“I wanted to make the invisibles visible,” says filmmaker Anubhav Sinha on his reasons for taking on the subject of migrant workers and giving it life on celluloid. His recently released film Bheed (crowd) is a social drama set during the events of the 2020 COVID-19 lockdowns in India. The film, an account of the largest migration in India—since Partition—from various parts of the country towards Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand and West Bengal, has got rave reviews, especially for the performance of lead actor Rajkumar Rao. Sinha, originally from Jamalpur, Bihar, moved to Mumbai in 1990 to pursue filmmaking, and can now boast of an impressive filmography. His movies such as Article 15, Mulk, and Thappad have received critical acclaim for deftly tackling subjects like caste, communalism and patriarchy.

Edited excerpts from an interview with Haima Deshpande in Mumbai.

Could you elaborate on any personal experiences that pushed you to make a film like Bheed?

I think I was moved by the general apathy towards the situation and the people involved. The very people who make our lives run in the bigger cities are apparently invisible. We think of them when they don’t come to work. The day when the domestic worker doesn’t come is the day we think of her. The rest of the time, we don’t bother about her; we take her for granted.

This was true for me as well at the time. The COVID-19 lockdown was the time when they became starkly visible to me.

I remember when the lockdown was announced, for days I was cooking from home and posting pictures on Instagram until I realised how insensitive that was. They (migrant workers) were trying to find bread for their children. I felt disgusted. That’s when I quit all of it and started this whole journey of helping people—like the watchman in my building— and contributing to people who were cooking and distributing food.

I started finding more and more friends who could contribute. When that journey began, I got exposed to greater misery, more apathy but empathy as well. I think somewhere along, the idea of this film germinated.

Is this film based on media reports? What are the other sources that went into it?

There was a lot of research. I spoke to a number of people, some journalist friends who were on the ground at the time. I read a lot of media reports and saw a lot of interviews of migrant workers who were walking back. A lot has gone into the making of this film.

In terms of production, how long did it take to make the film?

I think I must have conceived of the idea during the first lockdown. The writing process took about a year and a half. We shot the film in December 2021 and released it in March 2023.

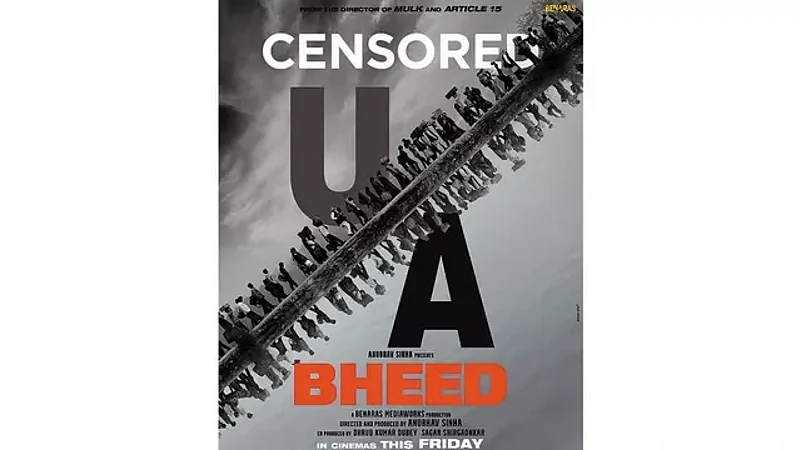

This film seems to have faced a few issues with the Censor Board. Did you have to make any changes to the film based on the Board’s directives?

Yes, I did have to make some changes. That is a filmmaker’s battle and I don’t want people to be privy to it. I make films for people to watch and enjoy. If there is something I have to stand up to I would but I do not want to hamper their viewing experience with issues that do not concern them at all.

You are also from outside Maharashtra and made Mumbai your home. Would you say the pandemic-driven exodus of people —the largest since Partition—touched a chord somewhere in you?

In hindsight, subliminally, it must have. When you come to a bigger city you don’t know enough people, you know you are by yourself. Then you find your ground, you go up, you learn to swim and then you find your bearings.

Most of the characters in the film represent people who came to bigger cities in the hope that they will soon go back. If they had a choice they would not have come in the first place. They came here because they did not have a choice. But they are hoping that they will go back some day, to their home, to their land, to their families, to their own people. But not many are fortunate enough. I call myself fortunate because I don’t think I would have gone back. I have found my rhythm with the city.

Is the situation of India’s migrant workers unique to the country? Is your film a way of communicating their grievances to political leaders?

Definitely not, it’s not unique to India. The government should do what it should but that is not the point of this film. The idea is to start seeing those invisible people and treating them as human beings. Our society is divided in various ways according to religion, caste, region, language, food habits and whatnot.

At the same time the beauty of this country is its diversity. No other country that I know of has so many kinds of people living together—that extent of diversity may very well be unique to this region. Given such diversity and difference, it will not be easy to remain seamless. That is what this film is all about—the effort it takes to remain seamless. The more seamless we are, the happier we will be.

At the end of the day it is about having a happy life. Either we have it or we want it or we share it.

When you were making the film, did you have to take stock of your own feelings? Did it affect you emotionally?

Of course, it did. Whenever you make a film like this, the mirror is first placed before you. You cannot be dishonest to yourself, and you get to see some not-so-pleasant sides of yourself, not-so-great sides of society and that is what you need to talk about and show.

What kind of effect do you think Bheed will have on its audience? And who do you think is watching the film?

I don’t expect a film to make an impact that will be felt immediately. This film can, at best, pose some questions, point out some facts. I don’t think films have solutions, people have solutions.

The other day I was told that 20 of those who watched the film looked like they were migrant workers. It is a good sign that they are watching this film because it is about them.

Are there any takeaways from the film that you’d like for the audience to go home with?

It is subjective. But the number of messages on Facebook, Instagram and the kind of reviews that are written: everyone seems to have a different takeaway. I don’t think I can control who will take away what. All that I can do is not let you forget. If you made some mistake during that time, God forbid if something like this happens again, you will not make those mistakes again.

One word about the effect people say Bheed has had on them…

Empathy.

(This appeared in the print edition as "The Long Road to Empathy ")