Late 1930s. Medical College, Calcutta. At the students’ annual function, two scenes from Shakespeare’s mixed-race tragedy Othello are to be performed by Clayton and Rina, Anglo-Indian students who were dating each other. But just before the anointed time, Clayton vanishes, and the ‘mantle of the Moor’ falls on his classmate, the debonair ‘native’ Krishnendu, someone Rina had grown to particularly dislike. What happens during the play is unexpected and insurgent. Through Othello’s harrowing confrontation of Desdemona’s ‘disloyalty’, her equally fearless defence, his impetuous smothering of her, the inconsolable self-loathing, and his dolorous self-stabbing, Rina and Krishnendu (Uttam Kumar) fall suddenly, inexplicably but immeasurably in love.

This is Ajoy Kar’s Soptopodi (Seven Steps, 1961). The interpolation of Othello’s crisis of miscegenation becomes the symbolic crux in a film about mixed-race romance and the epic exertions of star-crossed lovers to attain union. Remarkable for its resplendent cinematography, sharp editing, use of war footage, minimalist soundtrack, the interplay of the personal with the political, and the unsurpassable chemistry of its lead pair, Soptopodi turns out to be an unforgettable romance. But perhaps its most enduring legacy is Rina Brown (Suchitra Sen in one of her defining roles), the luminous, self-assured, mannered Eurasian lady who studies medicine, steels herself at the revelation of her own mixed-race origins and displays exceptional fortitude in the face of love’s excruciating rewards.

But Rina is usually invisible to an eager tendency of sweepingly dismissing representation of Anglo-Indians in Indian cinema. Such a claim is understandable but also contestable. If one looks closely at how Hindi cinema has manufactured an apparent fictional, acultural trope for its protagonists (both male and female), representation of any specific cultural trope has mostly collapsed into archetypes: the geeky Bengali, the bumbling Sikh, the pious Muslim, the accented Tamilian, the servile Gorkha, and the booze-soaked Goan. For the last one, the odds are even worse: as Shoma A. Chatterji writes, “Indian cinema has reduced the Christian minority in India to a convenient monolith—a homogenous entity that does away with their ethnic divisions —Indian Christians, Roman Catholic, East Indian, Anglo-Indian, Syrian Christians, et al.” Chatterji also lists a range of archetypes that have perpetuated the entire church-going community—as being boozers, English-spewing henchmen, simpletons and railway drivers if men; and vamps, red-haired moles, dumb typists and liberally distributing sexual favours, if women. Given these overt and casual ghettoising and the overall narrative purpose of communities in Indian popular cinema, Anglo-Indians have not suffered any particular prejudice.

Moreover, there is more than just a handful of Anglo-Indian representations. One of the earlier films is Bhowani Junction (1956), George Cukor’s Hollywood romance, adapted from John Master’s eponymous novel. Though dated, there is that unmissable symbolism about Victoria Jones (Ava Gardner—ashen, eroticised), a Eurasian Madame Bovary embodying the ambivalence native to her community, torn as she is between childhood sweetheart Patrick Taylor (Bill Travers) and British army officer Colonel Savage (Stewart Granger). This is as potent for a romance film as it could be, and is as attentive to the cultural nuances as is Passage to India, which is to say, hardly at all.

But things have gotten better since. Julie (1975) was a breakout film about an Anglo Indian family’s alienation in a country steeped in tradition. Shyam Benegal’s Junoon (1979), historicised the vulnerability of a community forever divided about its Indian origins and its British proximity; something that becomes a personal crisis of belonging in Pradip Kishen’s Massey Sahib (1985). Both Junoon and Massey Sahib are also highly accomplished as works of cinema, and handle the cultural intonations with sensitivity. In fact, by focussing on minorities comparatively invisibilised in popular cinema, both these films (along with Vijaya Mehta’s Pestonjee, 1988) seemed to be living up to one of the founding principles of the New Wave, which was to look for cinematic subject in uncharted spaces. Less accomplished, both as film and as a cultural trope, is Anjan Dutt’s Bada Din (1998), and Bow Barracks Forever (2004). They are half-hearted attempts to empathetically indulge in the eccentricities apparently inherent in the community, Calcutta being the forbearing proscenium of this play. Similarly, Anglo-Indianness is merely a ploy for aesthetic overplay in Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Black (2005), the Helen Keller inspired biopic that liberally borrowed from The Miracle Worker (1962).

Aparna Sen, through 36, Chowringhee Lane (1981) caught the New Wave by its tail and made, perhaps, the most remembered film about Anglo-Indians. Sen’s early films are full of indignation against the selfish middle-class, her debut, 36, Chowringhee Lane being an unflinching examination of how easily they abandon those who have grown fond of (and slightly dependent on) them. Jennifer Kendall not only made Violet Stoneham a living presence but her portrayal of the aging, lonely, Shakespeare-loving Anglo-Indian spinster is so utterly memorable that it is perhaps impossible to better it ever. In terms of handling her subject with discernment, Sen’s most near kin, since Chowringhee Lane, would be her own daughter Konkona Sen Sharma, whose debut Death in the Gunj (2016) was set in the Anglo-Indian colony of McCluskieganj. Unlike Chowringhee Lane and Massey Sahib, Gunj is not a character study of Anglo-Indians. It is rather how, in a small hilly town made famous by the community and that which carries more ghosts of them than the living, the sensitive, undemanding, lonely Shutu is abandoned in a process of a symbolic (and historic) formation of majoritarian bonding. The film’s title and Shutu’s ghost that bookends the narrative, epitomises how McCluskieganj, as a site of Anglo-Indian home-making, has been systematically dismembered.

McCluskieganj was founded in the 1930s for a purpose but the city that has organically been the site of Anglo-Indian survivalism is Calcutta. No wonder Bengali cinema has portrayed Anglo-Indians in several wonderful instances. Vicky Redwood’s portrayal of Edith Simmons in Satyajit Ray’s Mahanagar (The Big City, 1963) comes to mind immediately. Redwood not only carried the empathy that Ray reserved for his key characters but her character was also an acknowledgment that the first women in India to have ever gone out in search of work, and have done so with unwavering spirit have been the Anglo-Indians, a spirit that guides the film’s lower-middle class protagonist Arati (Madhabi Mukherjee). The other example is Marco Polo (Utpal Dutt), the cuckolded disciplinarian but lovable manager of the fictional Shahjahan Hotel in Pinaki Mukherjee’s Chowringhee (1968), another bonafide classic of Bengali popular cinema, and adapted from Sankar’s novel, a Bengali classic. Jhor (Storm, 1979), the biopic of Henry Vivian Derozio, the pioneering 19th century Anglo-Indian reformer and rebel is poor cinema but did carry an important social message.

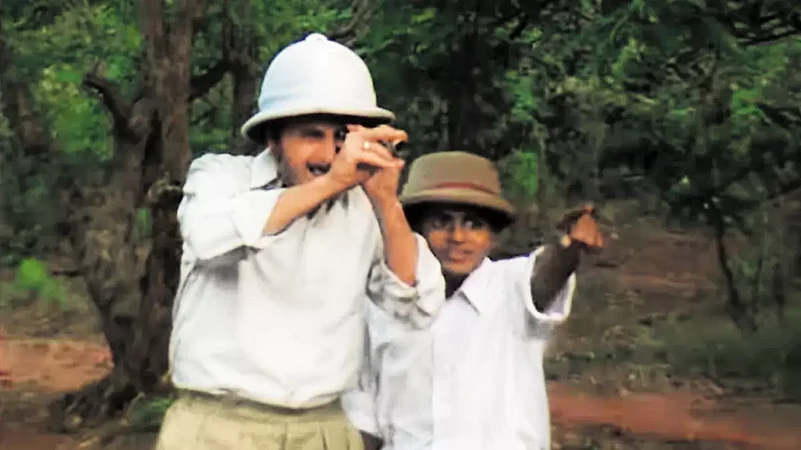

The film that should ideally conclude this piece is Antony Firingee (Poet from Another Land, 1967) which shares an organic bond with Soptopodi. It is loosely based on Hansman Antony, a Portuguese-origin, mixed-race poet, who, in the late 18th to early 19th century, made a name for himself in present-day Chandannagar, a former French colony. The happy-go-lucky, dapper musician Antony (Uttam Kumar) embraces the Bengali language, composes songs and tests his luck with kobigan—an impromptu, freewheeling poetry competition involving banter and wordplay. He also falls in love with the courtesan Nirupama (Tanuja). They bond over music, finding a companionship that could transcend the limits of both identity and provincial authority. But their union is disapproved by the Hindu orthodoxy who resent the happiness of people they consider heathen, their purposeful villainy leading to an inconsolable calamity. Sunil Banerjee’s fabulous musical manages to go well beyond the artless pulls of historical accuracy, preferring to stay in the domain of fiction, elevating a folksy tale of an angelic bard, his companion and their trial in a wretched land to a compelling cinematic tragedy.

Both Soptopodi and Antony Firingee play on the artistic possibilities of the archetype of embattled lovers trying to find union while also being superlative specimens of romantic melodrama. But more importantly, both films were and still are a sort of memorial to an alternative emotional history of cosmopolitanism and interfaith love, while partaking, many decades ago, in the bequests of modernity. From where we stand, the two films are hence metaphors for increasingly endangered ideas in a country tethered to xenophobia. That both of them have unforgettable Eurasian portrayals at their heart does carry immense cultural and cinematic gravitas.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Of Love and Longing")

(Views expressed are personal)

Sayandeb Chowdhury is an assistant professor at the school of letters, Ambedkar University of Delhi