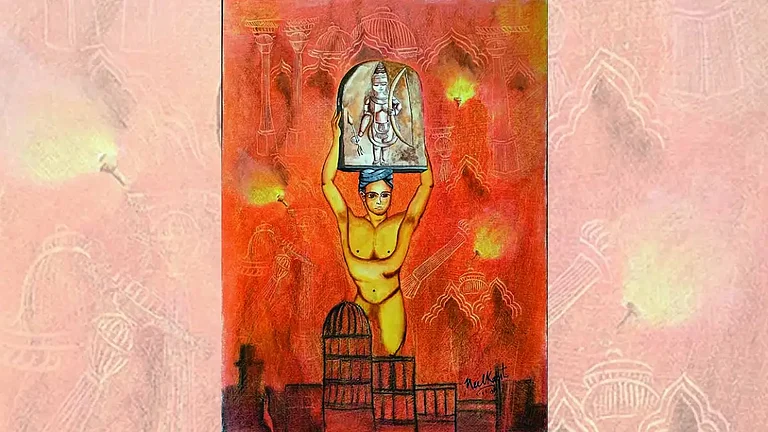

This story was published as part of Outlook's 21 October 2024 magazine issue titled 'Raavan Leela'. To read more stories from the issue, click here

A broken god lies on the riverbed. Drenched in the incessant downpour, Ragini (Aishwarya Rai) asks the god for the strength to hate. “Don’t show bad people in good light. Don’t show them as truthful,” she begs. As she wipes her tears, she senses Veera (Vikram) watching her. He smiles and asks: “What kind of man is your SP (police officer)? Is he a good man or a very good man?” “God-like,” she replies.

Veera is curious about her god and muses about his greatness.

“I feel jealous,” Veera confesses. “A burning ache deep inside. Does your god feel jealous too? No, only Veera does—the downtrodden, uncouth brute. Not a match for you, or your god-like husband. But jealousy has suddenly made me feel matchless. It makes me feel invincible. This demon of jealousy has made me all-powerful,” he declares gleefully. He looks around. Ragini has disappeared.

The scene, perhaps one of the most powerful ones in Raavanan (2010), encapsulates the multiple layers at which the film weaves in the inversion of the classic mythological epic Ramayana. The most prominent inversion is, of course, of the hero and the anti-hero.

Dev Prakash (Prithviraj Sukumaran), the devious police officer with a daunting record of encounters, is Ram. On the other hand, Veeraiya ‘Veera’, a people’s leader, is Raavan—an Adivasi rebel, fighting to avenge his sister’s rape in police custody.

But Raavanan meddles with the binaries of good and evil beyond just the narrative. It interrogates the qualities that define the figures of Ram and Raavan in the Ramayana and turns them on their head.

Envy—which is said to have possessed Raavan in the epic, leading to his downfall—becomes Veera’s strength in Raavanan. Envy births love within him, amidst the endless flow of pain and rage. He isn’t listening to his ten heads anymore; his heart has spoken.

Dev, however, has moved beyond the love for his wife Ragini. His ego has won over his heart; his vengeance leaves him unhappy, even after Ragini returns to him. The skies are mourning as the gods are broken in this universe, where the epic is upside down.

Mani Ratnam’s Raavanan is one of the rare mainstream films that has inversed the tale of Ramayana. In a country like India, messing with this age-old mythology often has dire consequences. The protagonists of this epic are worshipped in Hinduism as gods; the antagonists serve as an archetype for evil across literary and cinematic traditions. It’s not a matter of surprise then, that one of the first books banned in independent India was The Rama Retold by Aubrey Menen, which spoofed the Ramayana.

The Ramayana forms the premise of folklore traditions across the Indian subcontinent. Interestingly, this diversity has led to nearly 300 versions germinating from the mythological epic. However, the Hindu right-wing has galvanised a singular version, where Ram is the supreme hero, and Raavan the ultimate evil. Indian television and Hindi cinema have also contributed to this singularisation. Ramanand Sagar’s Ramayan, which ran on Doordarshan between 1987 and 1988, played a pivotal role in popularising Bharatiya Janata Party’s Ram Janmabhoomi movement in the following years.

Film scholars like Rosie Thomas have theorised how mythological epics like the Ramayana have served as a framework for the melodramatic structure of the Hindi film at large. In her essay, Melodrama and the Negotiation of Morality in Mainstream Hindi Film (1995), she explains: “Across the body of Hindi cinema, two archetypal figures emerge—the Mother and the Villain. In them the opposing values of good and evil are most centrally condensed.”

According to Thomas, these characters often draw from two key figures of the Ramayana—Sita and Raavan. In the moral universe of Hindi films, characters such as Ram and Sita inhabit the position of the righteous interchangeably; the ignoble Raavan, however, persists as the constant.

In contemporary times, though, there has been a peculiar appropriation of Raavan by right-wing forces. Directed by Om Raut, Adipurush (2023)—a modern-day take on the Ramayana—had Saif Ali Khan playing Raavan. While the film’s terrible production and tapori dialogues became a subject of jest on social media, Hindutva forces took great offense to Khan playing Lanka’s demon king.

The film has Raavan sporting a buzzcut, riding a dragon and enjoying a massage by pythons. His ten heads, usually arranged in a single row, appear to take the form of a floodlight. But it was Khan’s real-life identity as a Muslim that became the real bone of contention.

In a promotional interview before the film’s release, Khan stated that a more “humane” side of Raavan would be shown in Adipurush. This led to a lawyer from Uttar Pradesh filing a case against him for “hurting religious sentiments by claiming that Sita’s abduction by Raavan was justified.”

After the film’s release, actor Mukesh Khanna—known popularly for his role as Shaktimaan—questioned the director’s choice for casting Khan as Raavan, a pandit (brahmin). The Hindu Mahasabha and the BJP raised objections to Raavan appearing as Khilji and Aurangzeb, rather than a Shiv bhakt (devotee of Shiva). As misplaced as this comparison may seem, these comments stem from a more unsettling trend in recent Hindi cinema.

In 2020, Raut made Tanhaji: The Unsung Warrior, for which he was also honoured with the National Film Award. Tanhaji had Saif Ali Khan playing Udaybhan Rathore, a Rajput general in the Mughal king Aurangzeb’s army.

Though a Hindu character, the film showed Rathore as an outlier who had gone over to the enemy’s side. In costume and body language, his character is designed entirely on other Muslim antagonists in contemporary historical films, like Ranveer Singh’s Khilji in Padmaavat (2018) or Sanjay Dutt’s Ahmad Shah Abdali in Panipat (2019).

Kohl-lined eyes, black costumes, dark music, barbaric meat-eating and a mean visage—all these aspects defined the antagonists in these films. It is this trend that the Hindu Mahasabha and the BJP referred to while condemning Khan’s Raavan. In many senses then, the outrage around Adipurush conflated and consolidated the idea of the Muslim as the antagonist. This is why even Raavan, a traditional anti-hero, had to be appropriated as a brahmin.

Rabid communalism may have led to bizarre appropriations of Raavan in present times, but Hindi films have been less dogmatic with this figure in the past. Main Hoon Na (2004), directed by Farah Khan, was also a contemporary take on the immortal epic. The film, premised on an Indo-Pak peace project, had Shah Rukh Khan playing Ram, a high-profile army officer. However, the twist lay in the characterisation of Raavan—not some Muslim or Pakistani enemy, but an ex-Indian army officer Raghavan (Suniel Shetty), who was out to wreck the peace project. The film shows him going rogue due to a personal tragedy and projecting his hatred on all Pakistanis. The ultimate battle between good and evil results in an offering of peace between two countries, that have historically been embroiled in conflict since the Partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947. Thus, Main Hoon Na intelligently employs the moral universe and narrative conventions of the Ramayana to diffuse cross-border animosity at one level, and undo communal polarisation at another.

This was a period in Hindi cinema where directors were more open to analysing philosophical dimensions of the mythology from a contemporary perspective. The same year also saw the release of Ashutosh Gowariker’s Swades: We, the People. Another Shah Rukh Khan starrer, the film saw the overall trend in Hindi cinema’s obsession with the NRI (Non-Resident Indian) take a turn, as the NRI returned home. The narrative charts the journey of Mohan Bhargav (Khan), who decides to come back to India after working at NASA in the US for more than a decade. He wants to stay on to contribute actively to the collective progress of his country, which continues to be mired in poverty, illiteracy and social inequality.

In a scene where he is asked about how the US is different from India, Mohan ends up ruffling some feathers. His views on the structural problems that plague the Indian society do not sit well with the village elders.

This sequence is followed by the performance of Ramleela in the village on the occasion of Dussehra. At an opportune moment during the performance, when the qualities of Ram are being elaborated, Mohan intervenes. Subtly, he broadens the essence of Ram to include the concepts of empathy, peace, unity and progress.

He further subverts the binary of good and evil—“Ram doesn’t just reside in the devout; he also resides within the enemy,” he sings. “Look Raavan, he even resides in your heart! Whoever drives Raavan out of their hearts is capable of embodying Ram,” he claims. This song sequence is crucial for how it navigates the power of the epic tale.

In placing his views directly, Mohan knows he has antagonised the villagers. Using the poetic device of Ramleela, a musical narration of the Ramayana, Mohan hopes to get his ideas across without appearing as a culturally bereft outsider. The narrative conventions of the Ramayana thus serve as a vehicle for modern ideas of development.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

The Ramayana has inspired many evocative interpretations within the literary and cinematic traditions of India. However, the figure of Raavan has, more or less, remained a standard archetype of evil and misdoings. With the changing meanings of the anti-hero in Indian cinema, it remains to be seen whether films are capable of challenging this archetype. Films like Raavanan stoke the hope that Indian filmmakers can explore the multifaceted character of Raavan, if only they could get their ten heads to work together.

(This appeared in the print as 'Beyond the Binaries of Good and Evil')