Perennially on the hunt for a lasting and bankable hit formula, Bollywood is shuffling through time to make historicals and quasi-historicals. While some of these periodicals are realistic, others are purely apocryphal, with filmmakers occasionally locking horns over the same plot from the near and distant past.

With run-of-the-mill flicks faltering at the box office left, right and centre, nostalgia is the new staple in B-town these days. Little-known tales of the triumph of human will in the face of enormous adversity, buried for long in the annals of history or in the dusty archives of old newspapers, are being lapped up by top stars desperate to get out of the formulaic rut in keeping with the changing taste of a millennial-audience.

From the exploits of a phalanx of intrepid Sikh soldiers in a war against the marauding Afghans towards the fag end of the 19th century, to a saga of grit and adventure woven around the 1998 nuclear test at Pokhran almost a century later, dramatic episodes from bygone eras are being chronicled fast and furiously on celluloid now.

This week’s big release, Milan Luthria’s Baadshaho, is set during Emergency in the mid-seventies. The Ajay Devgn-starrer has drawn heavily from an ‘event’ wildly speculated about—an army raid on the Jaigarh fort in Jaipur to dig out a treasure trove, rumoured to have been buried there since the time of Sawai Man Singh, the trusted Rajput general of Mughal emperor Akbar. The raid against the former Jaipur monarchy, rumoured to have been undertaken by the troops at the directive of the then prime minister Indira Gandhi, is apparently the inspiration behind the plot.

A historic-fiction set during the Emergency which has characters going after a truck full of royal treasure

No claim to verity, though: the movie is being promoted as a fictional thriller involving six “badass” characters on the trail of an armoured military truck carrying gold worth crores of rupees through its 600-kilometre journey spread over four days. “The movie is definitely set in the Emergency but it is purely fictional,” says the scriptwriter of Baadshaho, Rajat Arora. “We had heard of one particular episode from that period but we do not even know whether that was true or not.”

Arora, who has written blockbusters such as Once Upon A Time in Mumbaai, The Dirty Picture, Kick and Gabbar is Back, admits that an incident hidden in the pages of history invariably makes for an interesting plot idea. “We normally get swayed by outside influence, especially from the West, in spite of the fact that we have an enormous amount of our own stories waiting to be retold,” says the 42-year-old scenarist who had also written Azhar (2016), the biopic of cricketer Mohammed Azharuddin. “Such stories are replete with the requisite twists and turns. And it is always fun to work on them because they are connected to us and our culture.”

Arora, however, points out that making historicals is not a new phenomenon in the industry per se. “Many great historicals and semi-historicals such as Mughal-e-Azam (1960) have been made in the past. The trend had stopped for some years, but now films like Bajirao Mastani (2014) and Padmavati (still in the making) are being made all over again,” he says. “Ultimately, what matters is not the genre but the entertainment quotient of a film.”

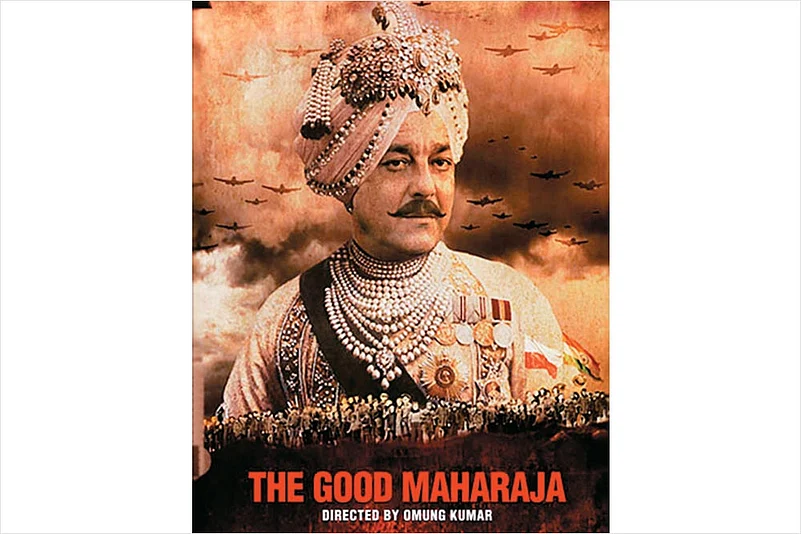

But then, such is the surge in the demand for historicals that often the same plot is tempting more than one producer. Omung Kumar, Mary Kom’s (2014) director, has already unveiled the poster of his next film, The Good Maharaja, with Sunjay Dutt playing the eponymous role of Maharaja Jam Sahib Digvijaysinhji Ranjitsinhji, the erstwhile ruler of the princely state of Nawanagar. And he is not alone—Ashutosh Gowariker is already in the process of making a film on the same king. What has, of course, prompted two prominent film-makers to work on the same subject is the extraordinary life of the Maharaja, who had provided shelter to 640 abandoned Polish children during the World War II.

One of the three films being made on the Battle of Saragarhi between 21 Sikhs and an Afghan army

This is, however, not the solitary plot to have spurred a race among filmmakers. At least three stars or directors have evinced interest in the Battle of Saragarhi, which was fought between 21 Sikh soldiers and a 10,000-strong Afghan tribal army way back in 1897. Sensing tremendous potential in the war story, Ajay Devgn was the first to announce a film, Sons of Sardaar, by releasing its poster last year. It was revealed shortly afterwards that Karan Johar and Salman Khan had also collaborated to produce a film on the same theme with Akshay Kumar in the lead. Though the Dabangg star is said to have withdrawn from the project since then because of his “good friend” Devgn, Akshay and Johar are all set to make Kesar on the same theme. Interestingly, away from this high-profile scuffle for Saragarhi, director Raj Kumar Santoshi is also quietly working on a similar plot with Randeep Hooda.

Conflicts around common interests are not new in the cut-throat world of tinsel town. “Altogether five movies were made on Bhagat Singh about the same time 15 years ago,” recalls veteran trade analyst Atul Mohan. “This usually happens because the audience has an abiding interest in the historical characters and episodes,” he says. “Cinema is such a strong medium to entertain and enlighten that audiences easily relate to historicals. After all, everybody has read a bit of history in their school days.”

A biopic in which actor Satinder Sartaaj plays Maharaja Duleep Singh, the last ruler of Punjab, who had to be taken to England at the age of fifteen

But history can be a contentious topic. Mohan, editor of Complete Cinema cautions the film-makers against distorting history in the name of cinematic licence. “Many of them take liberties with the facts. It should not happen beyond a point,” he says. Several film-makers whose recent releases were based on true events have been accused precisely of that. Madhur Bhandarkar chose to mix facts with fiction liberally in his recent release Indu Sarkar, which was also set against the Emergency, only to meet with widespread protests by Congressmen who accused the National Award-winning director of inaccurate portrayals of Indira Gandhi and her son, Sanjay Gandhi, in the film.

The descendants of Maharaja Duleep Singh also moved the Delhi High Court against the makers of The Black Prince, a multilingual biopic directed by Kavi Raj on the last emperor of the Sikh kingdom of Lahore, accusing them of having misrepresented the character of the 19th century king. Gurinder Chadha, of Bend It Like Beckham (2002) fame, also had her fair share of brickbats when she tried to take a fresh look at the Partition in Viceroy’s House, a historical drama set in the last days of the British in India, which was released last month in Hindi as 1947: Partition. Nonetheless, controversies or lawsuits have seldom deterred film-makers. Take for instance Sanjay Leela Bhansali, whose next historical, Padmavati, elicited violent protests during its shooting in Jaipur earlier this year.

Experts believe that the rise in the number of movies of a particular genre reflects nothing but the herd mentality of the film fraternity. Akshaye Rathi, leading distributor-exhibitor, says that chances of the audiences connecting to a historical portrayed in a dramatic way is slightly better than other genres, but what they actually need is a judicious mix of different types of films. “The problem is that when a Dabangg or a Singham becomes a blockbuster, everybody else in the industry too starts making action-oriented dramas,” he adds. “And when Kal Ho Na Ho (2003) hits the bullseye, the audience gets inundated with NRI-centric ventures. Similar is the case with historicals.”

The story of the film is woven around India’s second nuclear test near the town of Pokhran, Rajasthan, in 1998

As of now, contemporary history is increasingly proving to be a rich site for film-makers to choose from. John Abraham’s latest ongoing project is a film called Parmanu; The Pokhran Story, based on India’s nuclear test near Rajasthan’s desert town in 1998. This is Abraham’s second tryst with a realistic modern-day historical. In 2013, he came up with Madras Café, tackling the unusual theme of Indian intervention in strife-torn Sri Lanka in the 1980s, which subsequently led to the assassination of former prime minister Rajiv Gandhi by LTTE activists. This year, The Ghazi Attack, co-produced by Karan Johar, was inspired by true events about the destruction of a Pakistani submarine by the Indian navy during the 1971 Bangladesh war.

Film writer Vinod Anupam, however, says it would be a fallacy to believe that Bollywood has veered towards realistic cinema through historicals after junking formula films. “We as a nation are very fond of nostalgia and that is why the film industry is picking historical themes. It is also choosing less-heard stories about the struggles of the common man, but every plot still has to fit into its own old formula,” he says.

Aka Viceroy’s House, the film tells a story from the last days of the British Raj in India

Anupam says Bollywood could simultaneously make five movies on Bhagat Singh because the story contained ‘action’, but it fights shy of making a film on Gandhi or an Ambedkar, whose lives are thought to be devoid of the twists and turns required for commercial cinema. “It takes Richard Attenborough to make a film on Gandhi’s simplicity,” he adds.

The national award-winning writer further says that Bollywood has been forced to look out for real incident-based themes because the audience has started rejecting its hackneyed plots. “But it is not right to say that the film industry has dumped its template for masala flicks altogether. Bollywood is still not ready to believe that a Bareilly ki Barfi (2017) could be a hit movie. It is also yet to come up with another Queen (2014) in the past four years,” he points out.