The word of those who search

for facts then act on what they find

To bring the truth and proof

to all believers rendered blind

By pious propaganda

sold as governmental care?

What if those the powers

oppose are honest and aware?

(Susan J. Bryant)

Propaganda, the word that has earned an ill reputation in the history of modernity, had an ecclesiastical origin in popular practice. Historical documents show that in 1622, the Roman Catholic Church first described its mission of propagating the religious homily as Sacra Congregatio de Propaganda Fide.

In 1627, the first propaganda institute called the Sacra College de Propaganda Fide was established in Rome by Pope Urban VIII for educating the ministers and clerics. The etymological origin of the Latin word propagatus goes back to 1560 which implies ‘natural generation or reproduction’. The English word ‘propagate/propagation’ has been used in Newtonian mechanics and other branches of physical science to mean the propagation of time or objects’ movement in time and space.

The meaning of the word ‘propaganda’ acquired a clear political connotation in the early twentieth century. The first comprehensive book on propaganda as a political tool was written by American socio-psychologist and public relations expert Edward Louis Bernays. The title of the book was ‘Propaganda’.

Bernays did not consider propaganda as entirely a negative mode of communication. For him, propaganda could be employed for propagating democratic values to the people. It’s no wonder that his book contained chapters like ‘Propaganda and Education’ and ‘Propaganda and Social Service’. He bewailed that World War I was responsible for popularly projecting ‘propaganda’ as a deplorable term.

The American communication expert R E Haibert explains how war, propaganda and media are connected over time— “The Gulf War in 1991 has been called the cable-TV war that brought CNN to world attention. The Vietnam War was called the first television war. World War II was basically a radio war. World War I was termed the first propaganda war. The Crimean War in the late 19th century was the first war covered by independent reporters on the battlefield. The 2003 Iraq War perhaps was the first-ever Internet war.” Both the theorists, Bernays in 1927 and Haibert in the new millennium, agree that the nexus between war and media helped the word propaganda to earn a malicious connotation.

In our time, propaganda is defined as a deceitful way of communication, the content of which caters half-truths and maneuvered statistics to its target audience; the form of which helps feed the hidden agenda to the people. In addition to that, mass media propaganda especially aims at manipulating the emotional loyalty of the readers, viewers and listeners in favour of the propagandists.

Propaganda, therefore, launches a psychological warfare between the propagandists and the masses where an individual’s independent reasoning of distinguishing between truth and untruth is superseded by the half-truth and misinformation convincingly conveyed by the propagandist group.

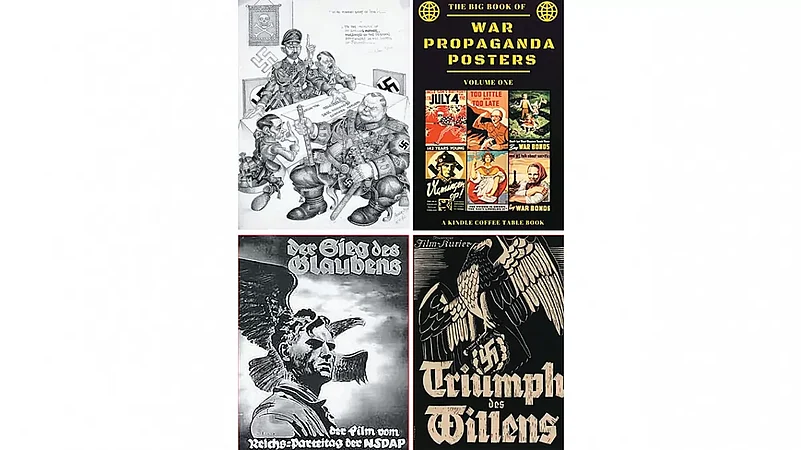

To do so, carefully building up propaganda materials often create a milieu of mesmerising effects under the spell of which one surrenders her reasons. The best examples are the Nazi propaganda documentaries made by German filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl in the 1930s. German Nazi Party formed a film department as suggested by Hitler in the early 1930s to propagate its ideology to the masses.

Having seized state power in 1933, they established the Ministry of Propaganda and Public Enlightenment. Making propaganda films was given priority by the propaganda minister Goebbels. Leni Riefenstahl, a famous choreographer and film actress, was assigned to make a documentary film on the Nazi Party rally in December 1933. But later Hitler ordered to destroy all copies of Leni’s film The Victory of Faith as the film contained several images of Hitler and the chief of Brown Shirts Ernst Rohm together.

Rohm, the Fuhrer’s competitor in the party, was eventually murdered on Hitler’s order on July 1, 1934. Leni’s second project The Triumph of the Will (1935), which documented the Nazi Party Congress held in Nuremberg in 1934, was a wonderful piece of work. The film was dedicated to the Nazi Party ideology and Hitler’s charismatic presence. Nevertheless, the aesthetic beauty of the images and Leni’s control over the craft of filmmaking were remarkable. The smooth movement of the camera, seamless editing, the grandeur of the pro-filmic objects and the use of visual motifs, mists, fire, light and shadow create a mesmerising effect on the viewers’ mind.

The film repeats the images of the symbols like Nazi flags, swastika signs, eagle statues, Nazi salutary gestures and emblems on the military uniform. Every slow circular tracking movement of the camera ends either on the Fuhrer’s figure or on the Nazi symbols. There is a continuous effort to visually establish a connection between Hitler, the Prussian glory of the past and the rebirth of Germany. The film is constituted out and out with very powerful visual spectacles.

A shorter version of the film was screened for a limited audience at the MOMA, New York, by exiled Spanish filmmaker Luis Bunuel. Among the audience were French film director Rene Clair, Charlie Chaplin and the US President Roosevelt. After the screening, Clair, horrified by the power of the film, told Bunuel not to show it again. But Chaplin’s reaction was quite different. He burst into laughter, “once so hard that he actually fell from the chair”, Bunuel recalled the moment. He might have been planning his next film.

The Great Dictator, a comical response to Leni’s propaganda film, came out the next year. Since the Nazi government could ascertain its absolute control over the German film industry, some anti-Semitic films, which portrayed the German Jews as morally degraded negative characters, were released. Several films were made to project Hitler as a Bismarck-like strongman and a savior of Germany. But no other propaganda film could touch the exemplary cinematic quality of Leni Riefenstahl’s The Triumph of the Will.

The most effective propaganda films were made by Soviet filmmakers in the 1920s. Legendary filmmakers Sergei Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov were part of Soviet propaganda cinema. After the Bolshevik Revolution, Lenin took a special interest in cinema. The film, along with theatre, pamphlet and poster, played a significant role in agitprop (agitational propaganda) mission. The ‘Kino-Pravda’ newsreels (1922-25) very effectively conveyed messages of the Revolution in different parts of the newly-born Soviet Russia. They were mainly informative with a low emotional quotient. They projected the active masses and their ordinary lives on the silver screen.

The idea of ‘mass cinema’, which the Soviet filmmakers had derived from the experience of making ‘Kino-Pravda’ came to accomplishment in Eisenstein’s Strike and October and Dziga Vertov’s The Man with the Movie Camera and Enthusiasm.

In addition to that, Soviet propaganda cinema of the 1920s endowed world cinema with a very dynamic cinematic form— the montage cinema. But the polemical and self-reflexive style that Soviet cinema could build up in the 1920s gradually lost its edge in the later decades. Stalinist Soviet Russia produced mere conventional propaganda films during World War II and after.

The success of Soviet propaganda inspired American and British propaganda for public awareness. In 1937, the Institute for Propaganda Analysis (IPA) was established in the USA. It formulated tools for critical analysis of Nazi, British, Soviet and anti-communist propaganda. They examined radio programmes, pamphlets, news reports, films, newsreels and military documents.

As World War II broke out, the USA got directly involved in the global propaganda war. Since IPA scholars were engaged in analysing domestic propaganda too, the institute’s existence and activity appeared to be a cause of embarrassment for the US authority. The institute was declared ‘unpatriotic’ by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and consequently, it was closed down in 1942. In the early 1950s, HUAC took a key role in anti-communist propaganda and communist witch-hunting in the USA.

The US developed strong propaganda machinery in the 1930s and 40s. The main objective of US propaganda was to project the USA as a liberal society and to promote ‘democratisation’ at home and abroad. As expected, the propaganda materials concealed the racism, conservatism, class oppression and violence in US society. President Roosevelt took an interest in establishing US propaganda machinery in the early 1930s. The primary objective was to publicise the economic and social reform programmes adopted under New Deal and Resettlement Administration policies.

In the film world, film critic James Agee and documentary filmmaker Pare Lorentz took the lead role in Roosevelt’s propaganda mission. The anti-Roosevelt media baron, the owner of Time and Life magazines and a fascist sympathiser, Henry Luce launched The March of Time newsreel series. Mixing the news footage with fictional elements in a technically efficient manner, the newsreels catered to the US audience with the positive images of Mussolini’s Italy and Hitler’s Germany.

However, US propaganda before the war, unlike German and Soviet propaganda, was more decentralised. There were several agencies like the Office of Military Government of the US (OMGUS), Civil Affairs Division (CAD), Information Control Division (ICD) and United States Film Service (USFS) to produce and promote propaganda. In 1942, the US government merged those agencies into the Office of War Information (OWI). The OWI framed a propaganda filmmaking policy called the Government Information Manual for the Motion Picture Industry and directed Hollywood to make films to support the USA and the Allies.

Among the celebrity Hollywood filmmakers, Frank Capra and Walt Disney took the lead role in making propaganda films. Capra’s Why We Fight (1942-45) film series became globally famous. Disney had already set up a training films unit for the US military in 1941. His animation films Der Fuehrer’s Face (1942), Education for Death-Making of a Nazi (1943) and Commando Duck (1944) were well-known anti-Nazi propaganda.

Capra’s films directly countered The Triumph of the Will and depicted Hitler as an avatar of mass destruction who succeeded Genghis Khan, Bismarck and Kaiser Wilhelm. Disney’s satirical response portrayed Nazis as megalomaniac fanatics. Hollywood cinema played a very important role in shaping anti-Soviet propaganda in the Cold War era. The Rambo films and other spy thrillers narrativised ‘commies’ as demons and the enemy of democracy.

British Ministry of Information (MoI) invested some energy in making propaganda films during the war. The films like In Which We Serve (1942), Went the Day Well (1942), Fires Were Started (1943), The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943) and The Way to the Stars (1945) were made to boost up the morale of the army and the British people.

Despite their projection of heroic images of the British army, they looked slightly defensive compared with US, German and Soviet propaganda films. In India, the propaganda newsreels produced by the British Pathe Company and British Council were circulated during the war.

Gaumont’s British News was regularly imported into India. The British Movietone News and their vernacular versions called Indian Movietone News were also introduced to the Indian audience. In 1943, the colonial government in India passed an order that at least 2,000 feet of approved war material must be shown before any screening.

In fact, Paul Zils, a German filmmaker, emerged in 1945 as one of the important figures of film propaganda in India. He had been a pro-Nazi filmmaker and a confidante of Goebbels in the 1930s. He was captured by the British army in 1941 while shooting in Bali Island and sent to Bihar as a prisoner of war.

After the war, the British government in India offered him a job in Information Film in India. Later, after Indian independence, he played an instrumental role in shaping the Films Division of India, established in 1948. Our India (1950), and Martial Dances of Malabar (1957) were his noteworthy works.

Important Indian documentarists like Fili Billimoria, Sukhdev and P V Pathy were among his disciples. There are reasons to believe that the aesthetic beauty subtly blended with a propagandist tone that we observed in many Films Division documentaries of the 1950s and 60s were the legacy of Paul Zils. Though the Films Division was mainly concerned about Nehruvian nation-building projects and the heterogeneity of Indian cultural traditions, from 1972 to 75 it produced a small number of direct propaganda documentaries deifying Indira Gandhi.

We hardly found any example in history that mainstream Indian cinema was involved in making direct propaganda films. But recently we are observing a trend that some filmmakers are showing interest in making propaganda films for the regime. The Kashmir Files (2022) and The Kerala Story (2023) are significant examples.

The films show a clear intention to vilify a religious community conforming directly to the Hindutva agenda. They repeat the negative images of the characters belonging to a minority community. The narratives are stereotyping a group of people as if all of them are ‘inhuman conspirators’, ‘dreadful terrorists’ and ‘awfully immoral’.

Propaganda movies usually claim that they are based on ‘facts’ and ‘true’ events. But the history of propaganda cinema shows that they exclude the elements which may obfuscate their agenda and at the end of all cater half-truths to the masses that help straitjacketing the intended message.

(Views expressed are personal)

Manas Ghosh teaches film studies at Jadavpur University