Gradual growth of characters, complexities at every turn reminiscent of real life, people as grand and low as they exist in the real world. Understated, and grim, but eventually the sun decides to rise in its full glory.

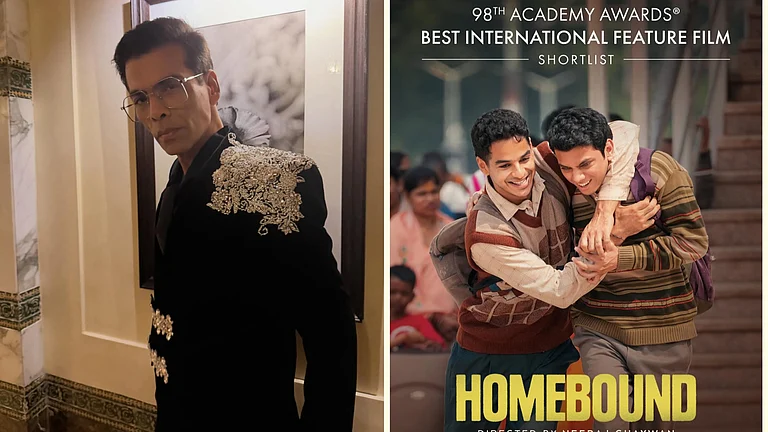

In April this year, it was the only Indian film to be selected at the International Beijing Film Festival and swept the highest number of awards -- Best Director, Best Actress and Best Cinematography, more than any other participating film. Last year, ‘Stolen’, directed by debutant Karan Tejpal was the only Indian film to be selected (World Premiere) at the Venice Film Festival after a three-year hiatus. While it may be hitting three festivals every month even now (Shanghai, Transylvania, Japan), it is yet to see the light of the day in India. “It has had an excellent international run, but I admit we are still really struggling to find our feet with sales in India. Of course, I am confident that someone will pick it up here, but well, it has not happened yet,” Tejpal tells IANS.

In ‘Stolen’, two urbane brothers from a well-to-do family witness a baby being kidnapped from an impoverished mother at a railway station in rural India. The younger one played by Shubham, guided by moral duty, convinces the other (Abhishek Banerjee) to help the mother (Mia Maelzer) to a perilous investigation to find the baby. Drawn from real-life incidents, for example, when two youngsters fishing in Assam were lynched as the villagers thought they were child kidnappers, Tejpal reveals that he started writing the film in 2019, and was later joined by Agadumb and Gaurav Shingra at the writing desk.

Then Covid hit and they were left floundering for four years. The film was ultimately shot in January and February 2023 and had its World Premiere in Venice on August 31. Like many other Indian films that have done exceptionally well in festivals abroad, including the recent Cannes, theatrical release in India remains a distant mirage. The director feels the biggest challenge lies in convincing the audiences to come in to watch these films. “You know, ultimately the government needs to step in and provide subsidies, and create an ecosystem to encourage these films to get a theatrical release. Do not forget, we are competing at the same level as the big-ticket films. Most people do not come to see our films for they know that they will be screened on an OTT platform soon,” laments the director who is now writing the screenplay for a Mira Nair film. He however feels that lower entertainment taxes and special theatres like in Europe and America can save the day for such movies. “This is how they have managed to keep that side of the industry alive -- realising its importance.”

Tejpal opines that successive governments have failed to figure out how cinema can be a major soft power. “Here, it is just a side industry, Look at South Korea - around 40 years back, they started investing in cinema, dance and music, and now have almost become the cultural gatekeepers of the world. They set up schools, theatres and universities for the arts. Maybe some decades back, we had a healthier ecosystem when NFDC was active.” Talking about ‘Stolen’, Tejpal says their research reveals that child kidnapping is one of the highest-rising criminal enterprises in the country. And up to 50 to 60,000 kids go missing every year, which is like 150 children a day. “The worst hit are the lower economic strata of the society, the extremely poor with no access to education, who do not know how to approach the Police and other social organisations. They are farm labourers or daily wage farmers, and these criminal gangs have figured out that they can very easily steal these children and get away with it. They are like goods to them because they are using them for slavery, prostitution, illegal adoption, illegal organ trade.”

An avid reader, Tejpal studied various research journals on child kidnapping, vigilantism and surrogacy. “Once Gaurav came on board, we did extensive on-ground research where we met cops and journalists who have been following these stories for decades. Both of us visited villages where such incidents had taken place. We also met several perpetrators, who of course did not agree to their crimes,” says the director who has been an assistant director to Rajkumar Hirani, Prakash Mehra and Vinod Chopra.

He however adds that they were not able to meet any victims. “While in my film, I have taken the softer route where the child is finally found, in most cases, it does not work out that way. Through their actor Mia, they accessed the surrogacy hostels where 40 women were living together as surrogates. Some of them had been surrogates two or three times in their lives. “I am talking about pre-2021 before the government passed a law against it,” says the filmmaker who moved to Goa during the Pandemic. Stressing that he is always deeply involved in the writing aspect and that is the only way he gets into a project, Tejpal says he has mostly learnt on the job, though for a year he moved to New York to do a course at the New York Film Academy in the US. “More than learning the craft, which anyway, I believe that as a director, you can only hone and not really ‘learn’, the time spent there opened my eyes to World Cinema, something I did not know much about. Therein I started my education by watching and reading,” he remembers.

The director who looks up to the works of Iranian filmmaker Asghar Farhadi and Japanese director Hirokazu Kore-eda, feels everyone has their own personal style, voice and vision, thus there cannot be a set curriculum for teaching cinema. All set to start his next directorial venture, titled ‘Nisar which is set in a small village in Haryana and revolves around honour killings, he says it is Romeo and Juliet turned on its head. “I have carried this project for more than 10 years in my head. Shockingly, we live in a society where young, do not have the freedom to love, and things can go to the extent that they can get killed for doing that."

In his next, the star-crossed lovers, make several sacrifices and make life-altering choices. make life-altering choices. “When they are faced with a choice to die or to kill to survive, unlike normal circumstances, here the couple end up murdering the boys' brothers and escape. Everything happens in a ‘dark space’, a space I find very enigmatic. Deeply believing in the power of genre filmmaking, where one can use the genre and the excitement, and ‘entertainment’ and hide within its folds what he wants to talk about, Tejpal says.

“The moment I step out of my house, so many stories encounter me. How can I not tell them, but in my way,” stresses the director who writes screenplays for others whenever he needs a break from direction. Believing that every film should be a ‘cinema of conscience,’ he concludes that he tells stories that affect him deeply.