A woman in a pink bikini holds a hose in her hands, her breasts exaggerated, her buttocks protruding in a car wash hand-painted ad in Dominican Republic. The car stands by her waiting to be washed. Juxtaposed with it is another sign from another country. Of a car wash facility in Goa shot in 2003. Here, the car stands bereft of any such add-ons. It is just a car wash.

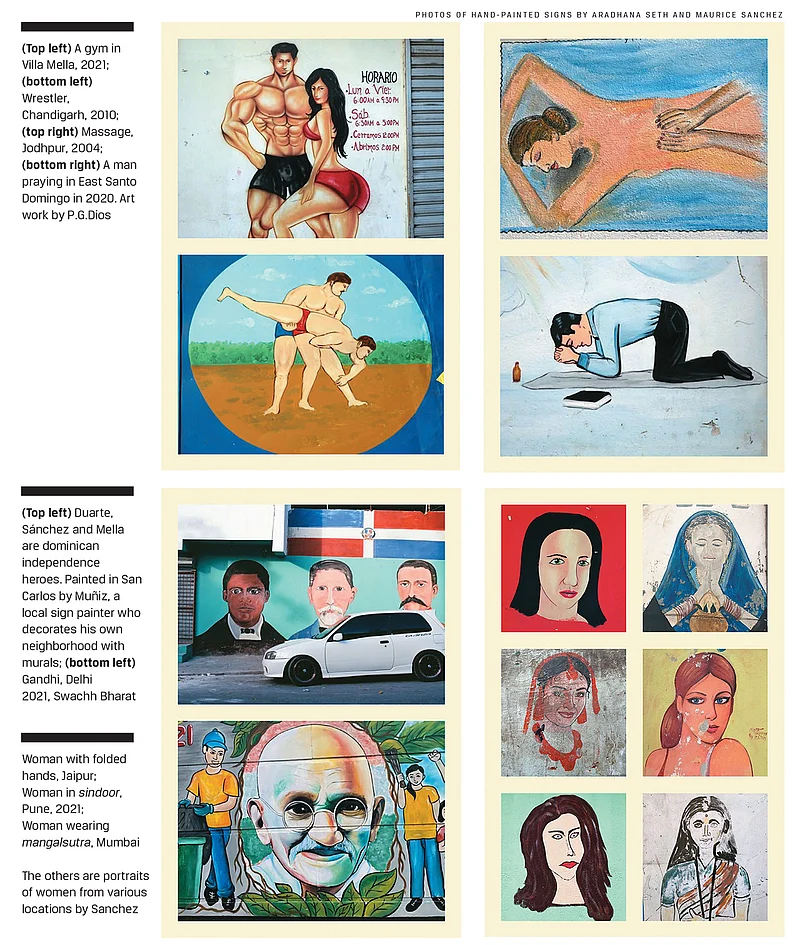

In a collage, there are six faces in one frame. Of women from the two countries arranged in three rows. While the eyes of the women from the Dominican Republic have a certain defiance in them as they engage with the world looking straight out of the frame, the Indian counterparts have a demure gaze. The bright lipstick of the other contrasts with the ghunghat of Indian woman, the hair-in-the-wind of the other is next to the one who sports a mangalsutra and sindoor to mark her marital status. The features of the women correspond to the prevalent ideas of beauty, their complexion. Aspiration and tradition mark the frames.

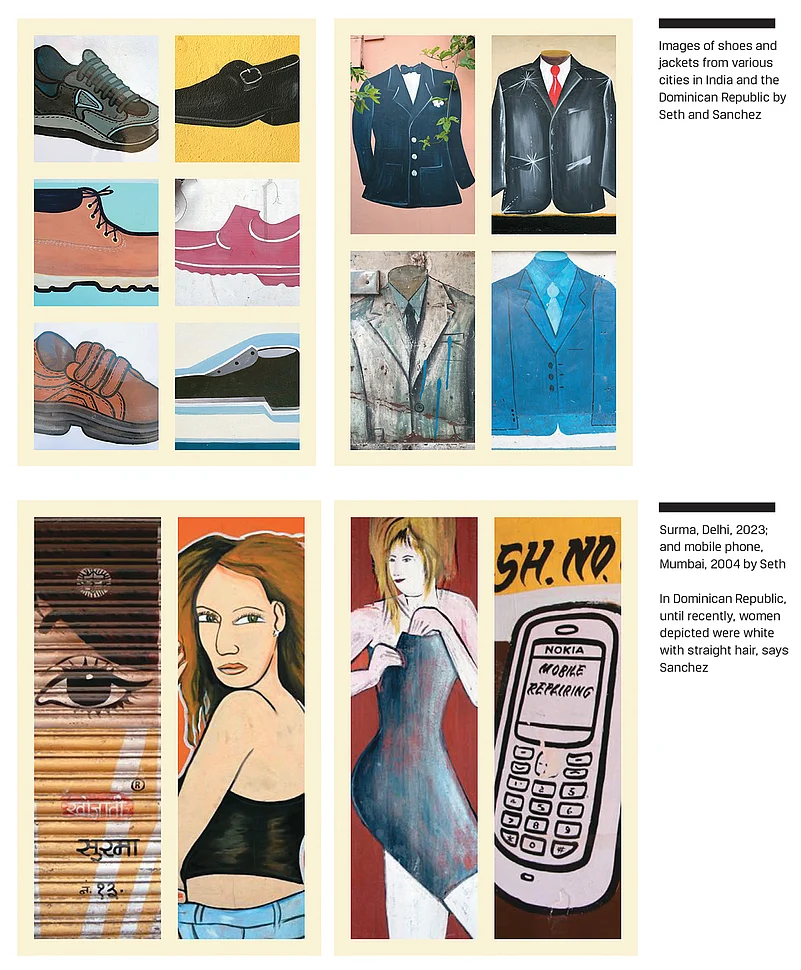

There are many such juxtapositions that assert the role of the vernacular in this exhibition initiated by the Embassy of Dominican Republic in India under ambassador David Puig, featuring the photographs of hand-painted signs by two artists—Aradhana Seth in India and Maurice Sanchez in the Dominican Republic—at the India Habitat Centre in New Delhi. The many frames curated by Seth and Sanchez are representative of the visual language of streets in the cities of the two countries from the ‘80s to now. Kitschy, colourful and bold in their pitches and their takes.

It is then a reflection of a place and its people, their beliefs and their traditions, their sub-contexts within the larger framework of a country and society through an art form that belongs to the streets.

The many hand-painted signs are from two different cultures, two different nations and yet, the vernacular connects them, and the ways of seeing and presenting bind them. Dominican Republic and India are those two places from where the signs come from, they are advertisements of products, repair shops, school signs and landscapes. The two photographers Seth and Sanchez have archived them to explore autonomy and ambition within cultural and economic contexts where the vernacular space provides empowerment to individuals.

In their essay about the show on the hand-painted signs from the two countries, Rahul Srivastava and Matias Echanove, co-founder of urbz, an experimental action and research collective specialised in participatory planning and design, invoke collective memory connected to the local, working-class lifestyles. “Bringing Seth and Sanchez’s photographs into one space collapses other seemingly impossible worlds—two countries with vastly incomparable scales in every quantifiable possibility, from geography to demographic. Yet they sit beside each other quite seamlessly,” they write.

In the absence of women in the advertisements of one and the presence in the other, there is the stamp of patriarchy. One hides, the other overexposes. Other contexts come into the play like religion and color.

Draped in a green cloak with golden and red borders, with a divine light surrounding her, a black Mother Mary holds a black baby Jesus dressed in a reddish robe in one frame. This was spotted by Sanchez at a Santeria shop. The baby Jesus sports a colorful headgear similar to his mother and holds a book in his hand, which could be the Bible. This frame is an interpretation of the vernacular version of Jesus against the imposition of the narrative of a ‘white Jesus’.

Parallel to this frame is the image of an Indian Goddess. A garland of human heads rests on her chest, the red around her mouth indicates blood and her tongue is rolled out. The third eye on her forehead is open and a string of hibiscus flowers hang from her crown. She is the Angry Indian Goddess Kali. She is brown. Not blue or white. That’s a marked departure from prevalent representations. The streets have their version to counter any impositions. That’s a political act of reimagining and reasserting even when it comes to gods.

The images of a barber shop featuring dark skinned men with curly hair bring about the distancing of commercial art from the ‘white supremacy’ approach. Until over a decade ago, hand-paint signs only showed white and lighter skinned people with straight hair, says Sanchez. But that is not the reality of a Caribbean nation. Pointing out the contrasting difference of ethnicity of the people in his country and the paintings on the walls. “Now you can witness dark-skinned, curly-haired people in this art form, reflecting an acceptance of Dominicans that they are beautiful,” he says.

Both artists encountered the operational ‘male gaze’ in their respective countries in the hand-painted signages. Sanchez met only male sign painters in his country in the last 25 years and in his photographs, the presence of women, even in a car wash advertisement, is also a reflection of the role and function of gender in a society. Women painted in a hyper-sexualised manner in the Dominican Republic signs feature enlarged breasts, bikinis, cleavages, and curves.

In Seth’s case, in the past three decades she spent photographing these hand-painted signs, she has never met any women who were sign painters. In a patriarchal society like India, the gender representation is unbalanced. The sign painters are men.

“The street signs tell us a great deal about our daily life, about the advertising of various goods and services. For me, they are the fabric of the cities, towns and villages we live in. It’s a place of expression. The signs tell me, what kind of neighborhood it is, how they live and dream,” says Seth.

Both photographers are not just archiving a visual culture that is now almost lost. They are also recording urban histories of those who created the signs, the ordinary people whose lived experiences informed their creativity. They bring forth the “native attempts” at assertion, which runs against the kind of aesthetic that belongs to the elites in a post-colonial world, the aesthetic that art galleries promote and curate. This is resistance itself. An ambitious one that chronicles a vanishing world.

Vinyl and digitally printed posters have been replacing the hand-painted signs. In a way, it is also a narrative of belonging, a defiance against the homogenisation of everything and a celebration of diversity, of the vernacular and of their ownership of places.

In a set of frames for the sale of chickens the contrast is noticeable.

The Dominican chicken are personified, emasculated and in one frame even carries a gun. In another, a chicken holds a female chicken in a short dress by her waist. In a third image, a woman in bikini rides atop a chicken. The Indian chickens are realistic and functional. They are attractive creatures detailed with beautiful feathers.

In the Dominican Republic, a sliced fish head features in a frame, its reddish flesh separates it from all other colorful whole fishes. In another frame, the chopped head of a pig rests on a tray surrounded by lemons.

While in India a whole fish is painted on a wall and a pig stands on its four on a farm. “When it comes to animal products, some Dominican images appear violent and humorous. In contrast, in India we tend to project ourselves as less violent while selling the same product,” says Seth.

That’s how the streets speak. They speak of aspiration and rebellion. The unappreciated and ubiquitous everyday written text that draws from linguistic landscapes where street signs inform social roles, dissect diversity and stamp identities of the working class, their creativity and innovative approaches to mark their presence.

The streetscape is a visual representation of a culture and everyday life of people, an alternative way of looking at history besides the monuments that loom large in the backdrop of a city. The engagement with a place is through its streets.

While the hand-painted sign has not been historically considered as an artistic practice, it is a documentation of vernacular design practices that provides an insight into the imagination of people, which is both political and social, and a reflection of how people transcend reality.

This is also a story of agency, of understanding and a reminder that art is not bound but free and full of possibilities like the idea of the vernacular. Like this exhibition.

(This appeared in the print as "Language of the Street")