Arattle of kettle drums and thunder rends the air as Bali, Kishkindha’s monkey king, strode across a stage, bringing into Chennai’s Museum Theatre a sense of the devastation taking place in neighbouring Kerala. For 70 minutes during the Hindu Theatre Festival 2018, the Adishakti group, started by the late Veenapani Chawla near Auroville, enacted the story of Bali. In Valmiki’s Ramayana, it was coincidentally during the rainy season that Ram and Lakshman, seeking allies in their mission to rescue Sita, had reached Kishkindha—better known today for the scattered ruins of Hampi, with its rock-strewn landscape in the Karnataka stretch of the Western Ghats. The two exiled princes from mythical Ayodhya found themselves drawn into the uneasy alliance between the two brothers Bali and Sugreeva.

Setting off to fight a demon in a hill cave, Bali had told Sugreeva to pay heed to his death only when he saw a river of blood flowing down the mountain side. In a striking visual moment of the Adishakti production, a beam of red light was streamed across the stage, while red balls were tossed, or rolled silently, from one darkened end of the stage to another. Could Bali be dead? Sugreeva greedily seized the moment. He took over Bali’s kingdom and his wife Tara, who had risen from gem-strewn waters during the churning of the mythical Ocean of Milk.

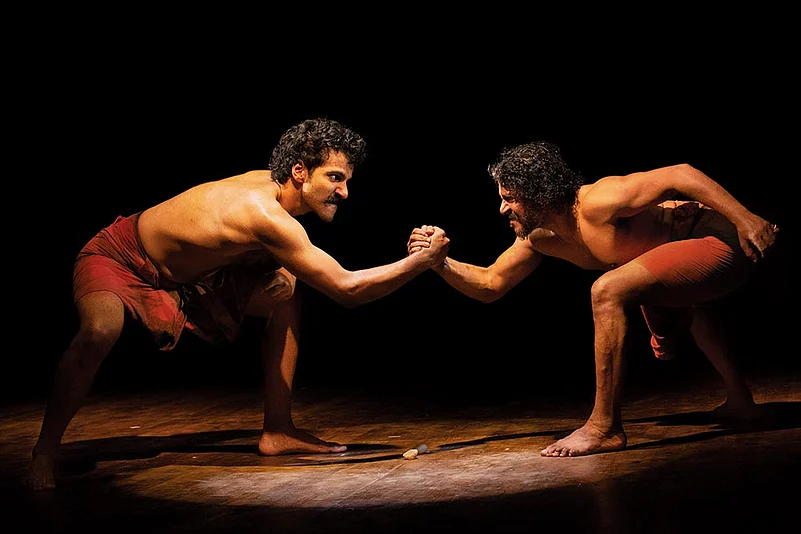

In earlier sequences, a bare-bodied Bali, his muscles rippling, indulged in some lungi machismo—two angry young men girding their lungis and preparing to fight, or unfurling them to indicate they would surrender for the moment, is still a common sight in the streets of Kerala. Bali and Sugreeva too raised and lowered their lungis like flags before a battle. The earth shook when they lifted their right knees to waist height and thumped the ground like Sumo wrestlers. As Ramayana commentator C.G.R. Kurup depicts the scene, “fighting with mountain peaks, trees, fists and arms, they looked like a pair of contending clouds in the sky”. He could well be a TV anchor reporting the news of the devastating flood.

Like Valmiki, the Adishakti production emphasises that Kishkindha’s denizens were monkeys. There is a clear Aryan/non-Aryan bias in the Ramayana. Were they monkeys? Or adivasis? As Ram could not tell Bali from Sugreeva during their fight—they were identical twins, some authorities claim—Lakshman had to place a garland around Sugreeva’s neck, while Bali wore the gold chain given by Indra, their father.

As images of betrayal and wrong choices made by the protagonists in the epic were brought to life on the stage, what was evident is the rage between Bali and Sugreeva. Ram, by contrast, was calm, if not stoic. When Sugreeva showed him how Bali made a hole through a Sal tree, Ram was able to effortlessly shoot his arrow through seven Sal trees and smash a rock into two for good measure.

Bali’s son Angada, an heir without a kingdom or even a future, had asked Ram, “Have I alone no role in avenging my father’s death?” There was also a small fragment in which Bali sat on the floor with a bowl of rice powder in his hand, for initiating Angada into learning to write. Known as Vidyarambham, it’s an important moment in a child’s life in Kerala—tracing vowels in the white powder with the child’s index finger guided by the preceptor’s. When Angada kept smudging the vowels, did it indicate he won’t have much of a future? Maybe he really was the son of a monkey. This was perhaps what made Ram treat them not as equals, but as the ‘other’—a dark-skinned race, with indistinguishable features. So, was it somehow alright for Ram to use less than heroic means to ensure Bali’s defeat?

The Adishakti production uses traditional methods from folk theatre to create moments of comic relief. While the two brothers battled over who should rule Kishkindha, two young women, one huge and loud with an overhanging belly, the other small and deft, squabbled over small trinkets and lines of demarcation—the way states today fight over their share of river water and, when the river is in spate, rent the air with cries of despair.

The main actor, Vinay, has always had a very strong Kerala accent. In earlier productions, his ability to go back and forth speaking in Malayalam and English was part of the comic effect. Towards the end of Bali, there was a laconic exchange between Ram and the resurrected Ravan. “Would you have returned Sita if Bali had come to you?” asked Ram. Vinay, as Ravan, replied: “And now you will never know.” The audience rose as one to clap.

Nimmy Raphael, who directed Bali, follows the method of Veenapani, whose wooded retreat at the fringes between Auroville and Pondicherry is called the Adishakti Laboratory for Theatre Art Research. Based on traditional forms such as Koodiyattam, Kallaripayatu and Chau, Veenapani’s method gives slow body movements more importance than words. A number of dramatic images, mimetic actions and sequences of sound are created for a pattern to emerge. The actors learn to create moments on the stage through a continual exchange of what can only be described as ‘frequencies’—images formed through sound.

In Bali, the battle was rendered with an image of white ropes winding and re-winding across the stage floor like the twisting of the varied destinies of the individuals trapped in its coils. There was a moment of redemption towards the end when the Tree of Life and Death appeared once more and Bali walked towards it, arms raised, in an embrace of his destiny—neither monkey, nor man, but pure soul.

Could Ram admit to having killed Bali unfairly? Or was he only looking for the quickest way to achieve his goals? This was eloquently handled by the Adishakti team. As Bali reminded us, in his last words on Ram, “even the moon has spots, the tips of a lotus bloom are pale, so why not a hero who also has flaws?”

By Geeta Doctor in Chennai