It was a long Thursday. One that started off with the aroma of freshly baked brownies and ended with the scent of grief, of unexpressed grief. Or so I thought. That’s when my 11-year-old daughter shared the note she had written for Ankit:

“You were the happiest, funniest and the nicest. That’s what made you a lovely human being. Even though I wouldn’t understand all the jokes you adults would crack, I would just laugh along. Your smile brightened my world. I can’t believe that you are gone. You will always be in our hearts and we will always love you. Even if the others forget, just remember that I will always love you. Thoughts and prayers for you.”

I hugged her tight. Her initiation into the world of grief and despair had begun, with the demise of one of her favourite humans. There was an elephant sitting on her chest, refusing to get off. Like most of us, she couldn’t come to terms with Ankit’s death.

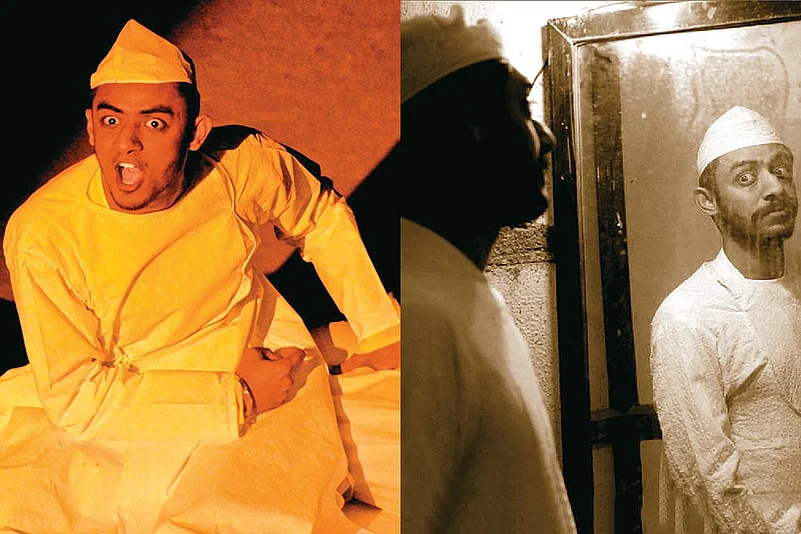

By now, my mind had become a bioscope with thoughts being played inside it through a barrage of slideshows. Some moving. Some static. I could see him swirling like a dervish, high on poetry. And then he took the form of a maypole, with colourful yardages of fabric all around him, people holding the other ends. I could see him standing under the yellow gulmohur and then sitting comfortably on the mattress, in his pristine, white, chikankari angarakha. Gandhi. Kabir. The Kabir Festival. Flashes of red, partly withered petals of the gulmohur tree interrupted every frame. I am hoping that writing this for Ankit will help me in my grief.

In 2013, I started volunteering with the Kabir Festival, a community-funded, volunteer-driven three-day cultural jamboree in Mumbai, born of like-minded people coming together to spread the teachings of Kabir and other mystic poets like Bulleh Shah, Tukaram, Meerabai et al through music and stories. An amalgamation of mysticism from all parts of the country, the festival brings together the Bauls, Malwi and Kutchi folk singers, Carnatic and Hindustani vocalists, fusion rock bands, dastangos and Sufi singers to collaborate and create under one big tent. The idea is to connect the urban audience with the mystic voices and spread the message of love, compassion and tolerance. The events are free and open to the public, and attract people from all walks of life.

In 2014, I was assigned the task of accompanying Ankit from Powai to Bandra for the early morning satsang, one of the festival’s highlights. He was already popular as the youngest proponent of dastangoi and for me this was nothing short of a fangirl moment. Much had already been written about this history graduate-turned-dastango from Delhi’s Hindu College. I contained my excitement. After all, he was an artiste, a renowned one, who’d made his way into the hearts of young and old alike, and I didn’t want to disturb or intrude into his space. But he spoke to me like we were long lost friends. He told me how the festival and the community at large were responsible for rekindling his passion for writing and how Kabir and his philosophy held a special place in his heart. That journey was the beginning of a new friendship. It was also when I began soaking myself in the spirit of the festival.

The community showed immense faith in Ankit and his art. Gradually, the festival became a platform for him to experiment with new dastans. Our interactions grew too. As a teacher and storyteller, his presence mattered a lot to me. Our discussions often revolved around his research methods. Dive deeper. Immerse. Observe, imagine and concentrate. These were his mantras. It was inspiring to see him work on his narratives. The young boy knew well what his purpose in life was. His dastans bear testimony to the fact that he was subtly confronting the issues tainting humanity. He had the knack of deftly weaving the politics of the day into his dastans. He could have settled for mediocrity and nobody would have noticed—they would still have held him and his art in high regard. But he knew there was a public purpose to his art, and presenting partly-researched narratives would amount to deceiving his audience, his hazreen.

His head would forever be brimming with ideas. Who would think of weaving a narrative around Dara Shikoh, the alienated son of Shah Jahan! Well, Ankit did. He collaborated with Supriya Gandhi and brought Dara Shikoh to life—and the audience loved it. When Norton Juster wrote The Phantom Tollbooth, he wouldn’t in his wildest of dreams have imagined a Hindustani spin to the tale. But Ankit was adamant that Milo had to travel out of that book and reach his hazreen. He had this inane ability to look for subjects that most of us are either unaware of or have conveniently ignored. His Dastan-e-Khanabadosh spoke extensively about the self-sufficient minimalistic lifestyle of the wandering pastoralists of Gujarat, Rajasthan and Uttarakhand. And for this he spent time with them, trying to understand their way of life in comparison to the settled world. He travelled with his dastans across the seven seas, taking them to Harvard and Yale. The dastango had his favourite venues too. In Mumbai, he loved performing at the Kitab Khana and The Pond Room in The Great Eastern Home.

I often teased him that his angarakha was like Clark Kent’s cape. And that wearing it transformed him from a mischievous boy with twinkling eyes to a mediaeval storyteller. He would give me that one-brow frown followed by a deep, guttural laugh. Those who knew him will vouch for his magical hugs and the purity of his soul. My mind soon raced back to the last hug. He had just finished Prarthana, a musical dastan on how Gandhi perceived death. As I hugged him, I smiled. He knew the reason.

“Kaha tha na, Kabir tak pahunchi ho, Gandhi tak pahunch hi jaaogi.”

From the little boy whose eyes popped out every time he saw Rashtrapati Bhavan, to the proponent of a dying art form, Ankit Chadha had come a long way. It is still difficult to believe that this young trailblazer’s journey was cut short in a freak drowning accident in Lake Uksan, Pune—a city that he referred to as a milestone in his career.

I know that he’s gone. It’s been a day now. I bade him farewell under the red gulmohur. But a part of me wants to believe that he is working on his new dastan and will soon be back with,

Toh hazreen pesh karte hain Dastan Jheel Uksan Ki…

***

What is Dastangoi?

An oral storytelling art form, it travelled from medieval Central Asia to Iran, then to Delhi, with the eastward spread of Islamicate culture. The word is a fusion of two Persian words: dastan and goi, the story itself and its telling. The 1857 revolt led to an exodus of artists, writers and dastangos from Delhi to Lucknow. Here, it found a hospitable ecosystem: residences, opium houses, city squares, all hosted performances. The narratives spun around warfare (razm), love (ishq), beauty (husn) and revelry (bazm), borrowing from the Arabian Nights, Rumi et al. The Indian stream introduced an element of aiyyari (trickery) and awargi (vagrancy). It faded out with the last great dastango Mir Baqar Ali’s demise in 1928. Shamsur Rahman Faruqi, Urdu poet-critic, led a revival in 2005.

(Parvathy Nair, a teacher and storyteller, is part of the Kabir community.)