Forty-eight winters, made up of months. Weeks. Days. But I remember only moments.

Moments that lie bunched together, like tightly packed reels of stored photo negatives in an old tin box. Always there at the back of the Godrej cupboard. Waiting to be rediscovered each time the box opens. Every disjointed moment held up to light is a reminder of all the days that I spent with you in this life.

I don’t want to miss even a single memory from those days. Especially the days that I can’t account for. The days that I don’t remember. The ones I want to replay but can’t recall. Those that instantly take me back to a faint smell of tobacco tinged with old Spice. Crisp geometric neck ties. An odd ring of words that made me laugh. By themselves, these flashes don’t mean anything, but then I remember that you embodied them. The tobacco and old spice. The geometric neckties. And those silly words you used to make up hilarious poems with. You — it was all you. The you that I don’t remember. The you from my childhood.

They say I was your darling. In winters, you would wrap me up and take me out of our overcrowded house for a gulp of fresh crisp winter air. Why can’t I recall those moments clearly? Does my love for winter gardens come from you because there are pictures of the botanical garden in the family photo album? Did you show me those butterflies hovering from one pink desi gulaab to another or did I just fix my gaze on that when you told me to look straight into the canon camera? Or maybe my love for winter sun is from you because it turns my limbs to jelly and my skin to water? Yes, maybe I sat with you aimlessly after lunch in the warm winter sun as a gurgling baby drifting into the deepest of sleeps on the charpai. My love for eating oranges and tender guavas in the quiet of post-winter lunch hours must come from you. The joy of inhaling the woody aroma of old books, page after page under the warmth of a heavy quilt is perhaps my inheritance from you. It’s so faint that I wonder if it is even mine.

Those winter days, those hours, those weeks, zilch. I do not remember those. I am left with just these lingering sweet nothings of images. Like an unremembered dream.

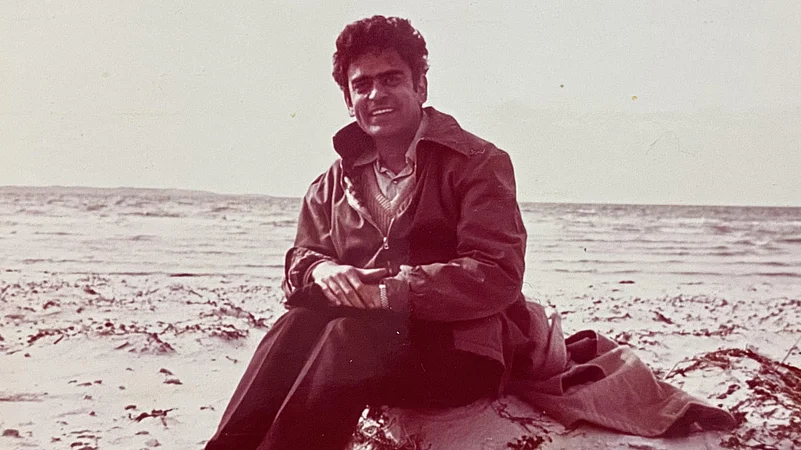

Sometimes when I can’t sleep, I open the stack of old albums that are embedded in my mind, trying to recollect that dream. I see a hazy impression of you. There you are, frozen in time in the winters that you did not spend with me. The handsome young man in a trench coat, in layers of clothing with smoke billowing out of his mouth, standing in deep snow — my Papa. An entire nameless account of the lost winters visible in your sharp eyes. The time when you went to study and work out of India.

I remember the letters, soaked in harsh and dark winter days, from Romania to India. Stamped and double stamped with ‘Air Mail’ printed across. How your hands must have shivered, the pen slipping from your cramped fingers time and again as you wrote to Mother — “Don’t worry about me Padma, I am fine, take care of yourself and the children, show them this picture that I am enclosing, tell them I love them, we will be together soon”. You must have asked a friend to take that picture, bought stamps on your way from your extra job at the supermarket, remembered to buy more envelopes on the way back from your institute. You must have written that letter sitting alone in your room at the youth hostel, after dinner, you must have walked quickly to drop the letter in a post-box. A post box that must have glinted in the darkest of snowy winter nights, where the sun disappears by 4.30 PM. The snow crunching and swooshing under your feet. Far from the warmth of the winter sun of home.

In those six winters that were stolen from me as you walked back and forth from the post office, the ‘Air Mail’ had remained a consistent reminder of you, often bringing a photograph or two of a cheerful face that I was told was my father’s. That face that travelled from the winter in one country to the winter in another and got tucked safely in Mother’s cupboard, in the tin box with all those photo negatives I assume.

I remember only the winters. I wonder why? Maybe because I remember wanting to be with you in those snow-clad pictures, longing to be geographically in the same place with you in the frosted land that the letters came from. But not being able to fathom the distance I gave up, and as young children often do — forgot about the whole thing entirely as time passed. Hopeful that maybe you would arrive one day, just as quickly as you had left. That’s what they said to me. Every time I threw a faint tantrum or had to be mollycoddled into doing something, your mythical presence was successfully invoked by one and all at home.

Well, arrive you did, on the cusp of a faint winter night at the Delhi International airport. The unmistakable nip of an oncoming winter visible in the air of late October of the year 1979.

I remember that evening. The line of foreign nationals gushing out of the airport late in the night was fascinating at first and chaotic afterwards. Mother had dressed brother and me in our fanciest best. Everyone in the family was so excited to meet you, except me. I was upset that we had to travel all the way late in the night to receive the man from the pictures, who seemed to be always dressed in eternal winter clothes. I had forgotten you completely. I was already asleep by the time your plane landed but vaguely aware of the familiar shoulder that carried me to the car. I woke up briefly to steal a heavy-lidded look at your face from my slumber. It was the same face — familiar but different. Older. Thicker. As I snuggled back into that woollen suit-clad shoulder, I could get a faint smell of the tobacco mixed with Old Spice. It felt like home.

Maybe that’s why winters feel so safe to me. Just like your shoulders that carried me. Where I could bury all my fears and go limp, knowing that I will only be put down inside a warm quilt that waited for me somewhere. And that I will wake up to a brand-new beautiful day where the sun shone in the garden after every cold night. That I will find you there. Reading the paper, drinking your tea, smoking your cigarettes.

All my years since that winter of 1979 have passed knowing that your shoulder will always be there. Steady, as a rock, safe as a hug.

The winter of 2020 was our last together. I came to see you and Mother after being away for a year during the first wave of Covid-19. I did not know it then, but I would stay till the summer of 2021, straight into the second and the deadliest wave of the Delta strain. I would spend many irreplaceable days with you walking around our university campus, doing mundane chores like buying groceries from the local shop, listening to music at night with scotch glowing in our glass, talking about books, films, sharing stories from your past, and my present. Later, eating dinner cooked by Mother, you and I together, and sleeping the soundest sleep that one can get only in one’s home. Time felt snug and so real, like a comfortable pair of old socks — warm and fuzzy.

Time began to shrink suddenly when, eventually, you ended up contracting the virus. I had to hide your tobacco, and use your Old Spice to prick your fingers to check your blood sugar numerous times a day. I ended up having to face my biggest fears, all alone, under curfew, locked down, with a smell of dying bodies all around me.

As you shivered in the hospital with the virus-induced fever, breathing laboriously, I tucked you with double quilts and a hot water bag, dark fear lingering above the room like thick black soot. Even though summer was only just approaching, you kept telling me to make the AC cold. Really cold. Like winter cold. And when you put your head on my shoulder on our last ride to the hospital, you asked for cold water, winter cold. When I rushed to the ICU the next day in panic hearing that you had gone into cardiac arrest, you had begun to grow cold. No matter how much warmth I tried to give you, you were cold. As cold as a snowflake. As cold as ice. As cold as winter.

The summer declared its onslaught as the sun rose relentlessly high above on the afternoon of your passing, mocking me mercilessly. Grief-stricken and heartbroken, I longed for the safety of the winter sun like I have never ever before.

After watching the blazing fires turn your body to ashes, I began to think about all the winters I had missed spending with you. I thought about all the missed winters I was never ever going to have or can ever catch up on. I suddenly felt abandoned, like you had hopped on to a long and never-ending flight once again and forgotten to take me with you. It would be much longer than the six winters that I can’t seem to recall. If we ever were to meet again. The unlikelihood of ever seeing you again tore at my eyelids.

There was no coming back from where you had gone — there will be no Air Mail, no pictures, no eyes looking back at me, assuring me that you will be back. I knew that I had to finally grow up and stop waiting. You will not arrive. I had lost you. Forty-eight years of my life that have been your gift to me seem to have flown past so quickly. All accounts of the days you didn’t spend with me now lay suspended in a vacuum, like ashes in the cremation ground.

So, on the cusp of this winter, I summoned up some courage and travelled back home to our quaint little hometown. To the desi gulaab. To butterflies. To the gentle aroma of books long forgotten in your bookcase. To your leftover ashtrays that smell of tobacco. To oranges and guavas. To the bottle of Old Spice still in your bathroom closet. I stood in anticipation as the familiar cool winter air brushed my face. Six months had passed since you had left. I had to compose myself and start giving away all your things. You had gone, and things are just things, they aren’t people, you always said that. I had made up my mind.

I took a deep breath and opened your cupboard full of winter clothes. Your hats. Suits. Jackets. Sweaters. Socks. And your Trench coat.

Right at the back, there it was. The beige Trench coat from the stolen winters. So many pictures that you had sent us had you wearing that coat. All the memories and images came rushing back to me instantly. Every picture that you had taken posing in the Trench coat on the streets of your university. Every letter that you had sent. Every person that you were. Every story that you had ever shared.

You see, that’s what you had done, you had filled those missing years with the stories of your experiences from those years. Stories that you had told me repeatedly. About how the streets looked; how the people dressed; who your friends were; how many trains you had changed to travel across Europe; where you ate; what you ate; the music you listened to; the films you watched; the books you read; how you walked in the snow; where you took the pictures that you sent us; who took them, and how long, lonely, trying and darksome nights of those six years were for you.

You had breadcrumbed the missing moments into your stories all along. You had kept the Trench coat, hoping perhaps that someday I will claim it and remember the stories you told with such passion and panache. That you had not forgotten that there was an account.

The hardest thing was to remove the coat from the hanger but just as I was removing it, my 17-year-old son walked up to me. He stood quietly next to me, watching me hold on to the coat with all my might and sobbing into it. He gently took the coat away from my fingers and slipped into it. It fitted him perfectly. The shoulders, the snug pockets, the lapels. Suddenly, the energy in the room changed, I couldn’t help but be amazed through my tears. This boy of mine who used to hold onto your finger and walk on his wobbly legs was now wearing the coat you wore as a young man. Playfully, the son dug his hands deep inside the coat and twirled around for me as I watched through the haze. He opened his arms, hugged me tight and whispered to me — “Mama, every time you miss your Papa you can hug me.” Overcome, I rested my head on his shoulder, feeling held instead by you.

The trench coat needs to be darned and dry cleaned; it has a few tobacco stains, a coin buried somewhere inside, but it is now hanging in the son’s cupboard in my Bengaluru home. I open the cupboard many times during the day, it is always there. Diligently present, standing in for you. The son saunters into my room from time to time wearing it, modelling your style. It always makes me smile. I know that the coat is not you, but I feel that there is you in there somewhere.

The presence of your Trench coat in my life makes me think that I will finally be able to reclaim some of those stolen winters and that I may even be able to welcome the summer sun when it arrives this year.

(Roohi Dixit is an award-winning Indian filmmaker, screenwriter, and director who started her filmmaking journey in advertising. In her 18 years of experience, she has written, produced, and directed films across genres under the banner of her production house, Zero Rules. Roohi dreams in technicolour. She is a daughter of university professors who are avid cinema lovers; storytelling runs in her DNA. Spaces Between, her last experimental documentary premiered at the IFFI festival in Goa and DFWSAFF Festival in Dallas. Roohi has also produced and directed the critically acclaimed documentary, Scattered Windows, Connected Doors. It won the Audience Choice award at the Mumbai International Women’s film Festival and the Best Documentary award at VISAFF (Vancouver International South Asian Film Festival). Roohi’s creative expression leans towards existentialism and resilience. She believes in the power of hope in the face of strife. Twitter: @RoohiD. Views expressed in this article are personal and may not necessarily reflect the views of Outlook Magazine)