this island of mist, and named it Aotearoa, or the land of the long white cloud. These settlers were the Maoris, the indigenous tribe of New Zealand, whose careful stewardship of their land has preserved its natural beauty, and have ensured its purity and pristinity to date.

Since that time—approximately the 1200s—New Zealand has remained verdant as ever, though the mist has cleared considerably, and the land has now been occupied. According to popular belief, when the Europeans arrived, they named it Niew Zeeland, after New Sealand in Holland, another paradise of blue-green lakes and fields.

Even though it has become a full-fledged country with a remarkable presence on the global tourism map, the imprint of the Maori culture remains strong and weaves its way through myths and legends, ancient forest rituals, tattoo art, and even the afterlife. The Maoris felt a strong spiritual connection with the land and tended to it with devotion and by worshipping nature and all its elements. The Maori heritage is reflected everywhere—in the local cuisine, folklore, and even the bioluminescent paua shell jewelry—but nowhere is it more visible than at the Waitangi Treaty Grounds. This historic site is where the eponymous agreement between Maori Chiefs and the British Crown was signed, leading to the birth of New Zealand as a nation.

The sprawling estate is beautifully landscaped and the place is prided to be home to a massive 116-foot-long waka or canoe, exemplifying and reminiscing of the one in which the first Maoris arrived, led by their Chief Kupe. The wood-carving studio, state-of-the-art museum, and maori pou (carved wooden posts) pay silent homage to the rich indigenous culture.

***

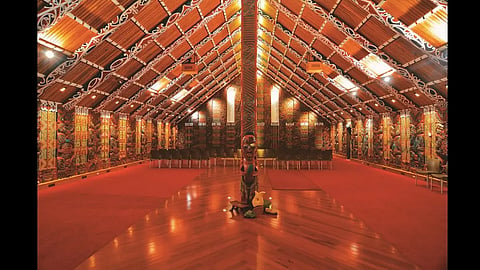

However, the true Maori spirit springs forth in the fiery welcome ceremony that feels more like a war dance with guttural cries, threatening looks, and brandishing of weapons. Once you enter the traditional hut or a wharenui, you can relax and enjoy a lively cultural performance, click photos with the dancers, and enjoy a mouth-watering meal cooked on a hangi or the earthen stove.

The northwest tip of New Zealand, jutting into the Pacific, is named Cape Reinga, which holds enormous significance for the Maoris. They say that the souls of the departed ones take a leap from here to start their voyage back to the ancestral homeland of Polynesia. It was prophesied that a great light would shine here someday—and sure enough, the lighthouse that stands here now guides ships to safety.

Another fascinating legend is the tale of Tane Mahuta, the forest God. It is a towering Kauri pine tree in Waipoua Rainforest that is a national treasure and is protected against insects, termites and any other possible threats. At 2,000 years it is believed to be as old as Jesus Christ himself.

The legend goes that Ranginui (Sky Father) and Papatuanuku (Earth Mother) were locked in a tight embrace for millions of years but their children were tired of the darkness, so Tane Mahuta being the strongest of them all, pushed his parents apart with his legs, thus flooding the world with light and life. When it rains, the Maori believe that it is Ranginui crying for his wife.

***

Elevated walkways lead the way to the majestic 148-foot-tall tree. Gazing up at it will give you a crick in the neck. The indigenous forest tour guide prepares a ‘Cocktail of the Forest’—made of three leaves of Kawa Kawa, a teaspoon of Manuka honey and boiling water. He then sings a stirring paean in front of the God, as members of the tour group raise a toast, and drink to his long life. It is a strange but, at the same time, moving ritual.

From herbal tattoo ink; made of mountain gum, fish oil, and burnt bark, to Manuka honey face packs and pounamu (jade) carvings, the Maoris’ rich legacy is closely interlinked with nature.

It is this ancient indigenous wisdom that lies at the core of taiki—taking care of culture—which is summed up in this saying:

He aha te mea nui o tea o?

(What is the most important thing in the world?)

He tangata, he tangata, he tangata

(It is people, it is people, it is people.)