Parassala B. Ponnammal was only 16 when she got a grade as a singer with All India Radio. That was in 1940, when India had just a handful of broadcast stations and the one nearest to her house was at Trichy by the Cauvery, over 400 km from her village in the kingdom of Travancore. Teenaged Ponnammal went on to perform at weddings as a Carnatic vocalist, before her career took a curious turn.

By 1942, soon as she topped a three-year course from Swathi Thirunal Music Academy in Thiruvananthapuram, Ponnammal got her first job: as a teacher in the city. From then, the artiste pocketed several firsts alongside a rising profile, but all under the shadow of a strange irony spanning seven decades. Tamil Nadu, and its capital Chennai, where Carnatic flourished after Independence, totally ignored Ponnammal after the Trichy milestone.

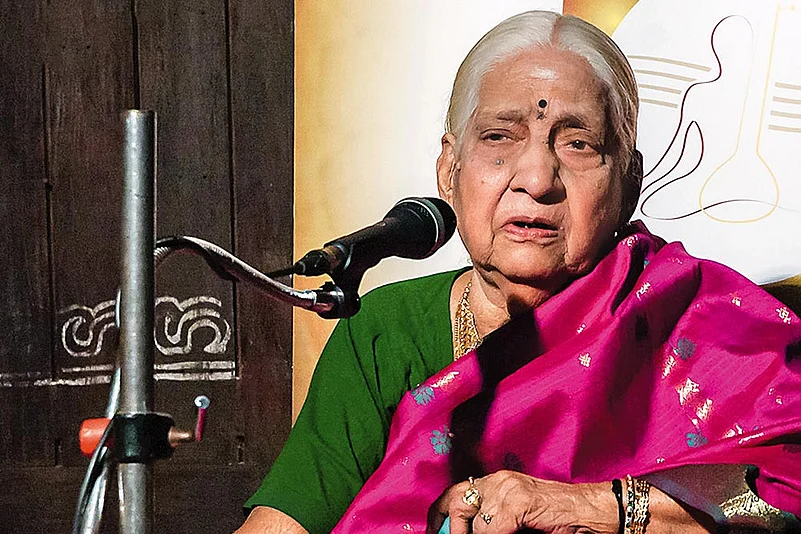

It was only in 2009, when the musician was 85, that the prestigious Madras Music Academy invited her for a concert. This year, the 92-year-old was conferred with a Padma Shri. “People say this should have come to me long ago; maybe yes, but I’m fine,” says Ponnammal, graciously. “For the past one decade, I have been unusually busy. Not just in south India, but even abroad (at the Cleveland festival in the US).”

A frontline disciple of 20th c icons Harikesanellur Muthiah Bhagavatar and Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer, even in her native Kerala she wasn’t much celebrated either for long. Often slotted as a theorist-teacher, she was seldom heard in the concert circuit. Then, in 2006, she got a big ‘break’ when the annual Navaratri Mandapam festival at Thiruvananthapuram’s Padmanabhaswamy temple invited her to perform—the first-ever female artiste to be called to that ceremonial occasion, which was into its 187th edition then. The octogenarian, performing on day one, expanded upon the Sankarabharanam composition of Swathi Thirunal (1813-46).

The historic performance was the result of a 22-year struggle by musician Rama Varma of the erstwhile royal family—traditional patrons of the festival. “As a teenager, I kept asking elders why the mandapam had always been an all-male affair. None had an answer,” trails off Varma, a disciple of late M. Balamuralikrishna. “When I won in my mission, I ensured that the debut should be marked by an exponent who breathes music.”

Baby Sreeram, another female vocalist to perform at Navaratri Mandapam, attributes Ponnammal’s “effortless, errorless and matured” music to her lifelong discipline. “I’m told she never gave private tuitions; instead spent quiet hours after her day’s teaching in institutions,” notes Baby. Ponnammal joined the Academy as a teacher in 1952 and helmed RLV Music College near Kochi for a decade from 1970.

Madurai-based vocalist K.N Renganatha Sharma, whose father Cherthala Narayana Iyer was a contemporary of Ponnammal at the Academy, values the “restraint” in her music. “She doesn't go for cerebral exercises with rhythms, or that over-flourish in swara progressions.” Author-archivist Krishna Moorthy rues the lack of too many recordings of Ponnammal in her prime. “That would have given better direction to new-gen musicians keen to break tradition,” adds the scholar who has written a biography of vocalist Neyyattinkara Vasudevan.

Sreevalsan J. Menon, a disciple of Vasudevan who learned a few kritis from Ponnammal, cites her dignified approach. “Replicating some of her trademark gamakas is next to impossible.” Chennai-based veena player-banker S. Sivaramakrishnan recalls how the city’s music circles are entranced by Ponnammal’s lesser-known compositions. “Some hail her as a ‘golden girl’. They have stumbled upon a DKP from Kerala,” adds the aesthete, referring to D.K. Pattammal, who also hewed close to the lower (mandra) octave.

Ponnammal’s music mirrors the purity of her mind, says researcher-singer Ajith Namboothiri, a TV anchor for classical music programmes. Adds Kozhikode-based organiser Nochur Narayanan: “She never went after anything. It’s all a long backlog of deserving honour coming now.”