He swirls and soars high above in the sky, in a blood-red flowing robe, to throbbing, pulsating music, his sinews taut, his eyes dreamy, every cell in his body in motion. Mohammad dances like a man possessed with the sky as his stage. This is his fantasy world. In real, Mohammed is a Syrian crane operator at a construction site in Lebanon, like hundreds of others in punishing, inhuman conditions. The stunning 15-minute short film Warsha by Lebanese filmmaker Dania Bdier, a Sundance prizewinner and festival favourite since its release in 2022 explores the lives of Syrians in Lebanon and the ravages of war. In an exclusive interview, Bdier talks about how all films from the Arab world are political. Edited excertps:

You were born to Syrian parents and grew up in Beirut. How does this heritage influence your work?

My parents are Syrian and my culture is Syrian. My grandmother, my uncle, cousins used to live there. But we grew up in Beirut so it’s more like home for me. But Syria is a big part of our culture, our cuisine, our humour. I also had the Syrian accent myself. Because of the political issues between Lebanon and Syria, kids at school used to make fun of my Syrian accent. So I chose to get rid of it and only have a Lebanese accent. Lebanon is a country where I spent most of my formative years, that’s where I became an activist. So I am very aware about the relationship between the two countries, about what it means to be a Syrian in Lebanon. Construction workers in Lebanon are primarily Syrian migrants who work as cheap labour. I wanted to bring in that feeling of being not exactly at home.

At first, you wanted to be an actress?

So yes, at first I wanted to be an actress. But at 15, my father gifted me a video camera. That changed everything for me. It was a mini DV camera and I started filming everything around me with it. I taught myself editing. I was basically that person in the group who used to film everything and make little edits out of our outings. I watched a lot of television and movies and I realised everything I was filming was very different from the stuff I was watching. I became really interested in wanting to capture those untold stories, in capturing the complexities and nuances of growing up in this part of the world and trying to stop being represented by others telling our stories. So that is when I decided to be a filmmaker.

You visited many construction sites for depicting a crane worker for Warsha. Why a crane worker?

I wanted to tell the story of a man working at a construction site after I first saw a man praying on top of a construction crane. So I started visiting construction sites. The people I was interviewing would always tell me that the crane operator was always living in his own bubble. He arrives in the morning with the rest of his co-workers but he climbs the ladder and stays up there all day and doesn’t interact with his fellow workers. So there is total isolation, or privacy or freedom or loneliness—however you want to see it. But when I was at a construction site, there were three elements that I was very aware of.

One, it was a very male dominated space. I was the only woman on the site and it was very noticeable. Second, it’s a very loud, cacophonic space. So it’s the kind of place that makes it very difficult to hear yourself think let alone dream. Third was the fact that all the workers there were Syrian. They didn’t have full time contracts and were primarily working on daily wages. There was a very stark difference between the Syrian workers and the Lebanese engineers. The site allowed me to see how the crane operator is the only one who gets insulated from all this.

Gender fluidity is the central theme of your film…

I wanted to make a film about a crane operator but I didn’t know the story yet. I just knew that the crane operator is going to be seeking the privacy of this cabin. While the film was cooking in my head, there was a new song that came out by an artist named Khansa. I loved the music video and I loved the song. I went to see him live and it was a transcendental performance. He blended gender in such an interesting way, alternating between the feminine and the masculine in a hypnotic way. You are just seeing beauty and art. Khansa and I became friends and I discussed this film with him about a crane operator, what can he be seeking in the privacy of that cabin. Since we both had a huge attraction for the art of drag and loved watching drag queens, we brainstormed the idea that what if this crane driver wanted to express his inner drag queen? That is when we decided Khansa was going to play the role of Mohammad. I learnt that he also specialises in aerial stunts. So we decided even the cabin is not going to fit Mohammad and his ambitions and that he is going to explode out of the cabin and perform off the tip of the crane for anybody to see his art.

Warsha is also a political film...

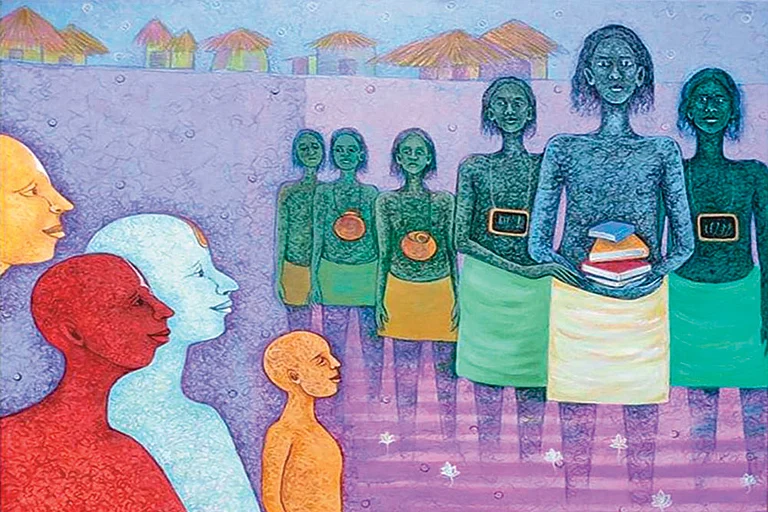

I don’t know if I would define Warsha as a political film but then in some way every film is political, or at least all my films or films set in the Arab world. They are rooted in the context of the country and with that comes the socio-political and economic issues of the region. So in my film there is definitely some politics, I touch on the life of migrants. I also touch on the racism that exists between neighbouring countries. The third thing I touch upon is gender norms because they are very strict in the Arab world. I wanted to break open this question of why can’t a crane operator have his own dreams? Who decided that singing and dancing belong to the female gender only?

What is the symbolism of the red-coloured robes?

Well, Mohammad’s character is very introverted, he is almost invisible. He doesn’t want to call attention to himself because he is a Syrian migrant worker. But within his migrant worker community, he has a secret desire and a passion that he is not comfortable expressing. So he cannot fully actualise his true self. If he cannot show his true self he would rather just blend in. The opposite of that is the colour red. It is the loudest colour. It demands the most attention. And secretly, his dream is to be seen, is to be celebrated for his performance, as and artist, as a creator, as a performer.

Do you think Arab women are creating a new space for themselves in contemporary cinema to tell stories that were so far neglected?

Yes, I think Arabs in general are attempting to create a space for themselves in contemporary cinema. The West tended to tell the stories of Arabs from their perspective. So I think in general, Arabs are now telling their own stories but they are mostly men. So when women start telling their own stories as well then it gives us an opportunity to see things from our point of view. There are certain issues and experiences very specific to women and they can relate with women across the Arab world and women all around the world as well. I’m not saying a man can’t tell a woman’s story or an American can’t tell an Arab’s story but there’s always more truth when it’s coming from the person themselves. So it is a welcome change that at least Arabs are telling their own stories.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Sputnik DREAMS")