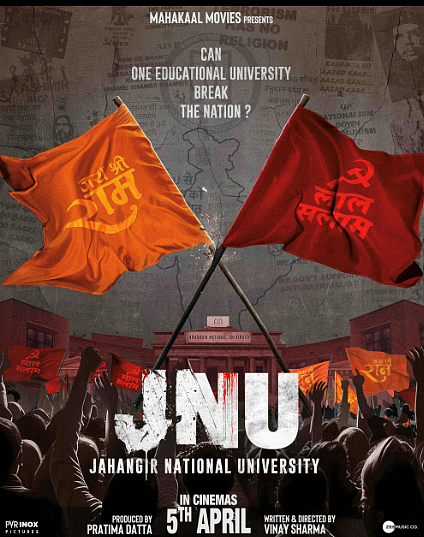

The poster screams JNU—articulated as Jahangir National University. There is a saffron flag with Jai Shri Ram written on it, placed against a red flag with the words ‘Laal Salaam’. The tagline says: ‘Can one educational university break a nation’.

The film JNU is one of the many propagandist films slated to release in the election year. While cinema has been used as a tool for propaganda of political ideologies in the past not just in India but the world over, it is critical to note that now it is being used to polarise a state that is seemingly on the verge of imploding. Propaganda is now not just limited to ideology but is also used as a means to spread hate and divide society; it is about conveniently obfuscating facts, defining the ‘other’ and converting that ‘other’ into an enemy.

In tandem with the violence and oppression we have steadily seen grow towards those very ‘enemised’ communities and institutions over the past decade, popular Hindi cinema is now becoming a tool to contribute to the culture of deliberate ignorance that we are living through. In the present time, the only narrative that has space is the one peddled by the ruling dispensation that is controlling every single kind of information that reaches people and is ensuring that there is only one perspective that matters—theirs— whether through WhatsApp, or news, or now Hindi cinema.

The ability to reason has been muted because we as a society are deafened by a singular narrative that drowns any other voice. A sane voice is defeated by decibels and is discredited thanks to the blatant, unabashed lies spread across the media. We are made to believe that only one voice and one narrative matters—that of the majoritarian, upper caste, upper class, violent, religious, Hindu men.

The agenda is multi-pronged and is being pushed at every opportunity—in narrative, language and semiotics. ‘Jai Shri Ram’, a religious outcry, has come to represent violence and hate wielded by Hindus on Dalits and Muslims and is legitimised by power. On the JNU film poster, it is proudly brandished as an opponent to an ideological discourse on humanity—that has been ‘Lal Salaam’, a leftist call in the voice of the oppressed through various fault lines of India. It has represented labour solidarities and unity of the oppressed as they resist and fight for their rights. ‘Salaam’ itself is a salutation of peace. And yet, here it has been othered; with resistance being labelled as a potential for destruction.

It is almost comical and a telling sign of our times that the regime needs a feature film to discredit one of the greatest universities of the country—the Jawaharlal Nehru University—where two serving members of the cabinet have also studied. And yet, the name ‘Jawaharlal Nehru’ has been changed. Why? Because it gives them yet another opportunity to use a Muslim name to drive another point in their agenda—to continue legitimising hate against Muslims.

The second poster has a raised fist squeezing a saffron India, with the same headline. What does this imagery mean? Is India already saffronised and ‘We The People, are to accept this? How can a university ‘break a nation’? Is resistance seditious? Semiotically, the poster and its language define the state’s perspective of and on JNU—that is not only unidimensional but distinctly damaging since it comes from reinforcing the hate-oriented ideas towards a space that fosters critical thought, equitability, resistance and active participation in politics.

The other upcoming films this year also include Accident or Conspiracy: Godhra. History in India, as taught, usually ends in 1947 with Independence and the partition. Often, many are left to understand these pivotal events in the history of contemporary, democratic India, from hearsay, or someone else’s perspective. A version told at scale tends to define one’s perception of the event itself.

While films like Firaaq and Parzania have been made in the past, they were niche and their reach was restricted. By calling Godhra an ‘accident or conspiracy’, this film attempts to whitewash the much-documented enablement of the targeted violence that was unleashed on Gujarat in 2002. Both, whitewashing narratives, and the systemic erasure of the ‘other’ are consistent behavioural patterns we see by the ruling regime (removing Mughals from history texts, demolishing mosques, changing the names of cities).

Positioning Godhra as an accident or conspiracy is a natural step to further that agenda. Altering facts to suit their narrative threatens the ability to reason or ask questions, even by viewers, which creates an even more dangerous situation. The idea is to create an angry public willing to march, blindfolded, into a divisive future that is controlled by unidimensional narratives across news media, WhatsApp, and cinema that are wrapped in aggression.

Films like Vaccine War and Article 370 are working towards bolstering the idea of work done by the regime, whitewashing its image and creating enemies out of critics. Many argue that cinema can be a fictional take, fictionalised take or even an inspired take on an event, which necessarily doesn’t have to carry the burden of objectivity that news must. However, when does cinema cease to become an independent story or narrative and become a mouthpiece of an existing thought process—that’s an imperative question to ask.

Many would argue that this is a result of not only state propaganda but also capitalist needs from films—a classic point of creating films that will be seen. However, many films like Mai Atal Hoon sank without a trace. Films now just don’t travel or are seen in their entirety. Specific clips are pushed on social media, and seen repeatedly, and that becomes instrumental in shaping thought processes, with increased attention being given to them.

Critics of the regime from the world of cinema, or even those articulating their discomfort with existing realities, have received violent threats and have faced vicious trolling and attacks on social media. While artists and filmmakers have a massive responsibility and they must reflect on their contributions towards the systemic destruction of the core values that once defined India, it becomes even more important to ask where are the collectives and the bodies that safeguard these makers and artists for them to create the films they wish to, or at least articulate their points fearlessly? There is an acute need for the viewers to build that solidarity for artists, and the recognition of what is at stake when films like the ones we are seeing in election year, finally reach theatres.

The collective ability to reason is at stake as are the fundamental dreams that once united India—of solidarity and togetherness, of learning and growing. And popular Hindi cinema now is used as a tool to slowly and steadily tear those apart.

Is there a way that while Godhra gets screened at theatres, we screen Firaaq one more time, too?