In Bhooter Bhobishyat (2012), Anik Dutta’s debut film, a bunch of ghosts as diverse as a 19th century courtesan and a Kargil War veteran get up to all kinds of mischief to keep property/land sharks and politicians from laying their hands on their last refuge—an old, dilapidated house. It delighted audiences, especially the wordplay and puns, often in witty, rhyming doggerel that made up much of the screenplay, its droll darts hitting socio-political targets with ease, raising rolls of mirth. In February 2019, Dutta returned to the existential woes of a different group of spectral beings (hounded out of their last few habitats by multistoreyed buildings and malls, they now resolve to seek refuge in the digital world) in Bhobishyater Bhoot, an inversion of the title of his first movie.

Innocuously funny as the premise is, in this movie Dutta’s satire gets a sharper focus, and deals barbs generously across the political spectrum. Its sharpest bites, however, are reserved for the ‘Chhinnomool Party’. Quite predictably, this brilliantly comic takedown of the sinister bungling of a strongman-ruled outfit drew blood. A day after its release, Bhobishyater Bhoot was pulled out of theatres on February 16. As murmurs of a Trinamool Congress-imposed quietus gained ground, single-screen owners said a “technical issue” forced their hand, while multiplexes said it was an order from “authorities”.

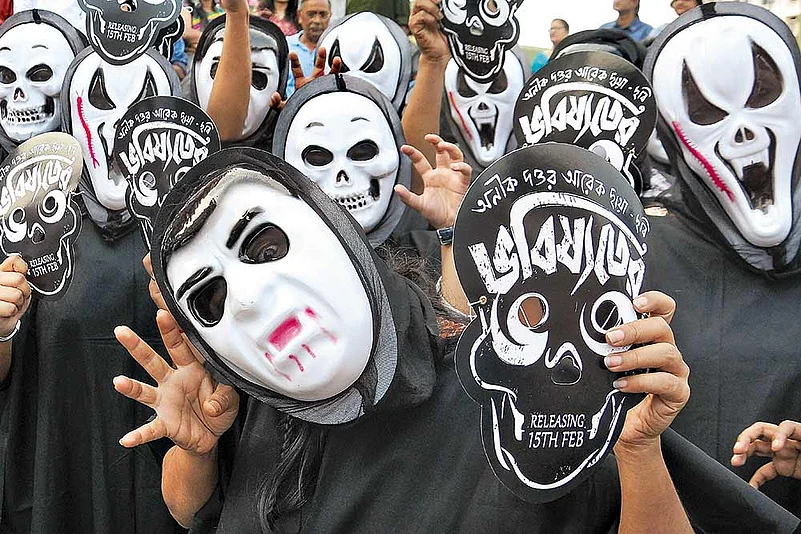

On March 10, actors, filmmakers and students took out a rally led by veteran actor Soumitra Chatterjee, filmmaker Buddhadeb Dasgupta, actor Jayant Kripalani, actor-director Aparna Sen and Dutta himself. Artistes and technicians from Tollywood film studios, young film enthusiasts and students wore skeleton and ghost masks depicting characters from the movie, with slogans demanding “an explanation” for the withdrawal of the film, alleging “silence by the administration and the ruling establishment”.

“My film was released on February 15; on February 16, without intimating our producer, they started taking off shows from theatres,” Dutta tells Outlook, ruing the loss of revenue.

That something was amiss was indicated by the Kolkata Police’s request for a special screening of the film before its release, a request that was turned down by the producers as the film was cleared by the censor board without cuts.

Ever since she gained power in 2011, Mamata Banerjee has assiduously cultivated film and cultural personalities in Bengal, putting together a sizable team who attend party functions and meetings—usually to show themselves to the public. Then there are the five actor-MPs of the Trinamool in the current Lok Sabha. Analysts say that a wily Mamata wooed filmstars to boost the image of the party, doling out patronage and state awards. That’s as far as carrots go; the treatment of Bhobishyater Bhoot embodies the stick-end of the deal.

The silent dropping of Dutta’s film, however, was a tipping point of sorts, with a section of Bengal’s intellectuals questioning Mamata’s “autocratic style and vengeance against criticism”.

Pointing to “a very evil nexus within the Bengali film industry”, Dutta says, “A section of Tollywood, is linked with the government, which has spread its tentacle within the industry but no one talks about it. But I have been talking about it for a while.” He alleges the existence of a couple of government-controlled industry federations. “It’s a kind of quid pro quo. These people decide which film will be released and exactly for how long.”

Terming the rhetoric about Bengal being at the vanguard of Indian democracy as mere cant, Dutta recounts that he faced hurdles from the first day of production. “Somehow we finished the film, because my crew and cast stood behind me.”

Bhobishyoter Bhoot is about people rejected during their lifetime, who were almost like living ghosts while alive; when they die, they form a collective that gathers in a place that was a refugee camp. “The film talks about marginalised people who have become irrelevant…it has a political slant.” In the film, “future ghosts” debate if embracing technology and the cyber world would help them stay relevant.

“In doing this, I have tried at least to show what is going around at the grassroots level, or at political or socio-political levels,” says the filmmaker. He was paid the wages of truth-telling—a stealthy cosh on his film.

By Probir Pramanik in Calcutta