For eight months before the 1983 state elections in undivided Andhra Pradesh, a modified green Chevrolet van would travel non-stop, except for the occasional pit stops and food breaks, across the state. Atop the van was Nandamuri Taraka Rama Rao, popularly known as NTR. The beloved superstar had a fan base that comprised millions, all of whom waited with bated breath to catch a glimpse of their beloved anna (brother). But this time it was not only because he portrayed Krishna, Karna and Duryodhana in movies, but as the founder of a new political party—the Telugu Desam Party (TDP)—that led with the slogan of Telugu self-respect. The vehicle, which reportedly logged 75,000 km, heralded a new era in the politics of the state by overthrowing the Congress government—something that had never happened in the history of south Indian politics.

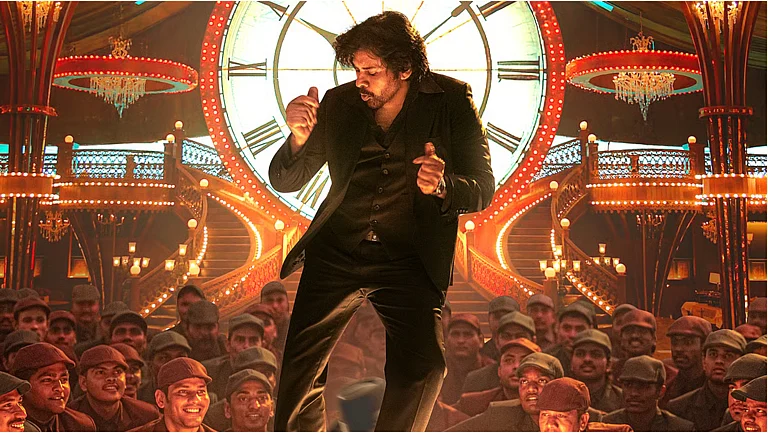

Four decades later, when Union Home Minister and BJP leader Amit Shah met Tollywood star, N T Rama Rao Jr, grandson of NTR, in Hyderabad—some called it a ‘courtesy meeting’—it didn’t catch many by surprise. Although the BJP had publicised the meeting claiming that it was arranged to appreciate the star’s performance in S S Rajamouli’s RRR, where he played the fictional role of Komaram Bheem—a revered tribal leader from Telangana—film historians and tribal activists alike observed that the meeting happened against the backdrop of attempts by the Hindu right to appropriate Adivasi leaders and the party’s strategy of using Tollywood actors as vote catchers.

Shortly after RRR’s teaser was released, a BJP MP and Adivasi leader, Soyam Bapu Rao, objected to Bheem being depicted wearing a taweez (amulet), a Muslim skullcap and a pathani kurta pyjama. He further claimed that Bheem was a “Hindu fighting against Islamic rule”—a claim strongly rejected by Adivasis in the region. While there was speculation that NTR Jr would join the BJP soon after the meeting, nothing of that sort has happened, yet.

Tamil Nadu: A State Led by Actors

Though Mumbai and Bollywood may come to one’s mind when asked about India’s film industry, it was in south India, particularly Tamil Nadu, where film stars have made the biggest impact in politics. In fact, it has been almost six decades since the state has seen a non-cinema-related chief minister being elected by the people—C N Annadurai, M Karunanidhi, M G Ramachandran, J Jayalalithaa and M K Stalin have all been connected with cinema in one way or the other.

“It is erroneous to believe that their success had anything to do with ideology. It is only necessary that the actor is able to collect a large number of local caste groups,” says M K Raghavendra, a film critic.

At the same time, the Dravidian movement for non-Brahmin upliftment—that took shape to address caste-based discrimination during the first half of the 20th century—found its perfect ally in cinema. So much so that The New York Times carried an article during the electoral campaign of 1967, describing film star involvement in the politics of Tamil Nadu as having “a touch of California”. It was in this year that the DMK, led by Annadurai, became the first regional party to form a government in a state.

The characters played by these stars earned them a large and loyal fan base—both in the film world, and subsequently, in politics. Jayalalithaa was often the powerful, flamboyant goddess (Aathi Parasakthi, 1971), but could still play the down-to-earth peasant (Adimai Penn, 1969). MGR too could play a working poor man (Thozhilali, 1964) or a rickshaw puller (Rickshwakaran, 1971), always combating everyday oppression. The two paired together—when MGR was in his 40s and Jaya in her early 20s—creating magic on screen, where Jayalalithaa wasn’t cast just as a shadow, but as someone who had her own personality.

As academic Robert L Hardgrave writes, their films—which included themes like untouchability, self-respect, abolition of the zamindari system, prohibition and religious hypocrisy—were vehicles for both social reform as well as party propaganda. In most movies, a character called “Anna” appeared as a wise and sympathetic counsellor. It wasn’t pure coincidence that Anna translated into brother in local languages and was also a popular name for Annadurai.

As they gained prominence as political leaders, people were thronging to see them at public meetings, Hardgrave writes. So people would vote for this common working man or woman—whether for Anna or Amma, as Jayalalithaa was popularly known.

But their electoral fame wasn’t only about their ideology or what they represented in movies. “It is erroneous to believe that their success had anything to do with ideology,” says M K Raghavendra, a film critic. It is only necessary that the actor is able to collect a large number of local caste groups, he says. Writing on similar lines, S V Srinivas, a professor at Azim Premji University, Bengaluru, in his book Megastar: Chiranjeevi and Telugu Cinema After N. T. Rama Rao, explains how fans form associations for their stars who belong to the same caste. “A large number of fans of superstars are young men, belonging to the lower and non-Brahmin castes. Dalit men also find a fair representation among the groups of certain stars… but there are simply not enough stars for each caste to have one of its own,” he writes. So when NTR, who belongs to the Kamma caste, became popular in his community, it was for the first time that someone other than the ‘Reddys’ was occupying a position of political power. Hence, the community threw its weight behind the actor.

While film critics and historians agree that a star’s popularity does offer an initial political advantage, they caution against assuming that popular stars will always be successful in politics. Srinivas cites the example of Tollywood actor Konidella Chiranjeevi’s disappointing electoral performance in Andhra Pradesh in 2008. The actor, known for his blockbuster performances in Indra (2002), Tagore (2003), and Shankar Dada M.B.B.S. (2004), floated his own party, the Praja Rajyam Party (PRP) in 2008 as an alternative to the Congress and the Telugu Desam Party (TDP) in the then undivided Andhra Pradesh. But the party proved to be a flop, unlike his movies, after winning only 18 seats in the 294-member assembly in the 2009 elections. He then merged his party with the Congress party and became a Union Minister, but eventually bid goodbye to politics after the national party became almost non-existent in Andhra Pradesh, post its bifurcation.

While film critics and historians agree that a star’s popularity does offer an initial political advantage, they caution against assuming that popular stars will always be successful in politics.

A similar script was awaiting Kamal Haasan in Tamil Nadu. He marked his foray into the political arena of the state after the demise of political stalwarts—Jayalalithaa in 2016 and M Karunanidhi in 2018—which left a vacuum in the state’s political landscape. “But he was a failed politician,” says Veejay Sai, an author and culture critic. He had no idea of the ground reality in the state and failed to make his political ideology clear, says Sai. His party, the Makkal Needhi Maiam (MNM) drew a blank in the urban local body polls in 2022, and prior to that, garnered only 2.6 per cent vote share in the 2021 assembly polls. Haasan himself lost from the Coimbatore (South) constituency, Sai recalls. “Politics is not as simple as cinema,” he quips.

As written in the book Onscreen/Offscreen (2022) by Constantine V Nakassis, Haasan did not embrace the hegemonic Dravidian political ideology; instead, he declared his party would take the “middle” way.

Rising Star Leaders

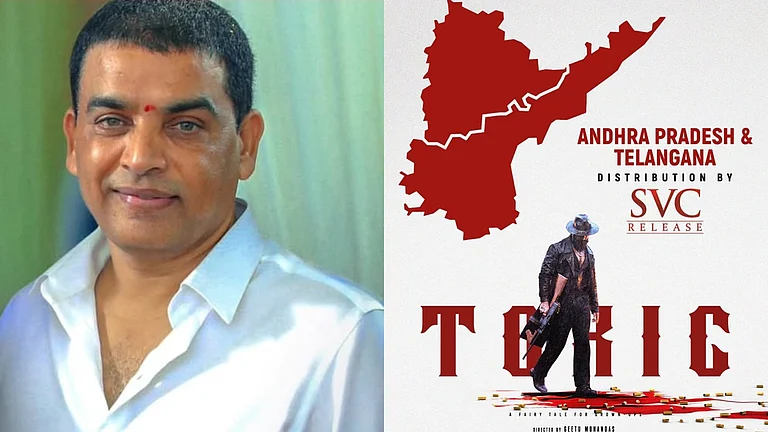

As the Lok Sabha elections are drawing near, more and more film stars are either joining politics or merging their existing political parties with bigger/national ones. In Andhra Pradesh, the one star to watch out for, Srinivas says, is Pawan Kalyan of the JanaSena Party. “Not because he will be chief minister in the near future,” he clarifies, but because he is part of an alliance that has a chance of coming to power at the state level.

The actor-turned-politician, who appeared in the 2013 blockbuster Atharintiki Daaredi founded the JanaSena Party in 2014, which, he says, represents politics without caste or religion. “I have no caste. No religion. I am an Indian,” his voice thundered at the launch of his party in Hyderabad. Although his party did not put up any candidates in the elections that year, Kalyan lent unconditional support to the TDP-BJP alliance, campaigning alongside the then TDP chief N Chandrababu Naidu and the then prime ministerial candidate Narendra Modi.

However, over the years, Kalyan has made several flip-flops in his ideology. He teamed up with the CPI and CPI (M) and endorsed the cause of Dalits by welcoming the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) into the alliance in 2019. Best known for his on-screen roles as the ‘angry’ and ‘defiant’ hero, Srinivas says that Kalyan’s rhetoric matches that of his films. “I am not sure what his ideology is,” he adds. But he has remained steadfast in his opposition to Y S Jagan Mohan Reddy and his love for Che Guevara. However, his stand on the BJP has changed with every election, says Srinivas.

Kalyan would often attack the saffron party and the TDP over their failure to deliver special category status to Andhra Pradesh. But the union government’s invitation to Kalyan and Naidu for the consecration ceremony of the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya early this year indicated a revival of an alliance. The BJP has not been able to win a single seat from Andhra Pradesh and will hence, be looking to make some headway into the state with the help of Kalyan, whereas the latter would require a national party’s assistance to stay alive.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

“Nenu time ni nammanu, na timing ni nammutha! (I don’t believe in time, I believe in my timing),” “super cop” Kalyan’s dialogue in his 2012 blockbuster Telugu movie, Gabbar Singh, a remake of Salman Khan’s Dabangg, would probably be fitting to describe the current political situation of his party that has allied just in time with the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA). But will the timing be in their favour this time?

(This appeared in the print as 'Lights, Cinema, Politics')