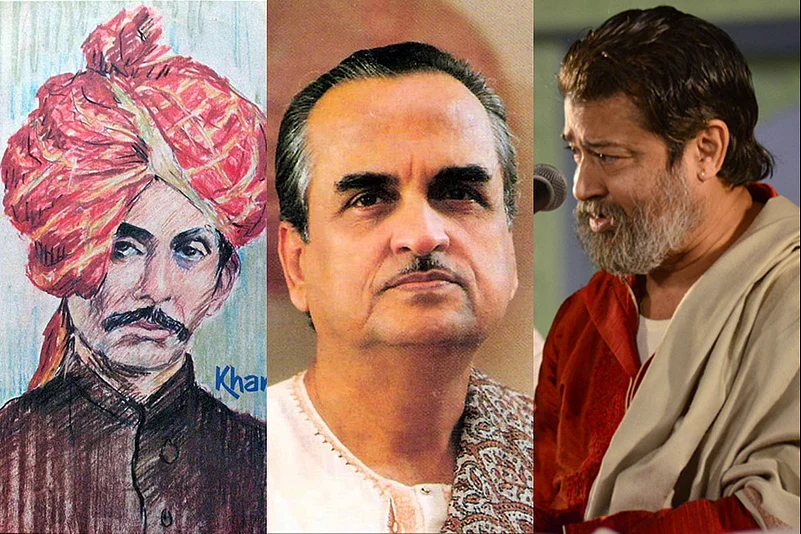

A decade after the turn of the 20th century, a famed vocalist from the Hindi heartland went down south of his country on a professional assignment that went on to script a major chapter in the history of Indian music. Hindustani exponent Abdul Karim Khan was in Mysore during the sandalwood city’s famed Dussehra festival celebrations, amid which he gave concerts—only to be soon called by the royal Wodeyars who were patrons of the arts.

From 1915, Khan saheb began to receive regular invitations from Maharaja Nalwandi Krishnaraja. If that gave Hindustani music a near-regular venue in Mysore, it also led to a symbiotic relation between the two classical streams. For, the ustad, who was a native of a historical spot near Muzaffarnagar (in today’s western Uttar Pradesh) and from a family of musicians, deeply fell in love with Carnatic. That was owing to his close interactions with the south Indian classical musicians at the Wodeyar court, where he was also a noted guest.

The life in Kannada land fetched Khan saheb an unlikely friend: a dog (nurturing of which is forbidden under Islam). What’s more, he named the pet (bought from Bagalkot near Belgaum) Tipu, ostensibly after the 18th-century sultan of Mysore. The story didn’t end there: the dog was a big draw at the concerts of the maestro, who found that the animal was “able to produce reproduce the musical notes that were recited in his presence”, according to an authentic book. “Some archivists like Michael Kinnear of Australia possess handbills of his (ustad’s) variety shows, listing the dog’s ‘performance’ as one of the items,” notes The Oxford Encyclopaedia of the Music of India. Khan saheb’s disciple-biographer, Balakrishnabua Kapileshwari, claims that the dog’s “talent” was demonstrated first at a “special show in Satara, Maharashtra”, followed by similar events in Pune and Bombay.

Whatever, it wasn’t just in Kannada land that Khan saheb spent his prime-time southern days (after stints in Baroda and Bombay). Hyderabad was another of his stops. Adept also in playing the rudraveena, sitar and sarangi, he made his artistic forays into Madras, where the ustad even set up a music school in 1923 (though it didn’t run for long). By the late 1920s, almost a decade before the master’s death (at age 65), he began singing in several Chennai venues, including the nascent Madras Music Academy that went on to become iconic for Carnatic. Records refer the ustad as the first Hindustani musician to learn south Indian classical.

Not surprising, thus, that there was sufficient dose of Carnatic aesthetics in the style of Abdul Karim Khan. The gharana (school) he founded came to be known after his native Kirana, and has its subsequent torch-bearers carrying the legacy—and it can’t be a coincidence that quite a few of them are from (northern) Karnataka.

So, how does it sound when the ustad sang Carnatic? A recorded piece is a composition by Tyagaraja (1767-1847), who is a vital figure in south Indian classical. Heard here is Rama nee samaanamevaru (Who is equal to you, Ram!) tuned to Kharaharapriya, a raga that has a parallel up north: Kafi.

The rendition does gain a novel flavour, primarily because of the ustad’s moorings in the Hindustani style or rendition. More often, the notes sound like surfing than ploughing, which is a key characteristic of Carnatic that revels in microtone-rich kambita gamaka. The contours enter unconventional spaces, thoroughly amusing and refreshing. The sargam passages, where solfas are delivered in sequence, tend to form patterns, which is an obvious south Indian trait.

Abdul Karim Khan (1872-1937) hasn’t been the only Hindustani vocalist who has learned Carnatic (though not quite mastered it). The renowned Dinkar Kaikini (1927-2010), who was first taught under Patiala gharana’s K. Nagesh Rao before he made S.N. Ratanjankar of Lucknow his guru, has had a penchant for the south Indian classical singing.

Here is a Carnatic-style piece by Kaikini himself, composed in raga Kalyani that has its equivalent of sorts in Yaman upcountry. The vocalist ensures that the introductory brief alaap has the forcefulness and brokenness typical of Carnatic and that the composition is speedy enough. The tabla, by fellow Mumbaikar Yogesh Samsi (and a disciple of legendary percussionist Alla Rakha), suitably sounds more like the southern drum mridangam.

The vocalist—his colophon being ‘Dinrang’ and all his compositions available in the book Rag Rang—has also gone for a spirited rally of notes that sounds like the swarapastharam in Carnatic.

If Kaikini’s Kalyani tends to bear a Yaman hangover more often than not, a different feature defines Mukul Shivputra’s raids into the field of Carnatic. At a Pune concert a couple of years ago, the top-ranking vocalist (now 61) goes for a leisurely collage of Carnatic tunes. The ragamalika has three melody-types, and they do sound eminently south Indian even as the oscillations the artiste employs are more like from the school of his titan father Kumar Gandharva (1924-92).

Mukul, known for his mood swings and nomadic life, met up M.D. Ramanathan in Madras and learned under the unorthodox Carnatic vocalist for a year in the 1980s. Here in the video, the “disturbingly gifted” genius (as once described by late musicologist Raghava R. Menon) does bring out certain core feel of Bhairavi (not to be confused with its Hindustani namesake), followed by Varali, which, again, is not a stylised tune up north. The third raga, Mayamalavagoula, though does have its Hindustani counterpart: Bhairav.