It’s after the interval, and the story has taken an unforeseen turn…. The usual arc of a Hindi film never holds too many surprises. What it affords you is the comfort of the familiar—plotlines unfold within a kind of permitted range of variability. But now, come to the last year of the Tenties, think of Hindi cinema itself as one large film, and imagine that what we’d seen in the past was only the first half…. It’s clear that, in the second half, we have moved into a strangely new landscape, touched by a new kind of human presence, peopled by real people, not just an Adonis here and a bevy of apsaras there. It’s a massive churn: like Bollywood’s genetic code itself is being rewritten. Stereotypes are being thrown out of the window, fixed formulas turned on their heads, the beaten track studiously skirted. And yet, all this is unforeseen only in relation to our old habits. The change is actually quite organic, and was perhaps inevitable. The old Hindi film had run its course, played its part in our social history. What the world’s largest film industry is undergoing these days is a makeover quite in sync with the changing times.

And the vanguard of this revolution, carrying the seeds of something that looks set to alter the rules of the game for good, is a motley group of young actor-stars. To begin with, they look different. While quite personable, they are not the marble statuary of old, nor the testosterone-turbocharged alpha male. And they are daringly different in their approach to the whole craft of cinema acting, in their choice of roles and how they choose to embody the characters they play. A Lothario’s sex appeal will never quite be out of fashion, but it’s also the kind of man these actors represent. More believable, as if made out of real clay, and not afraid to be vulnerable on screen. An Ayushmann Khurrana still totes those washboard abs in a film like AndhaDhun, but he’s no superhero, just that cute, secretive guy who lives upstairs.

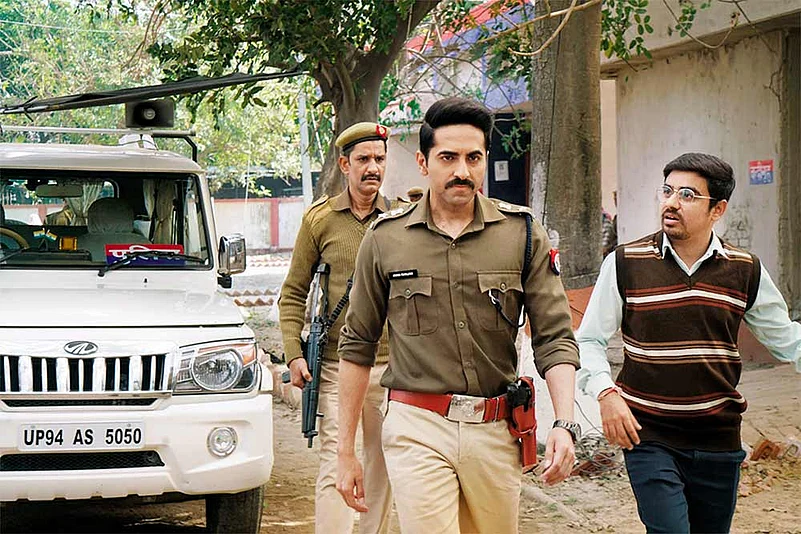

Nor are any of them built in that old antihero mould, moping around in grey noirish shadows. Check only the weekend bustle and hum at the multiplex turnstiles. Khurrana, Vicky Kaushal, Rajkummar Rao and many others of their ilk are proving their acting mojo, yes, but also pulling in some of Bollywood’s biggest box-office successes—that too at a time when cinema is facing a challenge from new platforms. Khurrana has just struck gold again with Article 15, revolving around the prickly subject of caste. It would have been unthinkable a decade ago for a mainstream hit to be woven around that theme, but the film opened to rave reviews and good collections.

For the uninitiated, Article 15 is the Chandigarh-born Ayushmann’s fifth consecutive hit in a row after Bareilly Ki Barfi and Shubh Mangal Saavdhan (both 2017), AndhaDhun and Badhaai Ho (2018), a feat none of his contemporaries have managed to pull off so far. Article 15 does two things: it underlines, yet again, the 34-year-old actor’s knack for picking fresh, offbeat, even risky stories, as also his talent for crafting viable hits (along with a new set of directors) out of what may have been indie curios at another time. “Article 15 is an incredibly important film for India and its youth and I’m delighted with the love and appreciation it has received,” he tells Outlook. “As an actor, I have backed a story that’s tremendously relevant and I thank my director (Anubhav Sinha) for his brilliant vision and courage to tell a story that needed to be told.”

He plays an IPS officer sent off on a punishment posting to a rural boondocks, where he soon finds himself trying to crack the gangrape and killing of Dalit girls, very reminiscent of the infamous Badaun case of 2014. An emotionally draining role, he admits, but he’s “overjoyed” his work is being liked and that audiences “want to see good, quality cinema” (see “Good content can never go out of fashion”). Drawing stories from contemporary reality isn’t exactly an old Bollywood habit, so that’s one facet of how the industry is maturing. And Ayushmann’s understated police officer is a far cry from the deliberately over-the-top Chulbul Pandey of Dabangg (2009), revelling in a faux rusticity.

But Ayushmann, like his millennial peers, is loath to follow the old herd. He in fact seems to sniff out exactly what may have been anathema for older heroes. Ever since he debuted in Shoojit Sircar’s Vicky Donor (2012), a wacky entertainer about sperm donation, he has consistently pushed boundaries as an actor, choosing one quirky character after another. In Shubh Mangal Saavdhan, he played a married man grappling with erectile dysfunction, and in Badhaai Ho, his first Rs 100-crore hit, he was a young chap left acutely embarrassed by the pregnancy of his elderly mother. Name one actor from the past who would have touched such themes and characters even with a bargepole.

The Article 15 director puts it down to more than risk appetite. “Ayushmann is one of those rare actors who’s more interested in the film in its entirety, its story and intent, than just the character,” says Sinha. “There’s no actor when he sees the character. He just steps away and becomes the character so beautifully and effortlessly that you no longer see Ayushmann, you only see the character.” Sinha, who made the critically acclaimed Mulk last year, says this degree of immersion in the story’s frame is rare. “It’s his biggest strength. His second biggest strength is that he does not take his success seriously at all, forget very seriously.” Somehow, you tend to see that as a natural corollary of the kind of man you see on screen: naturally quirky and winsome, but the vibe is almost self-effacing, not self-aggrandising. That pretty much dismantles the idea of the Bollywood superstar, whether built in tragedy king, towering inferno or beefcake mould. But Ayushmann isn’t a solitary mould-breaker, standing aloof from his generation. Rather, he’s typical of it.

Anybody who saw Masaan four years ago had no doubt that he was only biding for his ticket to stardom. Sanju, Raazi and Uri made him a formidable force in this era of content. He has signed many interesting movies, including biopics of Udham Singh and Gen Manekshaw..

Take Vicky Kaushal. Five years ago, you wouldn’t have heard the name. And then only in little ripples along the edges. But now, he’s another striking candidate to fill out the new kind of hero—fully-formed as an actor, full of an offbeat brio, but buzzing right there on centrestage. And how. After a stunning debut in Neeraj Ghaywan’s Masaan (2015), he earned his spurs in the marquee of big guns with Sanju and Raazi (both 2018) and, above all, the monster hit Uri: The Surgical Strike, smasher of many box-office records in 2019.

For Vicky, it was all too surreal. As he tells Outlook, nobody had expected it (see “I surrender myself to the director’s vision”). But Uri, with a collection of nearly Rs 250 crore in the domestic circuit alone, is now tenth on the list of Hindi cinema’s highest grossers. And the line “How’s the josh?” became a meme. Vicky had tasted mainstream success with Sanju and Raazi before, but Uri came as an ultimate validation. Of the actor, as well as of a new template. A blockbuster without a superstar…nothing catches the zeitgeist better than that.

Many other small-budget movies have done astounding business of late. Ayushmann’s Badhaai Ho and AndhaDhun, for example, garnered worldwide collections of over Rs 600 crore—the latter, in fact, did business of Rs 333.62 crore ($48.28 million) in China alone! It’s the third biggest Bollywood flick in dragon land after Aamir Khan’s Dangal (2016) and Secret Superstar (2017). So the new genre isn’t just a passing fancy of a new, globalised Indian. It has universal carry.

Ayushmann plans his films and scripts meticulously: after Article 15, he has four new movies, all different from one another, lined up for release between September this year and April 2020. In the rom-com Dream Girl, he will be seen in a sari. In Bala, he plays a young man worried about his receding hairline while he enacts a gay character in Shubh Mangal Zyada Saavdhan. In Gulabo Sitabo, he will share screen space for the first time with Amitabh Bachchan, the man who once personified superstardom but is now solidly part of the new scene. Vicky also has interesting projects, including Karan Johar’s Takht, and eagerly-awaited biopics of General Manekshaw and the revolutionary Sardar Udham Singh in the pipeline. Says Shoojit Sircar, currently working with Ayushmann and Vicky in Gulabo Sitabo and Sardar Udham Singh respectively: “As a director, the first thing you want to know is whether your actor is interested in the way you want to narrate the story.”

Sircar, who had given a break to Ayushmann in Vicky Donor, says he had signed him because he wanted a fresh face, not an A- or B-list actor. “I’m much more comfortable with youngsters who’re ready to take up any challenge rather than stars who come with heavy baggage,” he adds. Also, it’s a happy confluence of factors. Actors like Ayushmann and Vicky are experimenting with subjects at a time when audiences too are ready for it, says Sircar, who is about to begin shooting Gulabo Sitabo in Lucknow.

An actor of proven abilities who impressed everybody with Love, Sex Aur Dhokha, Shahid, Aligarh, Bareilly Ki Barfi, and Newton, the 34-year-old had a whale of a time at the box office with Stree, a horror-comedy directed by Amar Kaushik. The gifted actor now returns with Judgemental Hai Kya, his first film with Kangana Ranaut since Queen.

In the same mould as an unlikely actor-star—in fact, even more pared down in the looks department but very real with his screen presence—is Rajkummar Rao. He completes the triumvirate that holds down the logic of new Bollywood: witness only the phenomenal success of his low-budget horror-comedy Stree last year. He pulled in riveting performances in Shahid (2015), Aligarh and Newton (both 2017) and walked away with awards for Bareilly Ki Barfi, where he co-starred with Ayushmann. Rao is now awaiting his next big release, Judgemental Hai Kya, where he returns to pair opposite Kangana Ranaut—last seen together in the highly acclaimed Queen (2014).

Directors, actors…and audiences. It’s a table for three. The old kitsch doesn’t wash anymore, with or without the presence of superstars (see Taare Zameen Par). Filmmaker Anand L. Rai of Tanu Weds Manu fame has worked with all three —Ayushmann, Vicky, Rao—and puts things in perspective. “Every decade you get to see actor-stars with whom you fall in love for their talent or screen presence,” Rai tells Outlook. In the ’90s and noughties, Manoj Bajpayee, Irrfan Khan and Nawazuddin Siddiqui brought the ‘actor’s actor’ and a new edginess and intensity to a Bollywood that was beginning to change. The critical difference now, he says, is a certain sync between all three—auteur, actor and audience. “We are all evolving holding our hands together. There’s a certain growth of sensibility on all sides, including the audiences.” Vicky concurs: “If a film has to draw people to the theatres, it has to be better than what they already have access to on their cellphones. They’re smart enough to differentiate between good and bad.”

Manoj Bajpayee (left), Nawazuddin Siddiqui (centre) and Irrfan Khan charted a new course for Bollywood in the ’90s and noughties..

This is what impels filmmakers and actors alike to steer clear of the old, predictable and stale tropes. With platforms like Netflix and Amazon Prime, Indian audiences have begun to savour the best of world cinema; their aesthetic horizons have widened. Besides, large-scale migration of youth from smaller towns to metropolises has also changed the composition of multiplex audiences. A kind of realism is seeping in because people are responding to stories and characters drawn from the grassroots, who they can easily relate to. This is where, say, a Rao or a Kaushal clicks…real, riveting, one of us.

All of this has prompted even mainstream stars to go hunting for content. Even a big star like Ranbir Kapoor is taking calculated risks with unconventional movies like Barfi (2012), Tamasha (2015) or Jagga Jasoos (2017)—not getting deterred by lack of box-office success. Even Varun Dhawan, often called the Salman Khan and Govinda of the current generation, has been stealing time from hectic commercial schedules to do movies like Badlapur (2015) and October (2018). Sircar, who directed October, says it was very brave of him to have done a movie like that, which had nothing but clean and straight storytelling. “It turned out to be one of his best performances,” he says. “October was a challenge for him but he rose to the occasion to do a brilliant job.”

Film critic Deepak Dua agrees, saying Ranbir and Varun are destined for long innings because of their malleability. “They have the variety and are not averse to taking risks,” he says. “This is what makes them the proverbial ‘lambi race ka ghoda’ among the stars today.” As for Ayushmann, Vicky and Rao, he says they have benefited immensely because they have come at the right time. “Their movies are running simply because of good content, they don’t have the charisma or fan following to draw audiences on their own. But they are certainly smart enough to pick the right roles that suit them,” he says. “At the end of the day, it’s ultimately the market forces that control stars and the industry. I think in this era of transition, only Salman Khan has real star power.”

Regardless, every contemporary hero worth his greasepaint will give his right arm for a meaty role. Popular stars like Ranveer Singh, Sushant Singh Rajput, Arjun Kapoor, Sidharth Malhotra…they are all trying to go out of the box. The good, old Bollywood hero hasn’t exactly disappeared, of course. Witness Tiger Shroff, the new, improved edition of a marble statue that dances and fights. No filmography to back him, nor any allegation of acting that has stuck, but Baaghi 2 grossed over Rs 25 crore on its first day. Someone will always fill that space. But maybe he’s the exception that proves the rule: the majority of young actors now prefer to play Everyman rather than Superman.