Kanhailal Heisnam, who passed away on October 6, was recognised by many in his lifetime as the master of an extraordinary theatrical language that has remained unique in the subcontinent. Throughout his life, his work stubbornly resisted capitulation to the demands of the spectacular and to the dominance of the spoken word over the bodily. Kanhailal and Sabitri (his wife, and leading actress of Kalakshetra Manipur) refused to give in to what they marked as ‘trickery’ in theatre: the presentation of extravagant gimmicks that captured the audience’s imagination momentarily but had no lingering political/emotional residue. Instead, they sought to find a language of theatre as close as possible to the innocence of a child’s wailing, a wounded animal’s cry. They insisted on a dogged simplicity in theatrical form. Kanhailal believed there was political force in the stripping away of the socio-cultural conditioning that inhibited bodily expression of pain in the raw. He preferred not to work with urban or ‘trained’ actors because so much time was spent in making them ‘unlearn’.

Yet, in the conception of his work, Kanhailal was undeniably modern, especially in his incisive understanding of the complex politics of Manipur. He also assiduously avoided superficial conceptions of the homegrown ‘authentic’ and the exoticisation of Manipuri identity, which would have certainly made his work easier to ‘package’ for the Indian mainland. In fact, his commitment to giving form to the political suffering of his people and his quest for an organic, yet obstinately simple, language of the body were tied to each other, and grew out of his experience as a Manipuri living in the shadow of the religious, linguistic and cultural aggressions of the mainland.

Kanhailal experienced this during his short stint at NSD in 1963. Soon after joining as a student, he was expelled for alleged absence without official leave. (The real problem was his inability to speak or write Hindi effectively.) For months, he remained in Delhi—aimless and too ashamed of his ‘failure’ to return home. His sense of humiliation, Kanhailal realised, had deep roots in the political condition of his people. One of his early radical critiques of the mainland’s cultural aggression over the ‘Northeast’ was Pebet, based on a Manipuri folktale about a family of birds and a rapacious cat, which he staged in 1975, during the Emergency. The cat is an embodiment of wily Brahminism, armed with Sanskrit as a weapon. The birds, on the other hand, do not ‘speak’, except with movements and sounds. Kanhailal delighted in telling the story of how Pebet escaped Emergency-era censorship, despite suspicions of subversive content, because it, in effect, had no ‘script’, except for a single Sanskrit shloka uttered by the cat in praise of his motherland. In 1980, Manipur saw AFSPA. Urban spaces now belonged more to the armed forces—the contours of proscenium theatre changed irrevocably, as did the texture of life. It is the routinisation of repression, unwitnessed deaths and sexual violence, which would dominate the lives of Manipuris for decades, that Kanhailal sought to address in subsequent productions.

Kanhailal is perhaps best known for his adaptation of Mahasweta Devi’s Bengali short story Draupadi, which he staged in Imphal in April 2000. The story had reached him via Samik Bandyopadhyay, critic and scholar. Sabitri felt Dopdi Mejhen’s story was her story, and that of numerous Manipuri women, who continued to be witness to and victims of the relentless brutality and quotidian sexual violence unleashed by the forces.

In the play’s last scene, Sabitri, almost 60 at the time, stripped on stage. The scene caused such a controversy in the intellectual, progressive and activist circles of the city, and such a war of words in the local Meitei newspapers, that the play had to shut down after two shows. Kanhailal, once again, as was his wont, refused to compromise. He would not stage the play without the nude scene.

While the Meitei community rejected the play on moral grounds, ironically, it was recognised and celebrated as a landmark production in mainland India. It was only in 2004, after the iconic nude protest by twelve Meitei women at the Kangla fort in Imphal shook both the Indian nation-state and the Meitei community, that Kanhailal’s Draupadi was remembered again in Imphal. The local papers hailed him as a seer/prophet. Still, it was not till 2014 that Draupadi was staged again in Imphal, and under considerable army presence. And around the time of his passing, a university in faraway Haryana—in the heart of the ‘mainland’—was seeing a vicious re-enactment of the whole play around the play. Such are the ironies of the political lives of artistes.

(The author is a theatre scholar, writer and actress.)

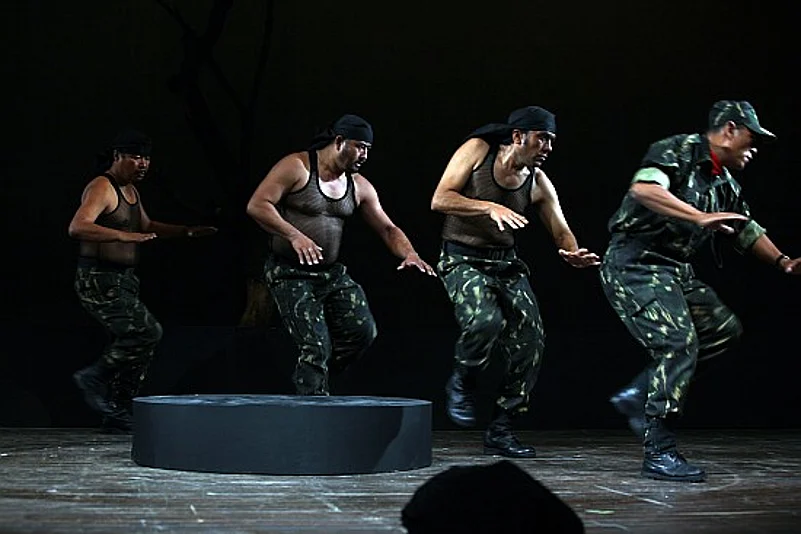

Photos courtesy: Kalakshetra Manipur Archives