This scene was never shot, but does that matter? It matches a diagram in your head—in our collective head. We recognise all the elements in this romantic impasto. We’ve seen that paper moon a gazillion times, attained a state of bionic senility. Point a cursor and click on the diagram, and a medley of sounds too picks up from some corner of the brain. They strangely match our phantom set-piece—so flavoursome despite its bare economy. We could even swear we know the lyrics—give me a minute, it’s at the tip of my tongue.Even a false cue automatically opens up a folder—the Fifties, C:\MyMusic\ Bollywood\50s. Vast mountains of para-real, audio-visual stock are stored up in each of us, permanently burned onto our memory cells. Whether the point of reference for your kind of film music is C.H. Atma or Trickbaby—or anything else from the half-a-century of pauseless music-making that intervened—you’ll have your Top 10 and Top 100, neatly catalogued. The rest is mnemonic debris, sheer inorganic waste floating in mindspace. It lies dormant till that accursed song floats up from the transistor on the migrant labourer’s shoulder, the family playing antakshari in the park...Hai Hukku Hai Hukku Hai Hai!

Call it passion or pathology, the film song is so basic to our landscape—like neem, or pepper, or cows on the roads—that we’re liable to not notice that it’s a special kind of artefact. Uniquely Indian, found in all its climatic zones, warm-blooded but immune to the snow. A supremely adaptive beast, it has segued well across time too: we have online antaksharis, Pallo Latke ringtones available for download, and a certain search engine called Yahoo! The film song is part of our suspended particulate matter. It’s in the air. At the water park. At the barbershop, on the ghettoblasters, all over TV. It’s the chewing gum that never leaves us.

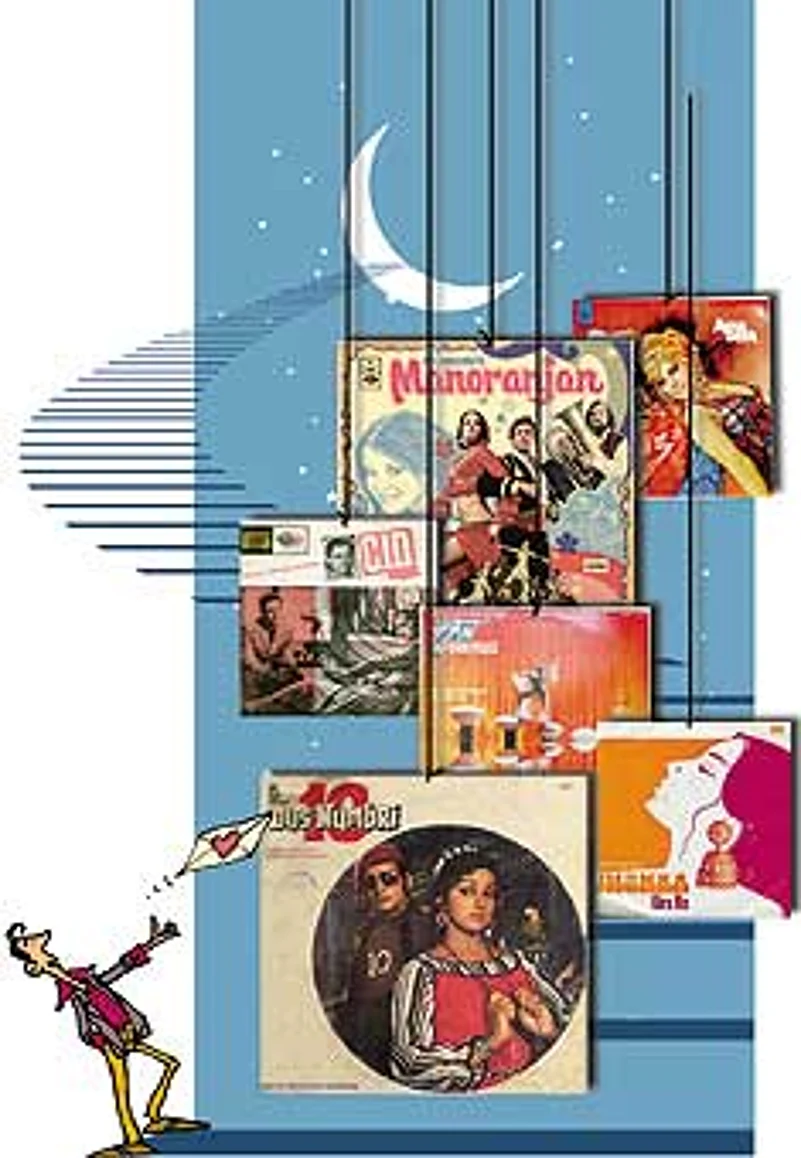

We know all its visual cliches. The party dude at the grand piano, city girls cycling to a picnic, the Shakin’ Stevens in his open-top convertible, urchins, fakirs, sundry nobodies. We also parse it by its logical type. Like the declarative song that sets up a character—‘I am...’, and fill up the blanks (Awara, Jhumroo, Dus Numbri, Don, Aflatoon, Chameli, or whoever) All this trivia serves no tangible aesthetic function. It’s a shared database of no use except that it is shared—a zone of overlap in the experience of millions who will never know each other. It makes us all participants in a common pop history, with or without our consent. The old puritanical avoidance of films for its ‘low culture’, or the cultivated dislike of the convent-bred, they’re no immunity against the ocean washing up on your front porch. There are no draft dodgers here.

So much power. By what decree did it colonise the whole landscape of sound? That too in a country of a million songs of the earth, such richness of rhythm and tone? At its root, for a people who had lost patience for all that is archaic, it came as a technology that produces newness. This function is constant in each of its time-zones; only the aspect changes. It occupies a new habitat, a temperate flatland that shuns anything too ‘arty’, anything that bears the vestiges of ‘vulgar’ folk culture. Not abstaining, but coopting—it extends its body to ingest anything it fancies. It freely ransacks from the classical and folk libraries, and then burns down the building. The formula has incredible normative power. Its values seep into all genres. It creates a taste, a vast middle continent of sensibility. Anything as pervasive as this changes the whole ecology. India is seduced into believing this is the natural way to be.

Far from being an autonomous form of music, the film song is a complex genre that tapped into vital psycho-social needs of a newly independent people. The primary desire was this: to be modern. The second was a troubled negotiation with sexuality. These were articulated and satisfied at both the aural and visual levels. There was a good reason why the alcohol-soaked voice of Saigal—a throwback to dissolute feudal times—and the thumri-style voice of the likes of Zohrabai Ambalewali disappeared and a ‘clean’ voice took over. A new breed of singers emerged to provide the soundtrack to a nation in infancy. In voice and diction, they were urban, pasteurised, decidedly free of the residues of caste and province, and offered the vision of a new moral centre. Novel, yet reassuringly noble. Thus was instituted a tyranny of the ‘good’: a stable, fluxless median; a studio where Ustad Faiyaz Khan would have surely failed the audition test.

One reason why it exercised such a hold on the collective imagination is the warm, sexual aura that emanated from the screen. It’s not now that songs have begun to look like music videos. Image was part of the complex from the beginning—for years, we were glued to a weekly dose of songs: Chitrahaar, literally, a string of images. The film song is the song video non pareil—an imaginal realisation of modernity, a magnified visual field on which sexual desire is projected and sublimated in tightly ordered metaphors. Remember all those open declarations of affection in public parks. The hero in white drainpipes, the lady in increasing aspects of coquetry, gambolling around fountains and neat rows of flowers. The park is a critical locale: as nature, it beckons our sexuality, but it is an organised, controlled piece of nature. Only so much amour can be tolerated, only intimations of the erotic. The romantic duet of film is pure surrogate sex. Those tulip fields offer fragrant violations of the moral code. No more. (Songs in the forest, on the other hand, are a descent into the carnal: pre-marital coitus, ‘tribal’ dancers in hula skirts, pure body.)

At the level of voice, the tensions were played out in a dual prototype neatly encapsulated by the Mangeshkar sisters: Lata—pristine, virginal, chaste—and Asha, all salted peanuts, the mistress of spices. On screen, this progressive barter with sexuality was catalysed by the advent of colour. The silvery, silhouetted waifs of the b&w era were filled out to become fleshly apparitions. Dheela dheela kurta, pajama tang tang. You were invited to consume the very pinkness of their health—a potent, ravishing vision of what everyone wanted to look like. For a fast modernising gentry, this was the avant garde. All this worked even in regional cinema. The singing romantic pair as marionettes in our inner puppet play, mannequins on which attire changed mid-song, like on the ramp. As ideals of the masculine and feminine, with a neutral accent, effacing all the pettiness of our horizons—a sociological newborn, a tabula rasa on which you painted the fall collection in lurid colours. ‘Golden voices’ were the aural complement—with a superficial euphony, they created cultured, yet modern entities. An endlessly renovating creation myth.

The music itself is the pivot. The way the film song ‘cleared’ the forest for its own cultivation, how it set itself up as a dandified version of its country cousins, is not without precedent. One only needs to go back to Tagore. At one respectful remove from a variety of musical forms in that continuum between folk and classical—tappa, Brahmo devotionals, Baul and the like—and a nodding acquaintance with Scottish border ballads, he spun a new, light signature imprint. As a freely borrowing organism who created a speci-fic kind of modern space out of traditional raw material and western inputs, Tagore is the godfather, all modern film composers his spiritual heirs.

But the film song had a more complex mandate. There is wide consensus on seeing the two-decade period around the ’50s as the golden age, a period of efflorescence when composers defined the genre and gave us its enduring classics. But they also set the limits from which it never liberated itself. The insistence on a ‘light’ music; the structured brevity of the film song; its very conception as a discrete packet of sung lyric for which the film soon became a mere excuse—with due apologies to the masters, they overdefined the cinematic function of music and sowed the seeds of its decline.

More crucial is how they positioned the genre, cannibalising from folk and classical and yet keeping a disdainful equidis-tance from both. The classical musician as a butt of ridicule, as someone inherently comical, is a favourite trope. Naushad facilitated one of the few pure classical moments in film by drafting in Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan to do the Tansen voice in Mughal-e-Azam. The result—Prem Jogan Ban Ke—sometimes doesn’t even get listed among the film’s songs. Perhaps rightly, for the khayal’s dark, erotic undertow becomes pure atmosphere. The Salim-Anarkali rendezvous by night on low flame. But Naushad could also splice his Madhuban Mein Radhika—Rafi on Dilip Kumar—with a comic interlude of superfast taans filmed on that vaudeville clown, Mukri. Rafi couldn’t have done that in a hundred takes; the uncredited singer is one S.D. Batish.

In film after film, occasional flashes of traditional voice cultures are allowed, only to put the ‘clean’, modern voice in favourable relief. Even classical music-based films in the South routinely see authentic performers lose out to the likes of K.J. Yesudas. Not even Ray was above this. In Goopy Gyne, the untrained Anoop Ghoshal trumps over a durbar full of ustads. Goopy is a country bumpkin, his voice is decidedly cosmopolitan. The tacit, subliminal effect is the same: a belittling of the old, a coronation of the new. Classical musicians, in their chequered film careers, have struggled in vain. The Amir Khan-Paluskar duet in Baiju Bawra, a stray Kishori Amonkar—they’re too bound up in the filmi genre to offer an alternative. The Shiv-Hari duo in the ’80s are indistinguishable from middle-of-the-road tunesmiths. The genre does not rise up to meet them, they have to stoop to be accommodated.

Why did a fuller exploration of the filmic potential of music not happen? One, a weak conception of background scores, even sound in general. You recall the welding machines and the prison guard’s hair-raising sab theek hai in Bandini; the ominous, creaking swing as motif in Sholay, maybe a few more. For the rest, the same stock music of screeching violins sufficed for a half-century. We never got to the stage of imagining a pure ambient, aural element melding into the texture of film: it perhaps needed a less denotative cinema. Our films—legatees of a variety of oral genres, from epics to theatre, replete with song if not entirely in sung verse—came to prioritise the logic of narrative over pure image. Regardless of its growing tenuous relation to plot, the song retained its subservience to this scheme: the words are important. Classical—abstract, non-representational, music for its own sake—tends to reduce its lyrics to mere syllabic matter, its melodic, percussive elements. It is the antithesis of narrative. This is the unlit intersection at which film and music lost each other.

There’s another rupture. The film song is the first Indian musical product to start its life not ‘live’ but in the studio, under controlled norms of production. This has definite implications on how people consume and reproduce it. In traditional forms, no performance is the same as the previous edition—they are born of spontaneity, of the moment. This imaginative reconstruction marks their very life and evolution. In contrast, film songs are a dead canon. You are sworn to reproduce exact replicas ad infinitum. It does not stimulate you, you simulate it. Give most people a set of favourite ‘numbers’, and they will uncomplainingly go through life—playing, rewinding, replaying.

The ‘art’ film offered a counterpoint to the pageantry, mostly by reacting in excess to the excess. It preferred a pared-down soundscape, large black pauses populated only by the screeching of crickets. However, it didn’t begin with such austerity. You had Ray, making his own cinematically motivated music—simple, tight sonic lines to go with his precise, controlled frames. He knew the uses of music, but was an authoritarian master, unwilling to let it be a law unto itself or give it a chance to run away with the plot. You had Ghatak, brimming over with disembodied song in sheer joie de vivre and pathos. Titas Ekti Nadir Naam is yet to be matched as an alternate vision of a musical opus. A stray Aravindan uses Chaurasia. A Mani Kaul—who knows a thing or two about music—writes some eerie caterwauling for Idiot, but given that his real skill lay in ensuring that nobody saw his films, it goes unheard. Then it largely peters out into a brahminical disdain of song.

So we’re stuck with this curious beast, the mainstream film song. The serenade, the tease, the mating dance. But is that all that bad? We often associate with music for reasons outside music—a cultural aura that appeals to us, whether it’s Tyagaraja, Deep South blues, Sufiana, punk, or Benarasi thumri. Why not this mass idiom—after all, it had its moments: the ghostliness of Mahal; S.D.-Sahir-Guru Dutt and their poetry of the gutters; the madcap revelry of the Ganguly trio in Chalti Ka Naam Gaadi; the extended kotha sessions of Kala Paani; C. Ramachandra and Bhagwan Dada, the original Cha Cha Chaudhari. Panjak Mullick for grandpa, Panchamda for the babyboomer, Bure Bure for the bobbysoxer. In one sense, the film song is not a genre but a basket of genres. No one expects a billion people to walk around in a state of permanent exaltation—Bhairav at dawn, raatri bela Bartok! Life is full of fallen moments—the shameful, the salacious, the cheap—and they will find expression outside classical notions of beauty. We have the sublime precisely because our emotional repertoire contains its binary opposite. The sheer lunacy of the film song satisfies this need for the ridiculous.

This potted history excluded prehistory—the silent-era live musicians playing to the flickering images on screen—and also the contemporary. Let’s recap: A formative, exploratory stage, ’30s-40s. A ‘golden age’ when the genre comes into its own. A static period: it degenerates into a stock of cliche but still delivers the goods. The decline: the muse all but deserts the scene. And a post-TV period. Ironically, just as the limits on filmic imagination were set in the best period, our liberation from them may have happened in the stalest of them. In retrospect, the ’80s may have done some good. Film music got so bad that non-film forms finally got the space to breathe. A brief ghazal age seeped in from Pakistan—and then qawwali, in the eye-catching shape of Nusrat. In Tamil, Ilayaraja cracked the harmonic basis of western music—Hindi had till then only copied melody; violin, sitar and the final flourish on the flute always followed each other between mukhda and antara. A.R. Rahman brought this new strain up north, all booming bass and folk airs. MTV was not just a channel, every channel was MTV. And classical actually saw an industry renascence of sorts, catering to a new audience—less literate, but eager to consume.

And something is afoot in the new song video-style numbers. Their disengagement from plot is complete—they often come when the titles roll up. And the voices. What was begun in the street-smart ’70s—Kishore, the commonplace, inner-city voice gaining over the crystalware—has come to fruition in a full-blown explosion of street patois. All the old idioms and registers we kept out of the frame, the voice cultures of folk minstrelsy, are filtering back in. Almost as if we see now that a vacuum had infiltrated that first folio of the modern: we want a reinfusion of raw lifeblood. Our new singers are all real or simulated versions of the qawwal, the dervish, the mirasi, the bhangramuffin, the bhaiyya—a tentative nod at a fuller range of Indian tonality. They’re all bounding about in a bawdy, energetic, hybrid electro-folk thrum. They even want to be the ones to get the girl. Heard the latest? Mika ko ishq brandy chad gayi...