Sanjay Leela Bhansali had just finished making Khamoshi. The film didn’t set the box office on fire, but praises and compliments were floating in from various quarters. Some may still consider it one of his finest films. However, during this period of rest and rumination, Bhansali got a phone call from a sexagenarian named Pratap Karvat. Mr Karvat was a writer and he had a story he felt the filmmaker must listen to. Now, Pratap Karvat is a name in the footnotes of history that keeps popping up from time to time. He finds mention in old All India Radio journals as having written a Gujarati “roopak” (dramatic composition) called Pavagadh, and hosted some shows. Mahesh Bhatt, in his book A Taste of Life: The Last Days of U.G. Krishnamurti mentions Pratap Karvat as the individual who introduced him to the great U.G Krishnamurti and his fascinating world.

Bhansali agreed to meet Karvat and listen to his narration. The plot was rather unusual. Bhansali felt he had come upon something really special. Frenzied writing sessions followed, and the final screenplay took shape. Bhansali made his own modifications but retained the core of the story. Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam was released on June 18, 1999, and was a thumping success. Salman Khan was in his prime, and Aishwarya came into her own as a mainstream heroine. At the time, some sections in the Bengali media claimed that the film had an uncanny resemblance with a Bengali novel from 1974 written by Maitreyi Devi, a writer and intellectual of some repute. Internet was still a toddler, but online forums and blogs were filled with allusions to this. The stories soon died down.

---

Calcutta, 1930

Wikipedia calls Mircea Eliade “a Romanian historian of religion, fiction writer, philosopher, and professor at the University of Chicago”. But he was also an exponent of Indology, a bona fide field of study that deals with Indian culture and philosophy. It was in vogue in the early 19th century, and scores of white men and women thronged to western universities to learn more about the mystical nation of snakes and maharajas. Mircea Eliade was one of the most prominent Indologists ever known. He wrote many books about the religious practices, philosophy and mysticism of the Orient. He also wrote more than 40 works of fiction. But in the year 1933, Mircea authored a book that stands out in his impressive bibliography. It was a novel in Romanian called Maitreyi, which was soon translated and published in French with the title La Nuit Bengali (The Nights of Bengal). It talks about a young man called Alain who travels to India on a quest to study Indian mysticism. In Calcutta, he runs into Narendra Sen, an engineer by profession but an expert on Hindu scriptures and Indian philosophy. Alain accepts Narendra as his teacher and takes up residence in his quarters. In the course of living with this hospitable Bengali family, Alain finds himself drawn to the fiery Maitreyi, Narendra’s daughter. What follows is a somewhat sexist narrative of the erotically charged advances of Maitreyi and how Alain gave in to her charms. As soon as Narendra gets wind of these amorous escapades, he promptly throws Alain out of the house, and that was the long and short of it.

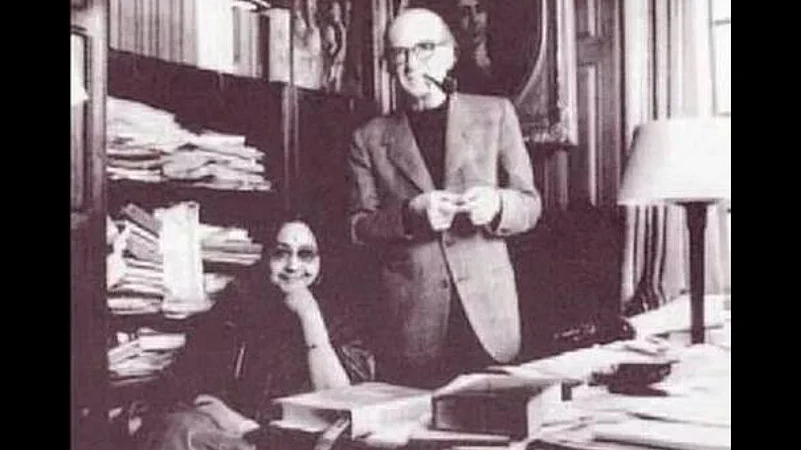

But this wasn’t just another novel. Barely three years before the book came out, Mircea had himself been in Calcutta, studying Sanskrit and Hindu philosophy under the tutelage of Surendranath Dasgupta, an authority on the subject. His “History of Indian Philosophy” in five volumes is still considered a definitive text. Surendranath was married to Himani Devi, the sister of Himanshu Rai, the founder of Bombay Talkies. They had six daughters, out of which Maitreyi, even at the age of 16, had found some success as a poet. Young that she was, Maitreyi was also respected as an intellectual in her own right. She was a protege of the bard Rabindranath Tagore. Mircea, himself all of 23, came into contact with Maitreyi Devi. Raging hormones did their thing the two young people found themselves deeply attracted to each other. A torrid romance ensued, the details of which are sketchy at best. As Dasgupta discovered this, he couldn’t stand a westerner leading his young daughter astray. Mircea had to leave. The lovers were separated and Mircea travelled through India, undergoing some spiritual and not-so-spiritual experiences that eventually shaped his worldview.

Soon after, Maitreyi was married off to Dr Manmohan Sen, an emerging Quinologist – an expert at the application of Quinine, a known drug prescribed to malaria patients. Considering Dr Sen’s rather unexciting vocation, he must have been a sharp contrast to Mircea and his intellectual fervour. But he was deeply in love with Maitreyi Devi and bestowed her with the affection she deserved and craved. In the years that followed, Maitreyi kept hearing from various sources that Mircea had dedicated a book to her. But the true extent of this was revealed to her only four decades later. In 1972, Sergiu Al-George, a friend and colleague of Mircea came visiting. Sergiu told her Mircea had written a book about her way back in ’33. He named it after her, but he depicted her as quite the seductress and nymphomaniac, the sensuous Indian beauty who tempted him. By now, Maitreyi Devi was a respected author and poet, well into her 50s. She flew into a rage at this betrayal.

In 1974, Maitreyi came up with her own response to Mircea’s version of events in the form of a novel in Bengali called Na Hanyate. In addition to spilling the beans on how it was Mircea who took a fancy to her and wooed her till she gave in, Maitreyi’s book talks about one last encounter. She confided in her husband, who then helped her travel halfway across the world looking for the jilted lover who had outraged her. She finds his university and confronts him. Mircea promises that in his lifetime, the book won’t release in English.

Interestingly, in Mircea’s book, he called her Maitreyi but changed his name to Alain. Conversely, Maitreyi calls her character Amrita, while Mircea Eiliade becomes Mircea Euclid.

Enter Hugh

This was the late 80s, and Hugh John Mungo Grant was mostly known for his outing as Maurice Hall in James Ivory’s eponymous film and a lead in the delightfully vicious The Lair of the White Worm. The rest of his work was mostly television and obscure film parts. This is when he got an offer for a script penned by the legendary Jean-Claude Carrière, an international project called La Nuit Bengali/ The Bengali Night. Mircea had passed away the same year, and it was his wife who sold the rights to the book. The film was set to be shot in Calcutta.

Maitreyi Devi, now well into her seventies, was distraught that despite Mircea keeping his word of not translating the book, a whole film was being made on their lives right in the heart of Calcutta. She fought tooth and nail to stall the proceedings, including a long-drawn battle in the court. While she failed in prohibiting the film from being completed, it was banned from being released in India. But out of respect for her wishes, the makers changed her character’s name to Gayatri. La Nuit Bengali (1988) had an illustrious cast: John Hurt, Soumitra Chattopadhyay, Shabana Azmi and Supriya Pathak. Supriya played Gayatri, and might very well be Hugh Grant’s first heroine. But the film was badly made and executed. It was released in 1988 and was quickly forgotten. Maitreyi Devi passed away a year later, in 1989. Maine Pyar Kiya had just been released, and Salman Khan was the shining new star of Hindi cinema. In 10 years, he was to be part of a film that shared some similarities with a long-forgotten love story, where two lovers fought through the books they wrote.

(Those interested in the Maitreyi-Mircea story should turn to this heartfelt piece by Ginu Kamani on the University of Chicago’s website. I have borrowed generously from there.)