In April last year, two clowns stood in an empty auditorium with their eyebrows arched skywards, a red nose stuck onto their faces as they began their performance. I saw them on the screen. We were in different cities. Isolated, scared and full of nostalgia for a past where we sat watching the clowns do their acts inside a tent. That was long ago.

When the clown and the rest of the crew performed in front of the camera on the night of April 16, 2020, in Airoli in Mumbai, I wanted to clap. I did. In my room in Delhi. I was reporting the story about the circus in the pandemic. But later that night, I remembered the circus I went to as a child where I first noticed the women in their glittering costumes crisscross the space suspended from ropes. I remember I wanted to be them. They had looked so unreal, so beautiful, so powerful. So outwardly.

The Rambo circus crew of about 100 people were waiting for things to get better, they had said. Biju, the clown, told me they were used to the audience clapping, egging them on. The empty tent was a strange place. It was their performance for the World Circus Day on April 18. The performance that was streamed online was their gift to people. The clowns, the acrobats, the rope walkers wanted to take us back to a happy place in the past.

Biju, 50, was wearing his polka dot overalls. He had painted his face with white powder and had reddened the cheeks with vermilion and lipstick, a trick he learnt early on.

I remember he started with an appeal to wash hands, wear masks, stay home, etc.

I remember a young girl who entered the space with chandeliers that held burning candles in her hands. She held a candle between her lips. She danced a slow dance and twisted her body. The candles stayed put. The chandelier didn’t crash. She bowed as usual. Nobody clapped. She hadn’t forgotten the manners.

Biju told me later that he had seen a lot of ups and downs in life but he had never imagined a time when he would come close to witnessing the curtain fall on the circus forever. But forever is a confusing thing. It is such a final thing, he had said. I told him perhaps there would be a way out of this crisis. Nostalgia is time travel. We all have that thing for it. Circus was a destination on the nostalgia map.

The Rambo circus ran out of food and money soon after the lockdown was announced. The owner of Rambo Circus Sujit Dilip had to appeal to public for help.

Biju told me all this over the phone from his small tent in what he calls a “moving village”, a temporary place with a lockdown in place and a pandemic raging outside.

Many circuses shut shop. In a town called Arammbagh in West Bengal, Olympic Circus gave up. All 75 members of the crew had left. When I had called them, nobody picked up. The ring tone, I remember, was a song from a film from many years ago called Mera Naam Joker where Raj Kapoor in his overalls and wearing a heart-shaped mouth held a glass heart sang a song about the eternal place of damnation and redemption called circus where a clown comes on stage to make others laugh. I thought it was a sad song. My father played it often. That’s how I saw the circus. A place of courage. A place of hope. A place of truth. A place of magic.

Chandranath Banerjee, 61, had inherited the Olympic Circus from his father Subodh Chandra Banerjee in 1975. On March 19, 2020, he announced that the circus would be closing down for the time being. He told me they had cried.

With isolation as the new norm, we had to stop.”

The Olympic Circus was founded in 1942 by his father, who used to perform in a circus in those days as a gymnast. They even went to Japan once, Banerjee told me.

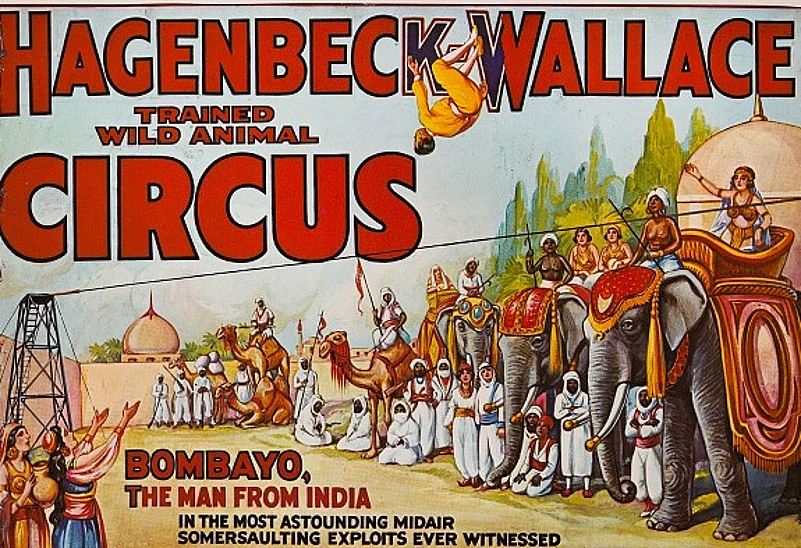

It is the nostalgia of a time when circus was an entertainment, a window to the world, a magical place, a place of possibilities where girls jumped through rings of fire and men spewed fire and animals danced and clowns told stories. The advent of television took away a lot. They were travellers. I was fascinated with their lives. They wandered, pitched their tents, performed and left.

Juggling, acrobatics, gymnastics, aerial acts like the trapezium and aerial silk, fire-eating, and sword-swallowing. And more. Perfect for nostalgia.

It was only in 1880 that circus as devised in the west came into being in India. The Great Indian Circus was the first one to start performing in Maharashtra. In 1901, the Kerala government started a Circus Academy in Thalassery. And in 2010, a new academy came up in Thalassery with just 10 trainees and eventually shut down.

All those conversations were transcribed and filed. I return to them sometimes. I liked the circus. Dilip’s father PT Dilip worked in Arena Circus and then he bought three circuses – The Great Oriental Circus, Victoria Circus, Arena Circus - and merged them together 30 years ago.

They named it Rambo in 1991 after they saw the dictionary meaning. It meant strength, Dilip told me.

Dilip, who had been a science student, quit his studies and took over the reins of the circus from his father and it made him sad to see the circus struggle.

As a child, he spent his vacations at the circus. He would wake up early and feed the lions and tigers with the ringmaster. Back then, they had 28 lions and two chimpanzees and two tigers and they would cross breed them inside the circus.

I remember a post on Facebook by Sujit Chowdhury. It was in the early days of the lockdown. He wrote about his memories of attending circuses in a small town.

“One experience I recall vividly is how after watching the famous Gemini Circus at Delhri-on -Sone and some Sorcar Magic shows ( all magicians had the Sorcar in their name ) in my hometown. I got so inspired at the age of 7 or 8 that I started copying the tricks in my own way . With some ropes and bedsheets , a small tent was erected under the mulberry tree of my garden. Out of two caged parrots, one was taught in vain to do some funny acts and in that futile process the poor parrot died… My cousin sister tried to walk on a rope and do some gymnastics like passing through metal rings that we had seen in the circus . We arranged a big wooden box and my sister used to go inside, then cover it and she used to get out from backside and hide in the backside thick bushes . That was the famous vanishing act recreated by us drawing amazement and applause from my audience,” he wrote in Life in the Time of Corona. “Those facts and fantasies shaped our worldview in a small town of Bihar. Our reality and existence is divided between remembrance and forgetfulness.”

Many years ago, I had been to a circus in Arrah in Bihar. My aunt lived there and so did my maternal grandfather. Of the many childhood memories, one is about a circus. I remember that the circus ground looked like a fantasy world with all the lights and once inside, I first heard a lion roar, a trapeze artist perform and the rings of fire, capes and tights, and tiara’d young women in sequined outfits astride elephants, sliding down.

I must have been six or seven then.

I wonder about Biju, the clown, and the rest. I know they survived. They had started doing online shows.

But I want to sit inside a circus tent and watch an old circus clown tell me about a pig who talked like a parrot. Why not.