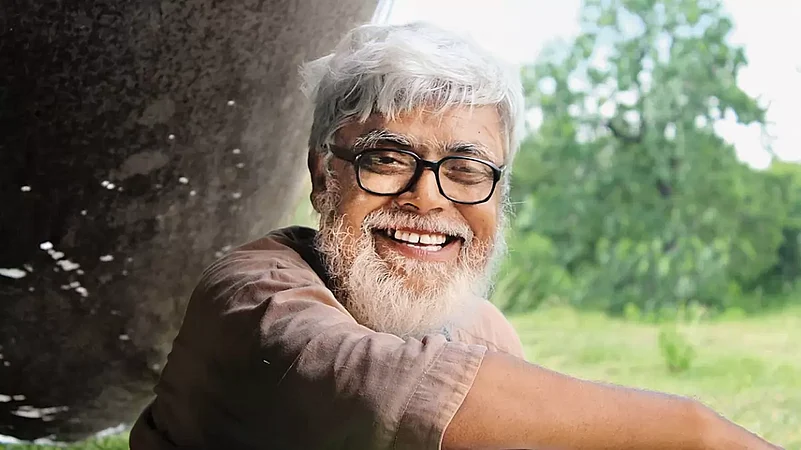

Meghnath, the director of nationally and internationally recognised documentary films like Naachi se Baanchi, Gadi Lohardaga Mail and Kora Rajee, discusses how films and music have acted as weapons of resistance for Adivasis. Along with Biju Toppo, Meghnath has been working in Jharkhand for more than four decades. The author of ‘Gaon Chorab Naahi’, a song that has turned out to be an anthem for people’s struggles across the country, recounts his work among the Adivasis of the Hindi belt to Outlook’s Abhik Bhattacharya

In the long history of Adivasi struggles, we have read how culture has been taken up as a strong weapon of resistance. In your five decades’ long experience both as a social and cultural activist, how do you find it resonating on the ground?

Truly, in the history of Adivasi struggles, songs and folklore have been consistent components. If we look at the songs together, we can understand it with much clarity. In the Netarhat struggle, where people fought for more than 30 years against dispossession and displacement against an effort to convert a huge area into field firing range for the Army, use of the songs of resistance were visibly prevalent.

In Oraon language, there is a phrase “Bijay Bighul Kharkha Lagi” that means ‘Bighul has trumped and it’s time to get ready for the move’. We collected all those local folksongs and phrases and came up with an audio cassette. That helped the people’s struggle a lot. We made it around 25-30 years back. However, it still works today.

ALSO READ: The Adivasi World: One With The Earth

What drove you to take up such initiatives? How do you think music and lyrics work as forces of resistance?

Actually, our major motto was to re-hash their own songs that talk about their people, stories and struggles so that they can feel proud of it. That was even the reason for us to form ‘AKHRA’. ‘Akhra’ is similar to ‘chaupal’ where in Northern India people sit for a chitchat. ‘Akhra’ is its Mundari version. In the centre of the village, this is the space where people come, sing, dance, share their thoughts, struggles and discuss issues of significance that affect their lives.

Dr. Ram Dayal Munda gave the name Akhra to our organisation. As I said, it helped us to give strength to the struggles of Netarhat. Later, our song ‘Gaon Chorab Naahi’ became the resistance song for people’s struggles across the country.

To make it further clear how music works, let me talk about another film that we made entitled Kora Rajee. It is on the tea plantation labourers of Assam who mostly belong to this region (Chhota Nagpur). They have been working there for more than 150 years. Though this is a documentary film that had won international awards, it was mainly focused on the lyrics. The spine of the film is the songs of the tea garden labourers.

In contrast to the market forces that have commodified music, how are you retaining cultural authenticity?

To respond to this, I must refer to the film that we made entitled Gadi Lohardaga Mail. It was produced in this context. During the 1990s, so many music albums were coming up in the market across Bihar, Jharkhand, Bengal, Chhattisgarh. Those were just made for dances, copying Bollywood films. Sometimes, it was even below one’s dignity to see all those dances.

So, Dr. Ram Dayal Munda told me, “Meghnath, can we not see our thing with respect and dignity?” Then the idea cropped up and we made the film. It is just a collection of good songs sung during a train journey. Until now, we have made three films on three major festivals of Jharkhand: Sohrai, Karam and Sarhul. We made it for the coming generations so that they remember their rich culture.

These films talk about the meaning of the festival so that it is celebrated keeping its authenticity intact. For example, let me tell you a story. Sohrai is celebrated to thank cattle. Now where did it come from? As per the folk legend, their God, Baba Thakur, sent his ‘gorait’ (informer) to tell the people that they should take shower thrice and eat once a day. But the informer on the way messed it up and told people that they should take a shower once and eat thrice. Now Baba Thakur said, “If people will take food thrice a day, our capacity of cultivation needs to be increased.” And thus, he sent the informer as cattle to help the people.

Such stories will resonate among the youth and will help them to be guided by their legends. Like this, Karam and Sarhul also have rich content and our efforts were to bring it to the public.

What do you think about the continuous devaluation of Adivasi culture in different spheres? How might it be confronted?

Look, this idea of superior and inferior cultures comes out of our colonial mindset. There is hardly any work being done on the Adivasi values in the Hindi belt. But in the northeast, we can find some significant works. We have used films, music and other modern technologies to spread our message.

Tell us a little more about Akhra.

You see, I am basically a social worker. I have been working in films for the last 30 years but prior to that, for more than two decades, I worked as a social activist. During this period, I found that intellectual works among Adivasis were mostly unexplored. Then, Dr. Ramdayal Munda and I felt that we need to work on the intellectual production and Akhra was formed in 1992-93.

We received support of several youth from colleges and Biju Toppo (an internationally acclaimed filmmaker who works with Meghnath) is one of them who stayed till now. There were several Adivasi intellectual youth who extended their support and thus we have been successfully producing documentaries for almost 30 years now.

During your productions of the documentaries, have you found Adivasis getting engaged? What is the connection that they feel?

Let me tell you first why we chose to make documentaries. Both the fiction and documentary communicate but the former needs support of several departments and for the latter, it is all about the living subject. People need not act here; it is real to the core. You can make a standard documentary with a reasonable budget.

In theoretical terms, the father of the documentary, John Grierson, says, “Documentary is the creative interpretation of actuality.” We embarked with basic skills of camera and other technicalities to communicate. So, people participate in whatever way possible. And we take our films to the people on whom they are made.

As what we make is connected to their lives, people sit down and watch the films with great interest. We have gone to places where around 5,000 people sat and engaged with the film, even skipping their dinner.

It is a blatant lie that the people don’t want to see serious documentaries. If it is on an issue that touches their lives, they will definitely see it. Our film Naachi se Baanchi on Dr. Ram Dayal Munda has received a captivating response as wherever we took it, people watched it without a break.

In the last five decades, we have seen a sort of Hinduisation of Adivasis. What is your take on this? What do you think about ‘Sarna Dharma’?

‘Sarna Dharma’ is a fragment word of the bigger thing that is known as ‘Adivasi Dharma.’ Dr. Ramdayal Munda called it ‘Adi Dharma’. I personally feel that Adivasis have a different kind of religiosity and that is totally different from the belief systems of Hinduism, Islam or Christianity.

In ‘Adivasi Dharma,’ there is no idea of hell and heaven, no reincarnation. Unlike Hindus, Adivasis don’t have any ritual of ‘Shraadh’; they call back the spirits home to guide them. This ritual is called ‘Ghar Bhitri’. Adivasis across India have their own beliefs.

But politics is also connected to religion. Those who held power, from the Britishers to the Mughals, all tried to impose their religion on the Adivasis. Now, those in power are trying to do the same and they are being called Hindus.

But the original religion of Adivasis does not have any connection to Hinduism.

In these years, what sort of change did you notice on the ground?

I have been here in Jharkhand for more than 40 years. And earlier, when we used to visit Adivasi villages, we never saw so many Hanuman temples, Shiv Mandir etc. RSS-BJP have been working their propaganda. We communists used to believe that those who till are the owners of the land. And here, they have worked on the ground and now are reaping the fruits. Dr. Ram Dayal Munda used to say, “If Adivasis believe in their own system, they will not be colonised.” Otherwise, we are giving in to the colonial powers.

What is your advice to young Adivasi filmmakers?

With the democratisation of technology, film-making has now become much easier. I appeal to young Adivasi filmmakers to uphold their own rich culture instead of emulating Bollywood or Hollywood films. We have enough constituents to explore and celebrate our ideals. We must proceed in that direction.

(This appeared in the print edition as "A Music Of Resistance")