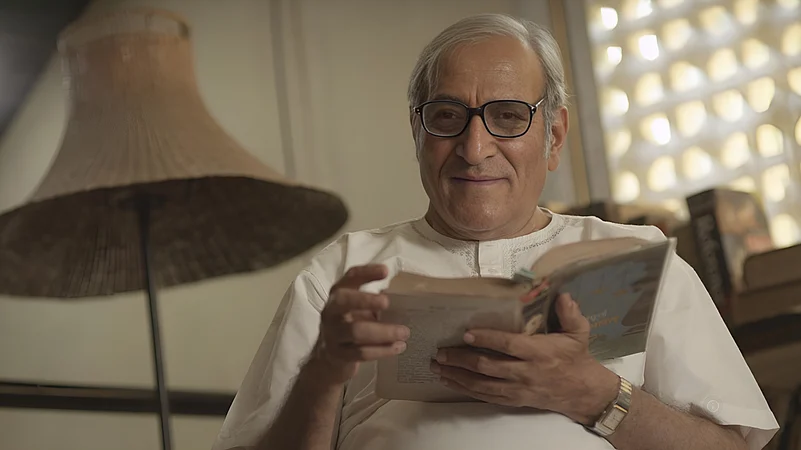

Veteran actor Mohan Agashe has many facets. As an actor, he has worked with renowned directors of the parallel cinema movement and is well-known for his role in the play Ghashiram Kotwal (1972). He is also a psychiatrist and has produced several films that address mental health issues. He is the former Director of the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII). Arvind Das recently spoke to him about his life and career. Edited excerpts:

Let’s start with your theatrical journey. Do you remember your first acting experience?

For me, acting was like it is for any child—an activity we all go through as we grow up, around the age of three, four, or five. We all mimic, whether it’s our teachers, our fathers, etc., as a form of communication, not professionally. Acting is in my own nature. It’s one of the natural ways of learning about oneself and the world. The school I attended had some teachers who were also good at dramatics. I was also lucky because around the same time, Sai Paranjpye and Arun Joglekar had started a children’s theatre in Pune. They would hunt talent for a program called Balodyan, a Sunday show on All India Radio (AIR), Pune, in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Before that, during Rabindranath Tagore’s birth centenary, I played the character of Amal, a terminally ill child, in the play Dak Ghar. His only way of interacting with the world was through a window, where he would make friends.

Was Dak Ghar for AIR?

No. You see, Maharashtra has a strong tradition of amateur theatre groups. For example, Vijaya Mehta started with a group called Rangayan, Satyadev Dubey with Theatre Unit, and Bhalba Kelkar started with the Progressive Dramatic Association. The group I was involved with was Maharashtra Kalopasak, and this was for a public show in Pune. Around the same time, I also used to go to Balodyan programs on Sundays. Gopinath Talwalkar, Sai Paranjpye, and one gentleman named Neminath were involved. I acted in Sai’s play Nirupama Aani Parirani, which was later made into a film. Mr Vinay Kale made a film based on Sai’s script in 1961, where I played Pinocchio. That was my first film.

So, you became an actor first, then a doctor, and later the Director at FTII?

What I want to say is that anyone who becomes an actor later in life actually starts in childhood. They may not be on stage, but they act at home...

You were born in July 1947. Your life started with independent India. How do you see your and India’s journey?

This whole thing about thinking and intellectualising everything is a new mechanism. Until I went to medical college, I wasn’t analysing things—I was just doing them. I’m not one of those who are intellectually very bright. I think the first sign of getting old is when you start looking back on your life.

How did you manage theatre while attending medical school?

After school, I continued acting until pre-medical. In my first year of medical college, I met Jabbar Patel, a well-known name in theatre, and theatre became as serious an activity for me as my medical studies. I acted throughout my medical career and even joined an amateur theatre group, the Progressive Dramatic Association. My life in psychiatry and in theatre/cinema were like two parallel streams.

And how did you start acting in Parallel Cinema, beginning with Shyam Benegal’s Nishant [1975]?

He saw me in the play Ghashiram Kotwal. I played the character of Nana, which I enjoyed performing for twenty years [from 1972 to ’92]. Ghashiram was like a school for me. It took me across the country and abroad, expanding my horizons. By 1975, it had become a milestone in Indian theatre. It was invited to more than 20 international festivals, and we participated in 12, with a total of 61 performances. There wasn’t a person in the film or theatre industry who hadn’t seen Ghashiram.

Recently, I saw Manthan [1976] in the cinema hall when its restored version was released and I was surprised to see you playing a doctor’s role in the movie.

Yes, I started Parallel films with Benegal. I was put into that orbit. Because of my love for psychiatry I didn’t move to Mumbai like others. I did one or two films a year. I acted in [movies by] Govind Nihalani, Jabbar Patel, Gautam Ghosh and Satyajit Ray’s Sadgati [1981]. It was just a coincidence that in Premchand’s story [Sadgati] the name of the Brahmin is Ghashiram. So, while reading the story he might have made a connection with Ghashiram.

What kind of relationship did you share with Ray?

He was great, I don’t argue on this point with anybody. Although Sadgati is only 52 minutes long, it gave me enough time to know why Ray is Ray—and why he was miles ahead of others. There may be people in the film institute [FTII] who thought that Ray was not great, Mani [Kaul] was great but that’s their limited thinking. Even though I acted in Mani’s film Ghashiram Kotwal [1976], it didn’t run for three days. Those filmmakers didn’t care whether people liked their films or not. In Mani and Kumar Shahani’s films, characters don’t talk like human beings, they talk like props.

But Mani Kaul’s movies Ashadh Ka Ek Din [1971] and Duvidha [1973] were appreciated a lot…

Ashad Ka Ek Din is based on Mohan Rakesh’s play. Mani only transformed what was written in words into an audio-visual medium. A lot of credit goes to the writer also. Duvidha I liked. Mani wanted to make films which he wanted to make. He was not bothered about anything else. [In Ghashiram Kotwal], he got Vijay Tendulkar to write a beautiful script using the play as a basis. It was completely different from the play; he just used excerpts from it. If you get any meaning out of it, honestly, tell me. Dr [Shreeram] Lagoo once said, “I never thought in my life I couldn’t understand a film in Marathi. Ghashiram is a film which I don’t understand.”

You acted in Prakash Jha’s films, too. What was that experience like?

Yes, I did. He has made socially relevant films. He made three films against the backdrop of Bihar: Mrityudand [1997], Gangaajal [2003] and Apaharan [2005]. These are very much related to the current situation. So, I enjoyed doing that. You know, nobody bought his National Award-winning film, Damul [1985]. Nobody saw it. He got frustrated and went back to Bihar. When he came back he said I will tell my story but use the language of Bollywood. He learnt a lesson and made Mrityudand.

You acted in mainstream Bollywood films like Trimurti [1995], Rang De Basanti [2005]...

See, I don’t differentiate. What I definitely know is there is a parallel cinema and there is a popular cinema. I am for cinema beyond entertainment. Recently I saw Laapataa Ladies [2024], Badhaai Ho [2018]. These are excellent films. Now, Baahubali [2015] is influencing Bollywood…

How do you see the rise of OTT and giving space to a new crop of filmmakers?

In one way, OTT is good, but initially when OTT came they used to acquire/buy films from talented filmmakers. But now they have started producing their own content. Again, individual filmmakers are not able to make films they want.

Coming to Marathi cinema: You’ve acted in Devrai [2004], Astu [2013], Kaasav [2017]—all of which deal with mental health issues. Can you tell us about your association with these films?

I didn’t just act in them, I also produced them. I like cinema that makes you think. I’m fond of such cinema. These films were made by Sumitra Bhave who was not a filmmaker to begin with. She was a social scientist. When she realised cinema was a more powerful medium than a book, she learnt filmmaking. She made films which made you think. She didn’t make films like David Dhawan or Subhash Ghai. So I thought I can use these films to promote mental health education in the general population as well as those who practice health science. Mental illness, psychiatry are made fun of in popular cinema. Taare Zameen Par [2007] was different.

You’ve been based in Pune. How has the city influenced your creative journey?

For me, Pune is only that Pune which existed when I was a child. Rest of it I don’t consider Pune. It’s no longer cultural Pune. I have lived here for more than 74 years. It’s become a cosmopolitan city. If you speak Marathi people will look at you strangely. Pune has lost its identity. I once went to the municipal corporation to get the death certificate of Pune!

Arvind Das is Professor and Director of School of Media and Journalism at D Y Patil International University, Pune.