In an inimitable career spanning nearly a demi-decade, Mrinal Sen gifted his viewers a diverse set of cinematic gems that continue to be discussed, analysed, and debated over until this day. Along with Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak, Sen is clubbed into the holy troika of Bengali filmmakers, who brought international acclaim to Indian cinema. It was Sen who heralded the Parallel Cinema strand, also known as the "Indian New Wave", with his Hindi-language debut, Bhuvan Shome (1969). With 27 features, 14 short films, and four documentaries to his credit, Sen's legacy as one of the country's foremost filmmakers remains beyond question.

Sen is lauded more for his politically-charged films, especially the famed Calcutta Trilogy, than his personal dramas, some of which are no less riveting. An often overlooked work in his rich oeuvre is his penultimate film – Antareen – a hypnotic, minimalist drama that is a testament to Sen's exemplary command over the medium. Emptiness and loneliness are motifs that challenge Sen's protagonists more often than not, and in no other work of his is this existential despair as piercing as in Antareen. The 1993 film starring Dimple Kapadia and Anjan Dutt, won the National Award for Best Feature Film in Bengali and deserves to be counted among Sen's best works.

Based on Saadat Hasan Manto’s story Badshahat Ka Khatma, the film delves into the isolated lives of two strangers who develop a unique bond over telephonic conversations. Anjan Dutt’s nameless character is a writer who tries to work in solitude in a friend’s ancient mansion in Calcutta. The partly dilapidated house with its damaged walls and broken pillars evokes a sense of nostalgia; as if they confine memories of the yesteryears and those of the previous inhabitants. It has been beautifully shot by Sashi Anand, who doubles as the music director, providing a haunting and melancholic background score that lends the film tremendous depth. Dutt’s character seeks literary inspiration from Rabindranath Tagore’s short story, Hungry Stones, in which the protagonist occupies a similarly desolate palace, built centuries ago by the Mughals.

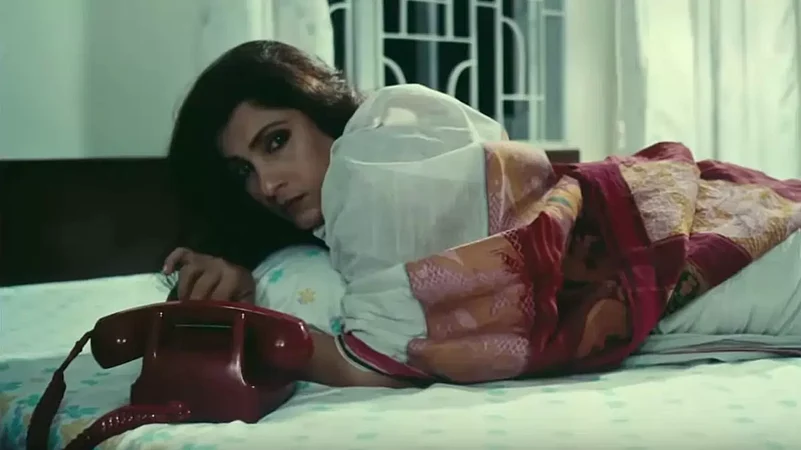

Dimple Kapadia plays the role of a lonely, neglected housewife who randomly telephones strangers at night to ephemerally escape her excruciating loneliness. She is more of a mistress to her husband, who lives with someone else. Caged in a prison of her own, one night she accidentally telephones the old mansion where Dutt’s character is staying alone. And, thus begins a virtual relationship between the two strangers, leading to several phone calls in the coming days. Her character’s predicament bears resemblance to the slave girl of Hungry Stones, who has been bought by her master. Kapadia’s penetrative stare in front of the camera (a trademark in Sen’s movies) invites the viewer to confront the emptiness and helplessness of her character. What began as an amusing engagement over the phone for Dutt’s character, gradually turns into sympathy and genuine concern for the lady. The open-ended climax doesn't reveal if he ends up "rescuing" the woman or if they meet the tragic fate of the protagonists of Hungry Stones. Considering the ill-fated endings he is mostly associated with and the climax of my favourite Sen movie, Khandhar (1984), which also juxtaposes the inner turmoil of the protagonists with their crumbling external worlds, my inference tilts towards the undesirable.

Sen’s filmography can be divided into two phases. The first is driven by hope, despite the brutality of an unjust world. His earlier films championed the need for change and revolution in society. Whereas, towards the twilight of his career, Sen’s scrutiny turned over individual lives rather than socio-political didacticism. Sen was under no romantic illusion that cinema had the power to transform society, as is evident in his following remark: "I don’t agree with Godard when he says that the cinema is a gun. You can’t topple a government by making one 'Potemkin'. You can’t do that with ten 'Potemkins'. All you can do is create an environment in which you can discuss a society that is growing undemocratic, fascistic.” However, the decadence of society, erosion of values, and the failed Marxist movement did lead to cynicism seeping in, possibly bringing along loneliness as a companion. Perhaps, the lonely characters in his later films reflect the existential void he was experiencing in his personal life. But one thing that we are certain of is that the void left by Mrinal Sen in the world of cinema can never be filled.