As performers, practitioners and teachers of Bharatanatyam, it is crucial for us to understand the historical and socio-political context of the dance form. Bharatanatyam’s history is not uncomplicated as it is often made out to be—as if it were an ancient, unbroken and pure tradition untouched by colonialism and post-colonial nationalism. In fact, what it was before the onset of colonialism, in the hands of the original masters, the devadasis, and what it eventually became as it passed through a socio-political prism—the evolving idea of a newly independent India—are arguably two very different dance forms. Sure, they shadow and echo one another, but they are distinct in terms of their relationships with the body and sexuality, their narrative content, the spaces in which they are performed and the very dancers who practise, perform and teach them.

Nehru, within the rubric of ‘unity in diversity’, sought to appreciate and acknowledge regional, religious and sub-cultural identities, but he also envisioned a strong, unified nation that would ultimately transcend these smaller identities to evolve into one pan-Indian identity. In the cultural sphere, those in the nationalist movement who considered themselves custodians of art interpreted this to mean finding one pan-Indian national dance form. This dance form was Bharatanatyam. But it could not become India’s national dance in the form it existed in pre-colonial times. Colonisers made an example out of the Devadasis and their dance to demonstrate the sexually unrestrained and barbaric nature of the natives, creating a sense of shame in Indians. Revivalists and nationalists, therefore, felt impelled to transform both the dance and the dancer in order to make it fit its new ‘national’ role. The result is now widely known.

The nationalist-revivalist visionaries set out to suppress erotica and sensuality, focusing instead on devotion (thereby ‘sanitising’ the form); make Bharatanatyam available to ‘good Brahmin girls’ (i.e. not Devadasis); take it out of temples and onto proscenium stages; and institutionalise its pedagogy (establishing Kalakshetra and formalising dance education). Thus, what was actually in India’s dance tradition was thoroughly morphed in this modern secular-nationalist reformulation.

Those who represented the Devadasi’s Sadir fiercely opposed these transformations. But in that transformative air of newly independent India, the change came with the force of an idea whose time had come.

What resulted was an arguably modernist version of the Devadasi’s Sadir, a dance form that belonged not to the Isai Vellalar community of Devadasis, but to what the nationalists saw as a wider spectrum of practitioners comprising Brahmin ‘girls of good families’, and performed not in temples, but in ‘secular’ spaces accessible to a more diverse audience. It also tilted favourably towards ‘devotionalism’—possibly seen in line with patriotism and nationalism—and away from questions about the body and sexuality, now seen as shameful and best avoided.

Over half a century later, practitioners are often asked how they feel about the history of the dance form. When I learnt of Bharatanatyam’s tumultuous and complex history, I was fascinated, but also felt derailed. My idea of this flawless dance form became somewhat tainted. While my love for it never dwindled, I felt betrayed by the ‘lie’ that resulted from the post-colonial reimagination of Bharatanatyam—the idea that the Devadasi era was a brief, unfortunate and corrupting hiccup in an otherwise pure history. But, had it not been for the post-colonial revivalist movement, the dance form would never have been accessible to me. There are indeed many facets of that transformation that I deeply respect, such as the structure and codification of technique, and I have retained many of these facets in my practice and creative expression. Yet, I could not allow myself to be blindly and dogmatically devoted to the form.

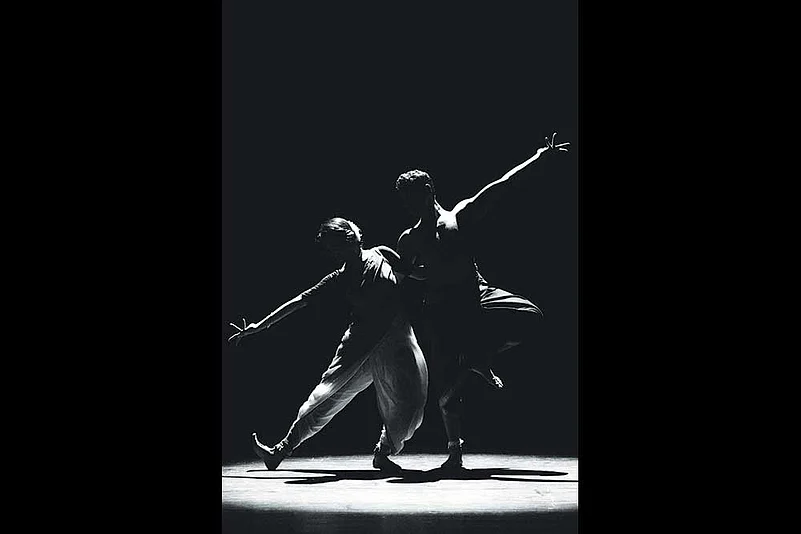

As I grew confident as a dancer and choreographer, I found my own creative expression in Vyuti, my dance company, through which I chose to deal with some of the bones I had to pick with the ‘nationalised’ dance form I had devoted myself to for over two decades. I wanted to challenge the ways in which classical dance deals with the body and direct physicality. As a solo dance form, it managed to circumvent this almost entirely since there is no other body on stage to physically touch. Even in dance dramas, the touch and even eye contact is largely superficial, not real. But Vyuti’s work is all about touch—physical and visceral touch between multiple and interweaving dancers. The dancers interlock arms, put their arms around each other, hold hands, lean on one another, and even share each other’s weight—lifting each other off the ground. At the very least, they look directly into each other’s eyes, acknowledging each other and honouring the idea of intimately sharing a vulnerable space—the stage.

Re-situating the dance from a temple setting to a proscenium theatre, too, had implications on the form—significantly, the introduction of a singular front where the dancer is on stage, facing an audience in front of him or her. The proscenium, unlike the proximity between dancer and audience that the temple allows, creates a formal distance between performer and spectator, which compromises some interaction between them. In my practice, I attempted to examine how the singular front changed dance and recreated how dance may have been viewed in pre-colonial times.

Using alternative spaces, Vyuti’s work invites audiences to sit closer to and all around the performers, enabling audiences to view the work closely from multiple angles and challenging the dancers to be aware of the audience in more than one direction.

Vyuti’s work also removes itself from the sringara-bhakti binary through its narrative content. Sakhi, Vyuti’s sole narrative piece, is about female friendship. Neither sringara nor bhakti, yet it has elements of both. In one instance, the female protagonist reminisces about erotic and intimate moments with her lover to her friend; in another, they discuss the lover’s devotion towards the nayika. Dealing with emotions and human interactions, it is far removed from the religious, mythological and devotional narratives dominating classical dance.

Vyuti’s second narrative piece, currently in its nascent stages, is based on kama. This piece rebels more boldly against the post-colonial nationalist rejection of the erotic by directly addressing it through Vyuti’s corporeal technique and interweaving vocabulary. As a practitioner of Bharatanatyam, I find myself constantly negotiating with its nationalisation. I respect, adhere to and adore some elements of its post-colonial form, even as I seek to question and challenge others like the touch taboo, erasure of the Devadasi’s imprint, and rejection of the sensual and the erotic. The constant negotiation between Bharatanatyam’s pre-colonial past and post-colonial present is essential to me as a practitioner of this beautiful and complex dance form, a bearer of its tradition and a living example of its evolving modernity.