All his life, Vempati Ravi Shankar used to be extremely proud of his heritage as member of a family that has been synonymous with one of India’s eight classical dances. Only three days ago had the Kuchipudi master vented his frustration openly over how the integrity of master-teacher relations were getting diluted in the art that gained huge popularity in the last century owing to tenacious efforts of his legendary teacher-father Vempati Chinna Satyam.

On January 20, Ravi Shankar sought to “raise my disappointment and concern on how the guru-shishya parampara is being taken very casually these days”, by taking exception to mindless alterations in the choreography of Vempati compositions. “It takes years of experience, knowledge and hard work” for such dance compositions to form shape, he noted in a Facebook post that further said, tampering with them can “in no way be justified if the same is represented as a Vempati composition with no essence in it.”

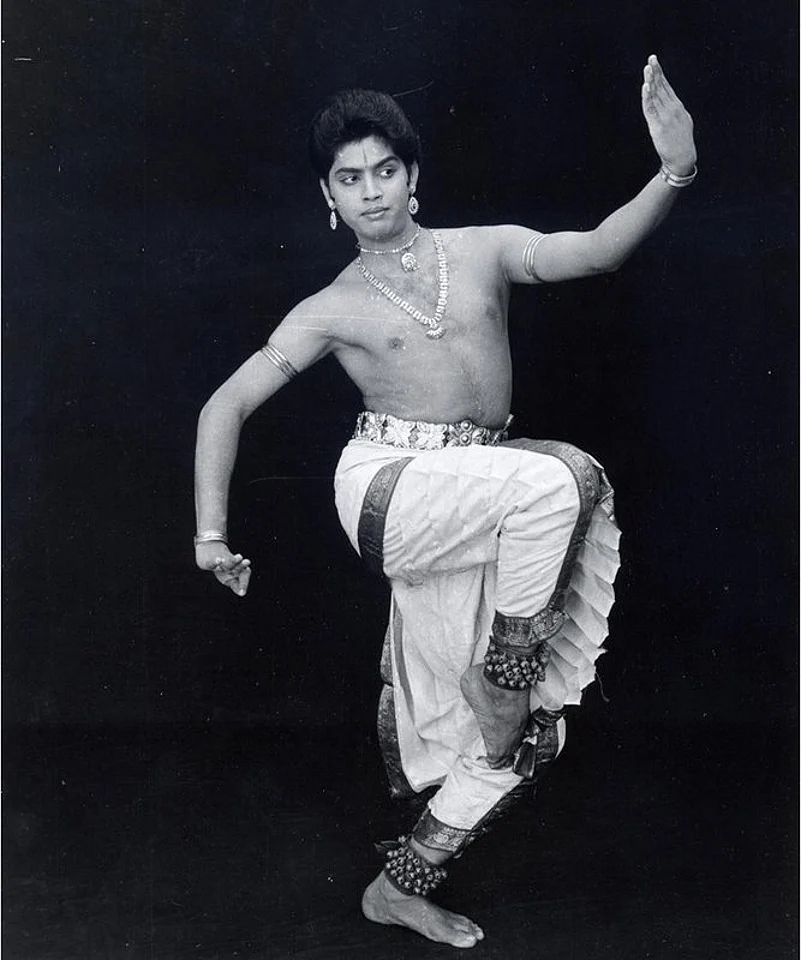

Ravi Shankar had for over three decades embodied the next-generation spirit of Kuchipudi—a performing art that has its roots in a medieval village by the same name in present-day Andhra Pradesh. Only 48, he died in Hyderabad on January 23 following a cardiac arrest.

It was a tragic end to a cultural pilgrimage that began when little Ravi was a child. For, even before actually getting initiated into the form, he used to watch his father giving disciples pre-dawn classes in a closed chamber that had a hole through which the boy used to peep for hours together after waking early from sleep.

“In our tradition, the Vempatis are very particular that the Kuchipudi attire is adhered to strictly and it is definitely expected out of our students too,” he notes in the social-media message that turned out to be his farewell to the followers. “Every student is made aware of this while they learn under our tutelage.” The classroom culture expected “regular communication with the guru” so as to “definitely result in the right amount of reviews and re-evaluation of the compositions on how they would be represented by the student,” he adds.

Ravi Shankar was born six years after his father had set up the Kuchipudi Art Academy in Chennai (or Madras, as it was called then) in 1963. Two decades prior to it, the country was a couple of years short of attaining independence when mid-teen Chinna Satyam (1929-2012) had reached the Tamil city. It was by walking all the way from his native Kuchipudi, 40 km off Vijayawada in what is Krishna district of Andhra Pradesh today. That trip also marked the start of a new chapter of embellishment to the millennium-old dance that had experienced a round of renaissance in the 17th century.

“It was a great privilege to be born to a great maestro, but my father never wanted me to take up dancing as a profession,” Ravi Shankar later tells a dance critic in Kerala. Sensing the disenchantment with the young boy for whom dance was a passion even at the age of five, Bala Kondala Rao, one of the senior disciples of Chinna Sathyam, took him under her wings, points out the scholar, Irinjalakuda-based George S. Paul, in a 2006 write-up.

Interestingly, that training went on for ten years—and all that while without the boy’s father knowing of it. Eventually, on a Vijaya Dashami day, Bala showed her guru the performance of his son—but the master gave a muted response, which disillusioned the boy. However, to Ravi Shankar’s joy, he soon learned that Chinna Sathyam had found the boy’s dance techniques perfect and that the top guru chose to be silent because he was against the “syndrome” of masters promoting their children often out of the way.

Ravi Shankar was to soon get trained systematically under his father as well. That began showing results: for a decade from 1994, he danced almost all major characters in the Kuchipudi repertoire that found stages as productions by the academy. The young artiste used to constantly speak of Kuchipudi as primarily a male-centric form, which did welcome woman dancers who also excelled in the art in the 20th century.

Even so, Ravi Shankar used to be critical of overzealous practitioners turning Kuchipudi into “acrobatics of sorts”, where the pot-on-the-head item was being presented, sometimes with the dancer holding lamps too. That way, he had strong opinions about certain “distasteful” trends in the art he held so close to his chest. One was about tutorship. “Though, by experience, we have seen it takes as long as a decade of learning under a guru to imbibe the lineage, it is expected that a minimum of four years of training is required, before they pursue their future on their own as students of the guru—so as to be addressed as his disciple,” he noted.

In fact, Ravi Shankar’s swansong FB post ends thus: “With all that said, my sole intention here is to preserve this great art form of Kuchipudi, with its own identity, essence and beauty. I have done the same all through my life and will continue the same, with the blessings from the Lord Almighty.”

God, as most simple-hearted Indians would say in the death of a young soul, has called him to his abode early.

.jpg?w=801&auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&format=webp&dpr=1.0)