This article was published in the Outlook magazine issue 'Emergency: The Legacy/The Lunacy' dated October 1, 2024. To read more article from the issue, click here.

Like flies hovering over a mithai in a sweetshop, Bollywood filmmakers keep gravitating to an old trend that never gets old: biopics. At least five such movies have hit the theatres this year, with the most awaited one, Emergency, yet to find a release date. This sub-genre has thrived for so long that even the reported pieces on it sound stale. Commenting on the trend in 2015 and 2024, The Quint and Deccan Chronicle published identical headlines (“It’s Raining Biopics in Bollywood”). With over 40 of them releasing in the last decade—many finding novel ways to be mediocre, swinging from brain-dead to propagandist—this formula continues to flourish.

This surge in interest seems remarkable, as biopics didn’t interest Bollywood filmmakers for decades. They had remained so indifferent to real stories that it took a foreign director—and production house—to make a movie on a revered Indian, Gandhi (1982). It makes sense. For an industry fixated on sweeping spectacles—soaked in songs, escapism, and melodrama—Bollywood revels in not depicting, but contradicting, realism.

So art-house filmmakers sought to harness the biopics’ potential. Shyam Benegal made Bhumika (1977), exploring the life of Marathi actor Hansa Wadkar, and later, Zubeidaa (2001). Ketan Mehta’s Sardar (1993) won two National Awards. And when a commercial director, Shekhar Kapur, helmed Bandit Queen (1994), he chose stark realism—theatre actors, no songs, shocking violence—positioning it as a ‘serious movie’. Some filmmakers gave a new spin to the format by making mainstream, yet ‘reflexive’, dramas, such as Guru Dutt (Kaagaz Ke Phool) and Raj Kapoor (Mera Naam Joker).

By the early aughts, this trend had still not exploded, though in 2002, three movies on Bhagat Singh released in a span of few weeks. This sub-genre was so dormant, in fact, that a rare Aamir Khan misfire in that decade, Mangal Pandey (2005), was a biopic. But in the subsequent years, The Dirty Picture (2010), Paan Singh Tomar (2012), and Shahid (2012) foregrounded forgotten (and ‘infamous’) individuals, telling stories of dwindling dignities, quiet fights, desperate determinations.

And then, Bhaag Milkha Bhaag (2013) changed it all. It was a box-office smash, becoming the fifth-highest grossing film of the year. Even though it got positive reviews, it was factually dubious and tediously jingoistic, injecting drama in an already dramatic story and making a hero more heroic—a trait about to become a trend.

The initial explosion of the sub-genre produced sports biopics, such as Mary Kom (2014), Azhar (2016), and MS Dhoni (2016). They didn’t examine—but extol— the individual, celebrating the celebrities. Even a movie with a controversial protagonist, Azhar, contrived a ludicrous reason to justify his match fixing. As the biopics took different forms in the 2010s, that problem persisted and amplified. A film on Sanjay Dutt, Sanju (2018), made by his friend Rajkumar Hirani, sanitised the star’s life so much that it felt like an apologia. The movies on Dhoni and Nambi Narayanan (Rocketry) unfolded like Wikipedia entries. They had narratives but no plots—or bite and insight. And like many Bollywood biopics, they failed to differentiate between truths and facts.

“What really matters is whether you were able to extract the rasa [the essence of the story],” says Ram Madhvani, Neerja’s director. “Was it actually meant to be inspiring—or inspire courage? Because we’re not in the business of a plot or a story. We’re in the business of feelings.” The Bollywood biopics—especially those centred on sports stars—reverse engineer that approach. They seem to start from an MBA-like bottom-line, an ‘inspirational’ story, and then spin a screenplay around it. Inspirational, then, isn’t their organic outcomes but pre-ordained destinies, drowning out curiosities, complexities, and discoveries.

Mediocre biopics reduce a complex life into a hard thesis. Picking out one pivotal strand in their subjects’ lives the directors hammer that point again and again, contriving causality and mocking realism.

The “anecdotal” style, says Hansal Mehta, also hurts many biopics. A typical research for such a project results in a filmmaker meeting the subject’s associates who relay stories. “But instead of [writing] a screenplay or developing the character, the makers rely on anecdotes, and that anecdotal nature takes away the cinema from most biopics. People try to force-fit them—the anecdotes become the subject.” Or, in such movies, the vignettes of a life become life itself.

Mediocre biopics also reduce a complex life into a hard thesis. Picking out one pivotal strand in their subjects’ lives —the trauma of Partition (Bhaag Milkha Bhaag), a mathematician struggling to be a mother (Shakuntala Devi), a misfit repulsed by tradition (Pad Man)—the directors hammer that point again and again, contriving causality and mocking realism. In Bhaag Milkha Bhaag, it’s not enough that the Partition has ravaged Milkha Singh’s childhood; it also must haunt him to the extent that he turns back during his 1960 Olympic sprint, making him lose the medal. (Of course, it never happened.) Bollywood filmmakers’ strained relationship with realism exposes a fundamental flaw in their mindsets: that, yes, real life is interesting—but only till a point. Excellent biopics take dramatic liberties to scale higher truths, but simplistic ones twist facts to serve the stars and the subjects.

So they’ve become formulaic and a formula. You know the beats (the background, the obstacles, the triumph); you know the tropes (a training montage, a rousing song, a convenient villain); you know the effects (patriotic, inspirational, admirable). You can switch the sub-genres and still get the same result. Bollywood directors also become “overly fascinated with their subjects”, says Mehta, reducing biopics to a mutual “pat on the back” exercise. In fact, just look at what passes off as ‘entertainment journalism’ in the country—a senior journalist or an influencer (is there a difference anymore?) lobbing easy questions to stars, helping them promote their films or brands. Bollywood biopics do that over two hours—with some songs and a love story. They’ve sprung from this exact ‘celebritification’ of our culture, where we’ve become too dazzled by the stars to even question them.

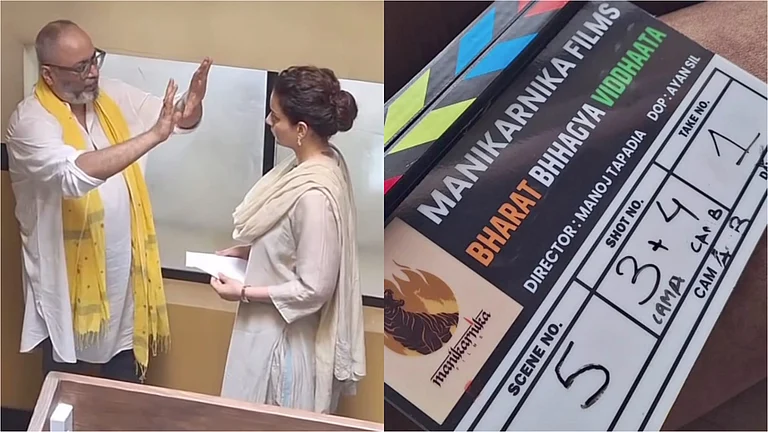

“Many filmmakers also want their protagonists to look exactly like the real-life characters,” says Mehta. “That’s another place where we go wrong. We give people wild prosthetics; we make them mimic accents.” Kangana Ranaut drew attention to her looks in Emergency—underscoring the Oscar-winning credentials of her makeup artist, David Malinowski, and releasing multiple photos of her transformation—on social media. “If you’re showing Gandhi on screen,” says Mehta who, adapting Ramachandra Guha’s books, is making a three-part series on the freedom fighter, “then it doesn’t mean his ears need to pop out. It’s not about the physical Gandhi, but what he stood for.”

For all their flaws, though, Bollywood filmmakers do face several obstacles while making biopics. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Samajwadi Party (SP), for instance, wanted to ban Mangal Pandey because it showed the soldier visiting a sex worker’s house. Silk Smitha’s brother sent a legal notice to the makers of The Dirty Picture for showing her in an “obscene” light. The Indian Air Force (IAF) wrote to the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) after Gunjan Saxena’s release, saying the film portrayed the IAF in “undue negative light”. (Taking offence in India is like falling in love—it can happen anywhere, anytime.) And these are, of course, a small sample of controversies related to recent biopics.

Unlike the US, which protects filmmakers through the First Amendment, the Indian censor board throws them to the wolves by asking them to furnish an NOC from the biopic’s subject or their kin.

Unlike the United States, which protects filmmakers through the First Amendment, the Indian censor board throws them to the wolves by asking them to furnish a No Objection Certificate (NOC) from the biopic’s subject or their kin. The CBFC chief, Pahlaj Nihalani, asked the makers of The Accidental Prime Minister (2019) to get NOCs from former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and Sonia Gandhi. The directors of An Insignificant Man, who made a documentary on the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), had to procure NOCs from Narendra Modi, Arvind Kejriwal, and Sheila Dixit. For Shahid, Mehta had to take an NOC from the wife of the deceased lawyer Shahid Azmi.

But a new challenge has sprung up of late: “legal due diligence”. Mehta experiences it often, and each time he discovers something new. “In Scam 1992, we had shown the logos of all the real organisations. But after the edit, the legal teams said you can’t put logos. So we spent about a month and a lot of money removing them.” There are other restrictions, too. “You can’t name politicians—even if it’s researched or in the public domain—because they’re the first ones to cause trouble. You can’t name certain business houses.” The legal teams, he adds, have now become part of the writing process. “There’s an entire book waiting to be written on how filmmakers circumvent these challenges.” These days, even before writing the screenplay, he says, it goes to a legal team. “And then that whole document comes—the risk of legal exposure—and you take a look at it and say, ‘Okay, do I really want to make this?’”

The risk of lawsuits—or censorship—doesn’t apply to all directors though. Consider another movie made on the Emergency, Indu Sarkar (2017), which, unlike The Accidental Prime Minister, didn’t have to provide an NOC to the CBFC. If Bhaag Milkha Bhaag was one inflection point in the narrative of Bollywood biopics, then Indu Sarkar was another. It produced a two-pronged strategy: using a real-life story to manufacture heroes (right-wing leaders) and villains (the Congress party, activists, journalists—it’s a long list). Such movies didn’t court controversies because the ruling party considered those heroes and villains as...heroes and villains.

A few years later, Bollywood biopics started to valourise controversial figures known for their dictatorial streaks or jaundiced views (or both): Thackeray (2019), Thalaivi (2021), Swatantrya Veer Savarkar (2024), and more. A few years ago, Mahesh Manjrekar announced a film on Nathuram Godse and, in 2018, news surfaced that that S S Rajamouli’s father, K V Vijayendra Prasad—who has scripted Bajrangi Bhaijaan (2015), Baahubali (2015), and RRR (2022)—was writing a drama on the origins and story of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS).

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

In most filmmaking cultures, Emergency would have been an anomaly. But in the Bollywood of 2024, it looks inevitable. Its trailer indicates that Ranaut, the director, has taken the two-pronged approach a step further. The movie vilifies Indira Gandhi and admires Atal Bihari Vajpaaye (as expected), but it also targets another enemy, the Sikhs, who are depicted as violent separatists. Their complaints, though, compelled the CBFC to rescind its approval, halt the release, impose 11 cuts, and eventually grant a U/A certificate. Ranaut hasn’t announced the new release date yet, but that doesn’t look too far away, and if this film becomes a hit, then it’d accelerate the (vicious) biopics even further. It’d also complete their true journey: from telling the stories of making the nation to breaking the nation.