If you have read Salman Rushdie, you will know that he’s forever nostalgic about Bombay, his childhood fairyland whose magical dust has fuelled some of his finest novels, most famously Midnight’s Children. He lovingly calls his former home “my lost city”. In Maximum City, Suketu Mehta writes, “Each Bombayite inhabits his own Bombay.” And long before these modern-day bards there was Saadat Hasan Manto, whom author Aatish Taseer has described as the quintessential “Bombay writer”. Literature, as we can see, has always had a great love affair with Bombay. But the city is also home to Bollywood, which has tried to capture its throbbing pulse and never-say-die spirit in its own way. According to Hindi cinema, the maximum dreams of the maximum city are often matched by the maximum nightmares.

I am a Mumbaikar myself, and to be one is to navigate two opposite worlds at the same time. One is that of the poetic fantasy—or the “beautiful forevers”, as writer Katherine Boo puts it—whereby we try to romanticise its ‘City of Dreams’ aspect that reflects endless ambition, enterprise and Bambai se aaya mera dost swag. The other is its more realistic manifestation, a megacity of hard-knock existence where dreams come to die. (Watch Gharaonda, a 1977 tale of typical Bombay struggle in which lyricist Gulzar reserves his most plaintive verses that define a more realistic side of the Mumbai experience). Here, people lead “lives of quiet desperation”, to borrow from Henry David Thoreau. This dichotomy has been a recurring motif in many Hindi films, particularly those that have attempted to celebrate Bombay/Mumbai as a character rather than using it just as a fanciful backdrop.

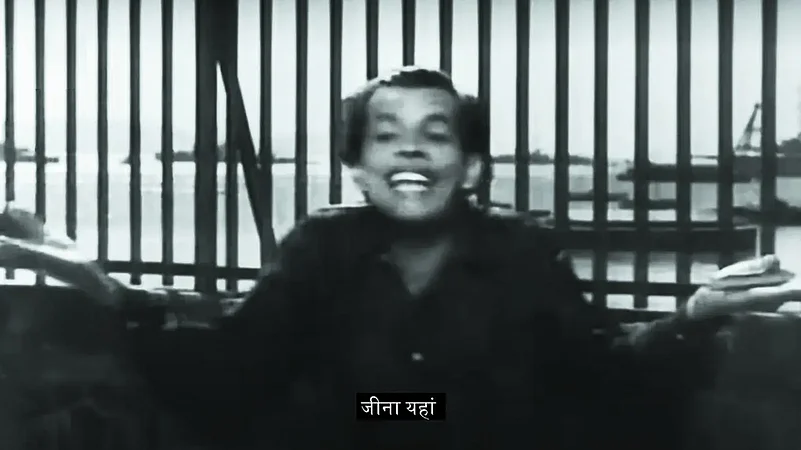

But then, every movie set in Mumbai these days claims to show the city as a character. Only one as rare as the Dev Anand starrer Taxi Driver (1954) has the gumption to make that assertion explicit by cheekily slipping in ‘city of Bombay’ in its opening credits alongside other ‘guest artists’. Like many Dev Anand films, Taxi Driver is as much an ode to the idea of romance as it is a love letter to Bombay. The most unusual thing about the evergreen Anand films is that they depicted Bombay as a lair of crime and shallow glamour. Though inspired by Hollywood noirs, they sweep you into the world of urban underbelly with distinctly Indian twists. With their moral ambiguities and focus on rapidly changing social and cultural mores, they portray a city at the cusp of modernity. In them, the post-Independence optimism is very much in the air but often, the protagonists find themselves greatly torn apart by the corrupting influence of the metropolis. Anand’s other iconic hits of the era like Baazi, CID —best known for the city’s de facto anthem Yeh hai Bombay meri jaan—and Kala Bazar are perfect examples of what you might call the ‘Bombay films’. For old souls, there’s an unmistakable joy in seeing the then-Bombay at its charming best in these golden-era classics. So much has changed about the city’s character since and yet, much else remains the same. For example, one of the pleasures of watching the Taxi Driver song Jaayein toh jaayein kahan on YouTube is not just to hear a young Lata Mangeshkar’s nasal pitch but also to see an almost pristine Worli sea face where the only time you spot a crowd is when a throng of onlookers gathers behind, perhaps to catch a glimpse of Dev Anand. Today, the Worli sea face neighbourhood is a different beast altogether, though some of the old bungalows are still standing, biding their time as the last surviving link to its idyllic past.

If Dev Anand’s Bombay was a den of gambling, vices and vamps, his contemporary, the inimitable Raj Kapoor’s Bombay was worse—cold-hearted and indifferent. The Bombay of Shree 420 (1955) is all maya (as exemplified by the character of Nadira) and Kapoor’s innocent fool quickly gets sucked into a whirlpool of riches and glamour. The beggar, who meets him at the film’s opening, puts it bluntly when he says, “Yeh Bambai hai mere bhai, Bambai…yahan buildingein banti hain cement ki aur insanon ke dil patthar ke.”

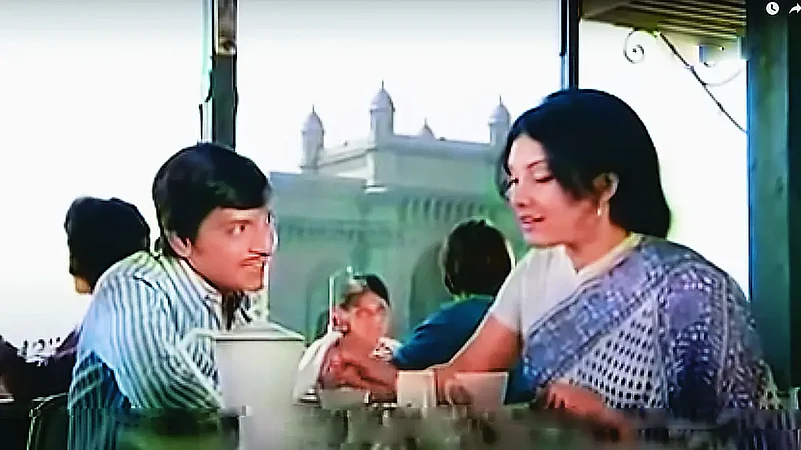

Bombay has been a muse to filmmakers from the 1970s and ’80s, too. The city has been immortalised in mainstream (here’s looking at you, Manmohan Desai and Prakash Mehra), middle and parallel cinema alike, but not always in a tone that suggests celebratory or larger-than-life. Take Basu Chatterjee’s films. Khatta Meetha and Baton Baton Mein are predominantly set in Bombay while Rajnigandha includes the lovely song Kaeen baar yunhi dekha hai shot in a cab as it meanders through Bombay’s streets. But it is in his endearing Chhoti Si Baat, starring Amol Palekar and Vidya Sinha, that Chatterjee successfully encapsulates an unhurried middle-class romance blossoming between two pure souls in a city that notoriously never sleeps. The now-defunct Samovar cafe and Jehangir Art Gallery at Kala Ghoda, Gateway of India and bus stops advertising the latest hits from the dream factory...Chhoti Si Baat’s Bombay is as quaint as it can get.

Unlike Basu Chatterjee, the Bombay found in his parallel cinema counterparts like Govind Nihalani, Muzaffar Ali and Saeed Akhtar Mirza’s cinema are more angst-ridden. Particularly Mirza’s Salim Langde Pe Mat Ro (1989) and Albert Pinto Ko Gussa Kyun Aata Hai (1980) portray the aspirations and hardships of the minorities who are being left behind as the financial capital of India gets richer and yet, simultaneously more insular. But it is Naseem (1995) that by far remains Mirza’s most personal film. It tells the story of a grandfather (played by the legendary Urdu poet Kaifi Azmi) and his granddaughter in the days leading up to the Babri mosque demolition. In a 2012 interview, Mirza told this writer, “Naseem was the epitaph for me—epitaph to an age, to a time, and perhaps, also to cinema.”

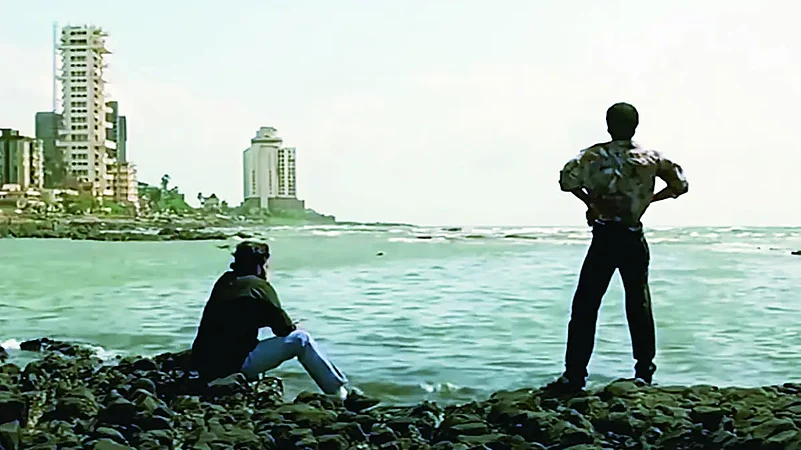

Mirza may have never made another worthwhile film after Naseem but his work seems to have influenced a generation of filmmakers. From Mira Nair’s searing Salaam Bombay! (1988) to Zoya Akhtar’s Gully Boy (2019), Mirza’s rooted, neorealist style has made him a unique voice of subaltern Mumbai. A landmark of its genre, Salaam Bombay! is a stark depiction of the under-city, hitting you with its haunting raw power and the epoch- making Ganesh Chaturthi climax that became a template for nearly every Bombay film in the decades to follow—Satya and Vaastav to name just two. Journalist Uday Bhatia, who has written Bullets Over Bombay, a terrific book on Ram Gopal Varma’s Satya, recently told a news portal, “Everyone thinks of Satya as a gangster film but it’s actually a film about living in Bombay.” Movies on Mumbai’s mafia tend to glamourise crime, making guys like Manoj Bajpayee’s Bhiku Mhatre or Sanjay Dutt’s Raghu seem like messiahs.

Instead, pay attention to the sobering wisdom of older underworld figures like Abbaji (Pankaj Kapur) in Maqbool. A desi Godfather, Abbaji recites one of the most memorable dialogues about the city in the Shakespearean tragedy: “Mumbai hamari mehbooba hai miyan, hum isse chhod kar Karachi ya Dubai nahin jaa sakte.” The other unforgettable line goes to the original Bombay chronicler. There’s a scene in Nandita Das’ Manto (2018) in which Manto is leaving for Pakistan after Partition. He’s accompanied by his friend Shyam in the taxi. As they pass by a favourite haunt, Shyam offers to settle an old account with the shopkeeper. But Manto (played by Nawazuddin Siddiqui) tells him not to, delivering the punchline of a lifetime, “Main chahta hoon ki zindagi bhar is sheher ka karzdaar rahoon.”

(This appeared in the print edition as "Mumbai Matinee")

(Views expressed are personal)

Shaikh Ayaz is a mumbai-based writer and journalist