The illusion of truth. It is in the manifesto of every propagandist’s agenda. Repeat a lie till it becomes the truth. Say it with conviction or dazzle ‘em, and they’ll never be the wiser. The propaganda minister of the Third Reich Joseph Gobbels, right wing IT cells, internet trolls, advertisers have all used it for marketing, cover-up, PR and smear campaigns. One of the most abused areas is the climate crisis. Despite extreme weather, rising greenhouse gas emissions, plastic and industrial waste, melting ice, changes in flower/plant growing patterns...the irony of 400 private planes chartering world leaders to the UN’s 2021 COP26 Climate Summit in Glasgow was lost on many.

Some know no better. Even those who do, switch off once their heating/cooling/air purifying gadgets are switched on. This is why inaccurate statements on the environment continue to be blatantly issued by those in power. To save face after international condemnation of his governance, as also his own government data showing a rise in forest fires, Brazil president Jair Bolsonaro claimed: “Tropical rainforest doesn’t catch fire. So, this story that the Amazon is burning is a lie, and we have to fight it with real numbers”. On home turf, former Goa environment minister Rajendra Arlekar in 2016 claimed, “Botanically, the coconut tree is not even a tree, because it does not have branches,” after the government passed a law in 2016, removing the need for the forest department’s permit to fell a coconut palm tree. While issuing a proposal to fell over 3,000 trees in Aarey Colony to construct a Metro car shed, former Maharashtra CM Devendra Fadnavis said: “The proposed site [Aarey] is the government’s land and it neither comes under bio-diversity nor is forest land.”

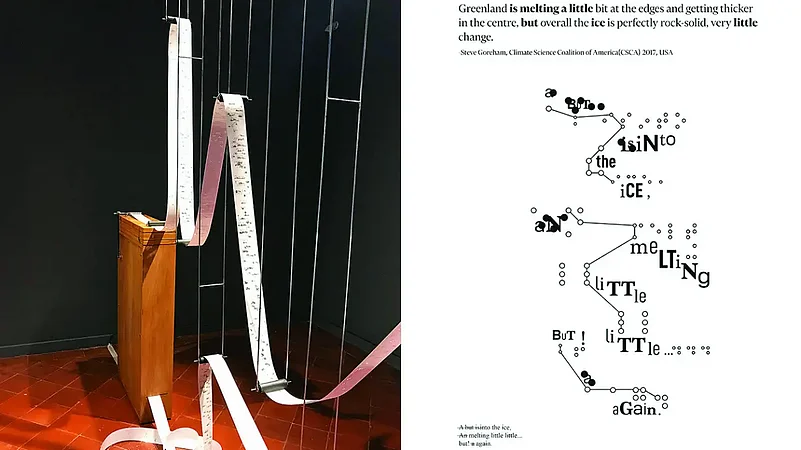

To counter such misinformation, programmer-turned-artist Nandita Kumar created a parallel universe of truth. In her 40-ft-scroll installation, titled Paradigm to Paradigm: Into the Biomic Time, names are ‘cancelled’ and truth is weaned out of 91 such spoken ‘lies’ by world leaders—which include the above three quotes. She accomplishes this by feeding the “misnomers” into a haiku code generator to omit words qualifying the lie, arrange the residual core truths into typical haiku “telegram-style” syntax with a 5/7/5 syllabic meter, and a “cutting word” for structural support. A UP minister’s tweet—“Farmers have always practiced stubble burning. It’s a natural system. Repeated criticism of it is unfortunate. Governments should hold yagna to please Lord Indra. He will set things right”— now reads: “The criticism always/with no stem/to system.”

Kumar chose the Japanese form because it is usually on nature or the seasons, and juxtaposes two opposite thoughts (e.g. natural and man-made). The regurgitated poems in her work, however, are not “the bottom-line truths… The structure of a haiku favours brevity, yet the best haikus also capture succinct detail, making them incredibly powerful in getting a message across. Poetry allows humans to cultivate deep experiences, ideas and thoughts, and empathise with difficult emotions. This experience draws them in as a collective body and unites them,” says Kumar.

The scroll carries these haikus, their Braille translations and a final stage of ‘fact-checking’, where erring alphabets or “glitches” are eliminated with punch holes. The scroll is part of a printing press setup, but unlike those loud, monstrous contraptions that convert paper reels into news pages within seconds, this is unhurried. Like a wound-up music box, it glides into a punch piano and produces a note, every time it detects a ‘glitch’, which in turn creates a notational score. Like a constant loop, the piano reiterates the ‘news’ or systemic lies in print. “Misinterpreted facts are perceived as whole truths, given that India’s demography varies in terms of literacy. But these political statements become ‘gateways’ into larger environmental issues, giving me the opportunity to collect and address these “misnomers”. Besides, I find these terrifying and amusing,” chuckles Kumar.

Most of Kumar’s works are polymorphic—one thought manifested in multiple mediums of expression. This “mini exhibition” of sorts panders to the senses in a three-part harmony. The installations appeal visually, the sound scores invite interaction and an accompanying book documents. Paradigm to Paradigm… has a newspaper press with sound score; 14 wall-mounted glass tablets of 14 haikus molded in copper; and a book collating the “misnomers” and their eco-political implications. “I use multiple ways of reiterating an idea as I believe people have a larger absorption space through their auditory and visual senses,” Kumar tells Outlook. Each medium is also multi-layered. The haikus arranged like molecular diagrams, are an ode to American composer John Cage’s mesostic poetry (in which a vertical phrase intersects several lines of horizontal text). Even the scroll—suspended mid-air, can resemble a jagged electric circuit. It can be overwhelming at first glance, but Kumar in her defense says her works “are complex, just like the political system we are constantly exposed to”. The new-media artist holds a masters degree in experimental animation in film, and was based in Goa before her selection as fellow of the 2022-23 DAAD Artist-in-Berlin programme has taken her to Germany.

Paradigm to Paradigm… takes off from her 2014 work, Emotive Sounds of the Electric Writer—a 30-ft-scroll extolling the lost art of handwritten letters. The scroll passes through an old-fashioned plotter, which mimics handwritten letters that have been entered digitally. The attached red felt pen occasionally pauses to process new information like handwriting, space and drawing, and in turn leaves ‘bloody’ ink blots; symbolic of the heavy emotions these letters would carry, leaving a score-like impression across the parchment. The score that emerges from the process is translated into sounds by musicians and composed into a sonic piece. “Just as you sometimes get the most incredible insights from human error… similarly, machine error becomes the inspiration for the sound.”

The scrolls lend a new trajectory to her regular aesthetic, of employing bio-mimicry—copying nature-inspired designs to fix human problems—to demonstrate a utopian world, where nature and technology unite to fight the climate crisis. A large part of her opus involves biospheres or dioramas, modeled after self-sustaining terrariums—another form of bio-mimicry. Terrariums only need sunlight to photo-synthesize and produce oxygen. Its other functions are recyclable, as the oxygen becomes moisture that becomes ‘rain’, and leaves that rot produce carbon dioxide, while the roots absorb the remaining nutrients.

Her dioramic Element: Earth best demonstrates bio-mimicry. “The idea was that when the sun rises, this electronic piece would start making natural sounds. If someone moves around, it would imprint another layer of sound… suggestive of human carbon imprint.” The terrarium in Polymorphic Humanscape, on the effect of urbanisation, has 24-hour-long each recordings of nature and city life, which are displayed on three tiny screens. If the terrarium doesn’t sense any movement, the screens show the recording of nature, from morning to night. On sensing movement, it starts displaying visuals of city life. It is a reflection on how important a city’s designing is, “because invariably, the city we design, also designs us.”

Much of Kumar’s imagery appears like delicate filigree metalwork mounted on acrylic slides, like specimens under a microscope. The process—of etching copper on slides—is painstaking. This is the way circuit-boards used to be printed once. Environmental data and graphs take on different forms of natural and urban life. Case in point is the installation in 126.22 Hz, based on a notational score that represents the sun and its effects on Earth. Here, jagged graphs of sunspot cycles are positioned as mountains. Fractal electronic circuits and diagrams of light perceived through the eye become roots. Atomic structure of chlorophyll becomes raindrops, phototropic graphs turn into tree branches and birds affected by solar storms take flight. And so on.

The artwork of the moment is her Osomospace: Echoes of the Osmotic Landscape, on display at the fifth Mardin Biennial that consists of a 13-ft-glass sculpture containing a graphic notational score, mural, a book and a WebApp. Kumar has collected 55 data sets and graphs on the water cycle to comprehend water-related issues like carbon infiltration, acid rain, infrastructural impact, and river and ocean pollution. For instance, one data set highlights the decreasing virility among the fish-eating men of Andhra Pradesh. Findings in this set reveal that the fish are consuming plastic waste discharged into the sea. Plastic possesses xenoestrogen—a type of xenohormone (artificially created compounds showing hormone-like properties)—that mimics the female hormone oestrogen, and reduces sperm count in men who unwittingly consume such fish. “In the long run, these men will become women, filled with oestrogen,” says Kumar. The work harks back to her earlier work, Let tHE bRAinFLy, where a character named ‘brain fly’, after much evolving, breaks away from societal dictates and enters a free, queer space.

In The Unwanted Ecology, she identifies 20 weed varieties growing in the 20-minute walking radius from her studio in Guirim, Goa. ‘Weed’ means a perennial outcast in English as well as botany, an entity to be uprooted and discarded. But Kumar harps on the relatively unknown role of these plant species’ as the chief ingredient in many a recipe, and an indigenous remedy for myriad ailments such as diarrhoea, insomnia, hepatitis, male sexual potency, etc. With global warming already making us consider alternative food practices like protein-packed insects, the oft-dismissed weeds might be in the same league. “Typical cash crops require stubble burning and copious amounts of water to grow, which the hardy, zero-maintenance weeds don’t,” says Kumar. In her electronic terrarium, each weed variety emits its own sound-healing frequency—produced by her long-time collaborator, Kari Rae Seekins from San Francisco—which reproduces resonant frequencies of organic objects. The 20 frequencies combine into a soundscape, interspersed with frequencies of insects and amphibians from the same provenance as the weeds, to demonstrate how weeds can enhance their environment.

In her quest for data transparency, Kumar leans on a network of engineers, glassmakers, biotechnologists, data scientists and science students Meanwhile, she is careful not to discriminate among data sources. It is why the thought behind many of her seminal works emerge from casual conversations with locals. After the early arrival of monsoons last year, her next-door neighbour, a kaju feni distiller, lamented how the cashew flowers were wiped out before turning into cashew apples, from which the native liquor is distilled—hitting feni production. The conversation stayed on in Kumar’s mind as she began to correlate global warming with environmentally damaging cropping practices, which led to The Unwanted Ecology.

Osomospace happened after an exchange with a Mumbai fisherman a few years ago. For an hour, she watched his unsuccessful attempts to untangle his nets. On enquiring, he pointed to an industrial outlet on the shores, discharging sewage into the “kaala paani (black water)” as he called it, with such force that a giant swirl would form, trapping his nets, fish and sewage. The exchange became a prompt, encouraging her to look at water via osmosis, as “a giant motor wave travels from my body into the landscape on to every entity”.

Kumar is vigilant of tiny ecological shifts. Like the slow fade of fireflies that, till about four years ago, would bespeckle the Goa countryside at night in huge clusters. Or, on a recent visit to Mumbai’s Bandra coastline, the observation that the area’s rock crabs have gone from red to maroonish black.

Lessons in environment conservation have trickled into her own life and art practice. Kokum pieces become scrubbers to shine copper parts of her tropical forests. Water discharged from her reverse osmosis filter is collected, rendered anti-bacterial with neem, camphor and citronella, and used to wipe floors, as it “drives mosquitoes away”. Her students at an NID workshop, learnt to build animated installations out of campus waste. “I’m making small noises to bring about change with love and patience,” says Kumar.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Righting misnomers")