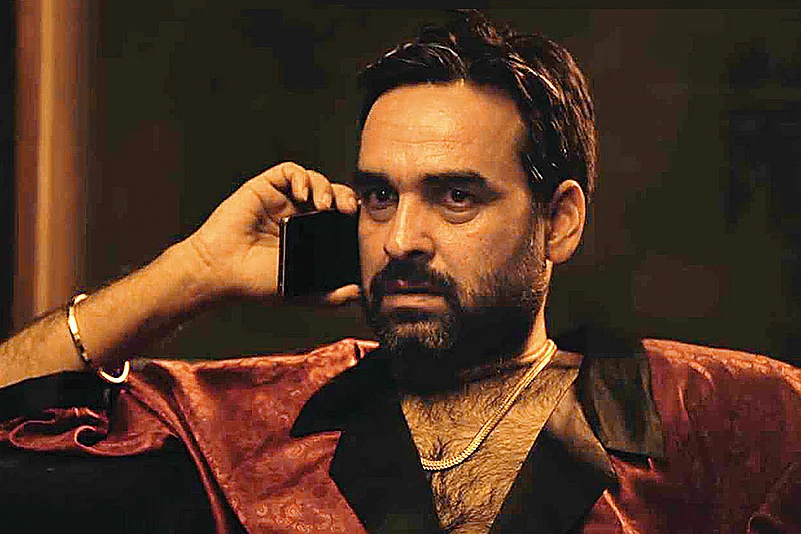

Like any star in the ascendant, his cellphone has not ceased ringing ever since Newton opened to rave reviews last fortnight. His realistic portrayal of Aatma Singh, a cynical paramilitary official saddled with the responsibility of ensuring peaceful polling in the middle of a Naxal-infested forest, has elicited unstinting accolades from within and outside Bollywood. The producers are already queuing up to snap up the actor whose versatility has finally made the otherwise squeamish film industry sit up and take note.

Apart from establishing Rajkummar Rao as a formidable A-lister within the alt-mainstream cinema space, Newton marks the arrival of Pankaj Tripathi, the Bihar-born actor who is being hailed as a powerhouse of talent by critics after an array of impressive roles in recent movies such as Bareilly ki Barfi, Anaarkali of Aarah, Gurgaon and, of course, Newton. The latter, a black comedy on the country’s electoral system, has incidentally been picked up as India’s official entry to the Oscars this year. In addition to receiving critical appreciation, the film has been doing excellent business at the box office, which picked up due to a positive word-of-mouth in its second week notwithstanding the release of a big mainstream movie like Judwaa 2.

“I had realised during the shooting Newton that the audience would appreciate this film and my role in it,” Tripathi tells Outlook. “In my opinion, if a character turns out to be listless and one-dimensional on screen, he cannot sustain the audiences’ interest. Thankfully, Newton’s Aatma Singh is made of varied shades. ”

As Kehri Singh, the real baron, in Gurgaon

The original script had the character painted in black, reveals the 42-year-old actor. But he was able to convince the director (Amit Masurkar) to add more shades to it. “I told him that Aatma Singh is part of the system and, therefore, it would not be kosher to project him as an outright villain and he agreed to make the changes.”

What came in handy for Tripathi for the role were his own experiences in his native place Belsand in Bihar’s Gopalganj district where he spent his formative years. “Raghuvir Yadav and I were the only actors in the unit who had the first-hand experience of watching elections in a remote village,” he says. “I have been a witness to how booths would be looted and ink poured into the ballot boxes to rig the polls in my village. As a matter of fact, I was once made to cast a bogus vote when I was barely 10 or 11 years old.”

The familiarity with the once-violent electoral process in his home state, when polling stations were looted by gun-toting marauders with impunity, helped him add nuance to his character. “Others, mostly youngsters, in the unit knew about the phenomenon of booth capturing only through books and old newspaper files, but I had seen everything from close quarters. I still remember how my village got divided invariably on caste and religion lines on the eve of each and every election in those days.”

as Aatma Singh in Newton which released last month

Belsand remains devoid of basic amenities even today. “My village is still not connected with concrete roads. It’s where I studied under a tree till class V,” he says. “But I do not intend to talk about my humble background merely to garner sympathy. I think my early life, bereft of adequate resources, has been my inherent strength. I have always believed that no sapling will ever spring to life unless its seed remains under soil for some time.”

And Tripathi has banked heavily on this ‘strength’ in his career so far. “In Anaarkali of Aarah (2017), when an offer to portray a man who runs an orchestra featuring raunchy dancers came my way, memories of all those nights when I used to slink out of my house—and often got beaten up by my father for watching such shows in and around my village—came to my mind in a flashback. I knew the INS and outs of such orchestras that operated in the interiors of Bihar and drawing on those experiences, tried to inject realism into my character,” he says. “Similarly, in Nil Battey Sannata (2016), where I played a government school principal, director Ashwini Iyer-Tiwari left it entirely to me to develop the character since I had also studied at a government school.”

It was that character, suffused with subtle nuances and inimitable mannerisms, which convinced Ashwini to offer Tripathi the role of the father of lead actress Kriti Sanon in her next venture, Bareilly ki Barfi. “It was not exactly the right age to accept the role of father. I have just turned 42, but I took it up as a challenge,” he says.

He did not have to regret his decision, as he ended up getting plaudits after the film turned out to be a hit earlier this year. “In Bareilly ki Barfi, I did not play the stereotyped father,” he says. “He shared a close bond with his daughter and did not even hesitate to ask her for a cigarette. Such a father-daughter bonding had never been seen before.”

The hep dad from Bareilly Ki Barfi

His versatility, to switch over from one role to another with consummate ease and conviction, has turned out to be his USP. “Pankaj can fit in any role. He is like a chameleon,” says Ashwini, who has directed him in two of her acclaimed movies. “Actors like him should be preserved,” she adds.

Tripathi believes that actors like him, who come from a humble background and struggle for many years before getting recognition in the industry, have a wealth of experience to draw from. “Interacting with people while travelling from a village in a crowded bus, listening to their remarks laced with earthy wit and humour, all provide an insight into a life not found in big cities,” he says.

It was in his village that he was first drawn towards theatre in his younger days. “Since nobody in my village was willing to play a female character in the drama held every year during the Chhath festival, I volunteered,” he says. “But the organisers always advised me to seek prior permission of my father, which wasn’t a problem.”

with Swara Bhaskar in Anaarkali Of Aarah

His father, a priest and small-time farmer, wanted to see him as a doctor. So after Tripathi passed class X, he was promptly sent to Patna for medical coaching. “I enrolled at a coaching centre but had no interest whatsoever in studies. Instead, I was drawn towards student politics and joined the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad,” he says. “In 1993 when Laloo Prasad was the chief minister, I actually had to spend seven days in Beur jail in Patna for protesting against a police firing on students in Madhubani district.”

However, it was not long before Tripathi got disillusioned with politics and took to theatre in a big way. “I had realised by then that there was no place for honest workers in politics,” he says. “No leader liked criticism of any kind. They only wanted spineless followers around them to sing them paeans. So I started spending more and more time at Kalidas Rangalaya, the theatre hub of Patna, watching plays, interacting with actors, playwrights and litterateurs. I also read the books of the best of writers, from Maxim Gorky to Phanishwarnath Renu in those days. ”

The 1990s saw Tripathi plunging headlong into theatre. He acted in and directed hundreds of plays before making it to New Delhi’s National School of Drama in 2001. “After graduating from NSD, I did go back to Patna but I knew it was not possible to do theatre without being obsequious to the ministers and bureaucrats for government aids and grants. So I decided to move to Mumbai in 2004.”

But it was not easy for Tripathi in tinsel town. He spent the next seven-eight years, doing bit roles in eminently forgettable television serials and movies. The turning point, he says, was a role in Anurag Kashyap’s Gangs of Wasseypur (2012). “I have done the longest audition of my life for Wasseypur. It took eight hours to enact all the scenes for Sultan Qureshi, my character in the film. Anurag saw the audition and liked it.”

The release of the film brought him into limelight for the very first time in Bollywood. “Critics began inquiring about me but I did not know how to cash in on the film’s success. I still don’t have any marketing skills,” he says. But things have already started changing after his recent films, admits Tripathi. “I have never met Mahesh Bhatt in my life, but he called up the other day after seeing Newton and told me that he wanted to hug me for my performance,” he gushes. “He told me that he hadn’t seen such an honest performance by any actor for many years and that I was flawless in each and every frame. Coming from a venerated film-maker like him, it was indeed a huge compliment for me.”

Tripathi is now looking forward to Fukrey 2, which will be released in December. “I am hopeful that my performance in Fukrey 2 will surprise people,” he says. As of now, he is working in Kaala, a big budgeted Tamil movie starring mega star Rajnikanth. “I am doing Kaala only to see Rajnikanth, the phenomenon. I wanted to understand how an actor can be as popular as him.”

Tripathi confesses that the rush of accolades for his recent films has overlooked one performance close to the actor’s heart—that of real estate builder Kehri Singh in the film Gurgaon (2017). “I regret that many people did not watch Gurgaon, where I played one of my toughest roles,” he says with a sigh. “It did not get enough screens since it clashed with a big movie at the box office. But I am sure many people will see and appreciate it on the digital platforms such as Netflix and Amazon Prime.”

From the dusty lanes of his village to the glitz and glamour of B-town, via the dingy cell of a jail, Tripathi has come a long way. Despite tasting success, he wants to keep doing all his roles with equal honesty and prefers to let his work do all the talking for him even though, he says, such honesty is often not appreciated on the editing table. “At times, some bigwigs don’t like such honesty in my performance and get my roles pruned arbitrarily,” he says.

But that is not something unheard-of in a star-driven industry where good actors like him have always paid the price for being who they are.