Ever wondered how cities and countries all over the world, going back centuries, would have tried to protect themselves in cases of epidemics such as the plague?

Revisiting a Centuries-Old Quarantine Model in the Era of Omicron: The Cordon Sanitaire

The cordon sanitaire was a harsh but necessary intervention to save Europe from the threat of several epidemics. It may also save us from the spread of COVID-19

It shouldn’t surprise anyone to note that the governing authorities had their own measures and contingency plans if the spread of a disease went out of hand. If anything else, the quarantine models and norms were imposed far more strictly and were followed more rigorously than in the 21st century.

Enter the cordon sanitaire

In medical parlance, the cordon sanitaire refers to a designated bubble, usually between the borders of two countries, that is created around an area that is experiencing an outbreak of a disease. Once such a zone had been set up, no one could enter or leave the area. In its most extreme form, the cordon sanitaire was not lifted until the infection or disease itself was not eliminated completely. However, there have also been recorded cases of a reverse cordon sanitaire, where people in a particular region actively dissuade those outside from entering, in order to minimise the chances of a new infection making inroads into a population that may be susceptible to it.

However, this didn’t mean that cordon sanitaires were established at the drop of a hat. They were conceived possibly for the first time in the 16th century, an age when plague ran rampant all across Europe. Still, some conditions needed to be met before the cordon could be imposed:

- The infection was highly virulent and contagious.

- It had a high fatality rate.

- Treatment was difficult or non-existent.

- There were no means of vaccination or immunisation against the ailment.

Throughout the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, cordon sanitaires sprung up all across Europe and in the US mostly in response to plague outbreaks and a few instances of yellow fever—in Malta, England, Prussia, Scandinavia, Austria, among other places.

Why it was significant then—and is now

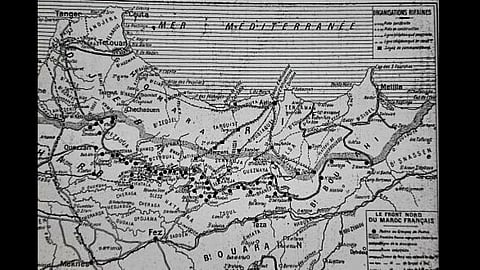

The cordon sanitaires assumed greater importance and, along with it, harsher, stricter forms from the 19th century onwards. This was driven, in large part, by the imperial ambitions of nations, especially in Europe, which exposed these nations to new germs and microbes in Asia and Africa. Rigorous cordon sanitaires were set up for all those coming from Asia and Africa from the end of the 18th century, and for some 50 years (and even after that), the rules were observed with utmost strictness to combat outbreaks of, primarily, cholera and yellow fever.

In an article for Ft.com, Paul Kreitman, an assistant professor of Japanese history at Columbia University, states that there were quarantine facilities for those crossing over via ships as well. Quarantine hotels called lazarettos were set up near harbours, while passengers could also be isolated and quarantined on board a ship. Kreitman points out one significant instance to explain why he terms cordon sanitaires of the 19th century as “the world’s first international travel bubble”. At the peak of the Napoleonic War, the British Navy lent ships to France which acted as “floating lazarettos” for French troops returning from Egypt, who would potentially have been carriers of bubonic plague.

Understandably, with the advances in modern medical science, many of the strict norms of a cordon sanitaire were bypassed for more relaxed conventions. However, with the bogey of the coronavirus in the 21st century, cordon sanitaires are making a comeback. After all, in a number of ways, the many variants of the COVID-19 virus that are still emerging fulfill the prerequisites for setting up cordon sanitaires.

According to Kreitman, the way cordon sanitaires were imposed in the 19th century has useful lessons for us in the modern day, regarding the setting up of uniform quarantine protocols. First, cordon sanitaires divided the world into health zones on the basis of how effectively the nation’s authorities were handling public health—something that is being seen in the COVID era as well. This division, however, did not affect the second much-needed lesson from 19th century cordon sanitaires: setting aside differences and achieving international cooperation between nations to set up quarantine and isolation procedures uniformly across the board. The third instructive lesson concerns the rigorous, “non-negotiable and mandatory” nature of the imposition of cordon sanitaires—in the 19th century, cordon sanitaires could last for as long as a month, with no option whatsoever for the people to “buy their way out”.

Irrespective of how harsh and outdated the norms may seem, cordon sanitaires make the case for the need to impose uniform measures with the cooperation of nations—a model or plan that could eliminate the possibility of double standards and glaring inconsistencies in the COVID management policies of respective nations, especially with regard to travel and tourism. Faced with an ever-mutating, fatal virus, that seems to be a small, but potentially life-saving, ‘sacrifice’ in comparison, doesn’t it?