In a five-century-old music form like Carnatic that increasingly revels in oscillation of notes, ornamentation of every passage comes almost by default—making the system naturally sparkling. Amid them stand a few masters, who sound (relatively) Spartan yet fascinating in their vocals while being simultaneously brainy but uncomplicated in approach. Focusing on two yesteryear veterans in the category, this column is timed in a week that marked the third death anniversary of one of them and in a year that is the birth centenary of the other.

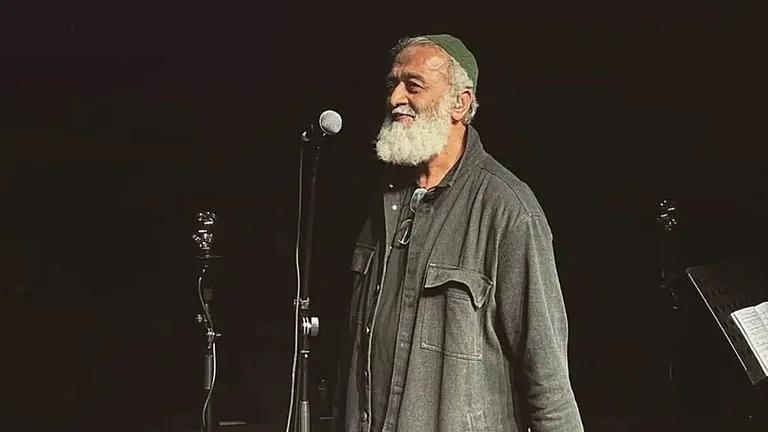

February 17 was when R.K. Srikantan died in 2014. And Dr S. Ramanathan would have been 100 in 2017 if he was alive. Srikantan was 94 when the south Indian idiom lost him, while Ramanathan died in 1988, aged 71. A combined memoir of the two exponents may not be out of place even without this topicality factor, for they shared—albeit unwittingly—certain elements of artistic commonness.

Sobriety was the performance hallmark of Srikantan as well as Ramanathan. Seldom would they stray into unfettered currents of the Carnatic stream despite the intellectual propensity to navigate the most complicated of them. Be it the introductory alapanam, the pace of the compositions, the delineation of neraval lyrics or the patterns of swaraprastaram, there was least a prospect of ostentation or over-flourish. Their concerts were led by a dignified spirit of restraint, all the same employing the loop-like Dravidian gamakas—but never in a way that disturbed their throat or the listener’s ear. Overall, their kacheris were like an unhurried journey along the calm waters of the Cauvery that always functioned as a metaphorical lifeline of classical music in those green stretches of the country’s peninsula.

For that matter, Srikantan’s village had the river passing by it in Hassan district of present-day Karnataka. The scenic ‘Rudrapatna’, in fertile Arkalgudu taluk downstate, was the expansion of the first of the two initials of the musician born in the festive Pongal time in 1920. For all its affiliation to Mysore state, Rudrapatna has had a historical link with the Tamil region, from where much of its Brahmins migrated in phases to the Kannada-speaking belt. Sengottai in today’s Tirunelveli district used to be one place from where Rudrapatna got several of its Brahmin settlers, according to records. Much recent studies by veteran musician R.K. Padmanabha say almost two-thirds of Karnataka’s Carnatic musicians have an umbilical relation with Rudrapatna (the youngest among their famed ones being [Chennai-based] flautist S. Shashank).

If Srikantan’s Rudrapatna has its tales of immigration, Dr Ramanathan was a musician who moved out of the country itself in his prime. The vocalist from Tamil Nadu had left for America, where he did his doctoral studies in ethnomusicology from Wesleyan University. That 1831-founded private liberal arts institution in Connecticut’s Middletown of Northeastern United States turned out to be the place Ramanathan taught, gaining a worldview of music before he returned to India.

Not surprising, thus that a chunk of Ramanathan’s disciples are rather young—and largely sprightly and somewhat flashy. S Sowmya and P. Unnikrishnan, in their late forties, for instance, also aren’t particularly remindful of their guru’s sub-genre. This feature, where the students carve individualistic musical niches despite being tutored under the same master, is typical of the ethos of Ramanthan’s own guru. Tiger Varadachariar (1856-1950) had an array of disciples (such as M.D. Ramanathan and the B.V. Raman-Lakshmanan brothers) who sang in different styles—S. Ramanathan was another among them.

Interestingly, both Srikantan and Ramanathan stuck to minimal use of nasal timber. Even at the top registers, both musicians employed throat as the prime duct to release wind—it isn’t a very common technique in Indian music, including Carnatic. Possibly, this property lent added temperance to the on-stage skills of both musicians. For the record, Srikantan was taught by the eminent Veene Subbanna and violinist T. Chowdiah before being mentored by his brother R.K. Venkataraman Shastri and father R. Krishna Shastri.

Srikantan and Ramanathan have had their next generation in the family continuing with the profession. The former’s son, Ruprapatna R.S. Ramakanth is an accomplished vocalist, while Ramanthan’s daughter Geetha Bennett plays the veena.