It’s Medalomania!

- The navy permitted moustaches without beards only after 1971

- The bar curl is reversed

- The Kargil Star, awarded in 1999, when the land war took place

- Op Parakram, the Indo-Pak desert standoff after the 2001 Parl attack

- Silver Jubilee Medal 1972

- The Kargil Medal—another anachronistic blooper

- The name tag was introduced by the Indian navy only in the 1970s

***

When the trailer of Mohenjo Daro came out, it came under merciless trolling on social media—the main point of criticism being the costumes. All of us have learnt a bit about the Indus Valley Civilisation in school, and absolutely none of the pictures of statuary found at the excavation site showed people clad in designer clothes of the kind characters in the film wear. There was no intricate stitching in 2016 BC, when the film is set. The clothes were likely roughly woven fabric—as the famous bearded man statue shows, simply draped printed cotton was in vogue.

In the film, Hrithik Roshan wears pleated dhotis and neatly stitched sleeveless ‘bandis’; other men wear what in today’s parlance would be described as ethnic chic. Elaborate headgear and gladiator sandals are spotted too. The leading lady, Pooja Hegde, is made to wear slinky gowns silt to the thigh and a comical headdress made of feathers, beads and buttons—a faux Cleopatra. Yes, hundred per cent accuracy may not be possible in a recreation, but such utter disdain for history is seen only in mainstream Hindi cinema.

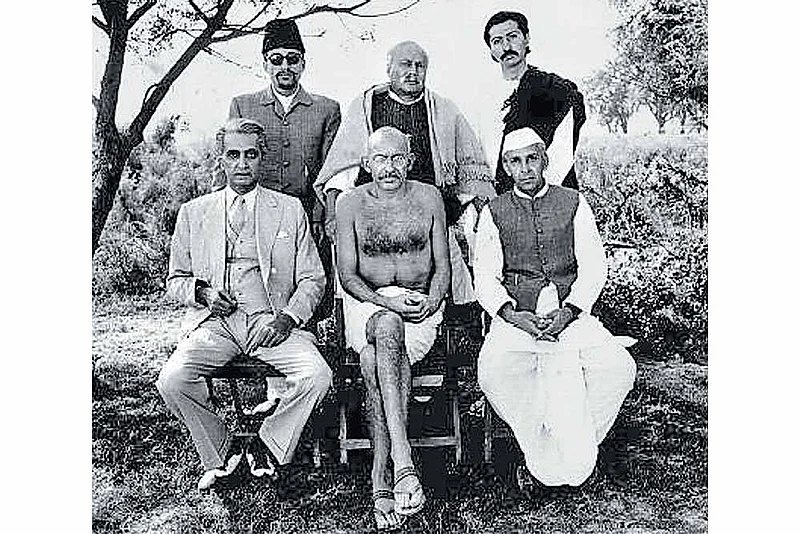

The dramatis personae in Attenborough’s Gandhi

Subsequently, another photo went viral, showing all the bloopers in Akshay Kumar’s naval outfit in period drama Rustom—mainly the medals lining his chest that do not belong to 1959, but to a later era.

One can almost imagine the costume designer telling an assistant to go get some medals, then pinning the shiniest ones on Commander Rustom Pavri’s uniform, with a more-the-merrier attitude. The designer, Ameira Punvani, has been quoted as saying that taking cinematic liberties is okay, and if the film is entertaining, the audience would not care. Which is sadly true—the audience’s indifference allows designers/filmmakers to ignore basic research.

Strangely enough, the bigger the film the more the disdain for authenticity; if there’s a star, the filmmaker hopes the drooling audience won’t notice; or the director couldn’t either, which is more likely. He/she has enough to worry about, the correct uniform or fabric is not a priority.

Even Sanjay Leela Bhansali, known for his grand epics, was pulled up by experts for making Priyanka Chopra and Deepika Padukone wear suede cholis in the Pinga song in Baji Rao Mastani, when this fabric did not exist in the 18th century. The draping of the nine-yard sari also came in for rebuke, because a Brahmin royal like Kashibai would not wear it tight around the hips and thighs, like a lavni dancer.

In period films, say Razia Sultan or Umrao Jaan, it’s common to see actors wearing fabric like chiffon (the fall is better) and contemporary make-up like lipstick, eyeliner and nail polish. Even the famed ‘perfectionist’, Aamir Khan, wore, in Lagaan, boots that a poor farmer could not have afforded, even if the style existed in colonial India.

If Hollywood makes a period film, there is a research team at work to assist the costume designer; even then, hawk-eyed viewers notice, say, anachronistic jewellery, or a watch—something that slipped the eye of the continuity professionals.

When an Indian designer works on a foreign film, like Bhanu Athaiya did in Gandhi, he/she has to conform to higher standards. Athaiya won an Oscar, because her work was meticulous. Richard Attenborough would not have settled for less.

Hrithik Roshan and Pooja Hegde in Mohenjo Daro

Filmmakers like Shyam Benegal spend time on research and hunt down the right kind of clothes/accessories, even with limited budgets. Benegal’s TV series Bharat Ek Khoj, or period films like Bhumika, Junoon, Zubeida and Netaji, have an attention to detail missing in commercial films.

However, even if a film is careful about period details, like Byomkesh Bakshi, for instance, there will still be a careful viewer who will point out that a particular kind of shoe was not manufactured in the mid-20th century.

It’s not as if visual reference material is not available to filmmakers and designers. When a filmmaker wants to be accurate, and has the resources for research, the result is a film like Mughal-e-Azam. Legend has it that K. Asif would not agree to use fake zari or artificial jewellery, even when the texture and colour would not show up in a black-and-white film.

The film did not have a designer, but a costume department. According to film trivia, tailors were brought from Delhi to stitch the costumes, specialists from Surat-Khambayat were assigned the task of doing embroidery, Hyderabad goldsmiths made the jewellery, Kolhapuri craftsmen designed the crowns, Rajasthan ironsmiths crafted the weapons, the elaborate footwear was made-to-order in Agra. Even the chains used to bind Anarkali were genuine, heavy iron that left blisters and bruises on Madhubala’s skin, but the director would not make any compromise, even it meant the film took over a decade to make.

A filmmaker like Sohrab Modi, who made a number of historicals, did not have highly paid fashion designers on his crew, but took care to see that the look of the period was not distorted.

Today, with star designer and stylists on call, and the internet rendering research relatively painless, this contempt for detail is indefensible, and the excuse that the audience will not notice flimsy. Well, somebody does, and it is all over social media. Inaccuracy might not affect box-office collections, but it does make a difference somewhere. Which is why Mughal-e-Azam is a masterpiece and Mohenjo Daro is not.