In a pivotal scene from The Kerala Story (2023), four female students—three of them crying—try to process a traumatic incident: One of them has been molested in a mall. The only composed person among them wears a stern expression and a mauve hijab. “I’m sorry guys, but this had to happen,” she says. “Devils need a chance, and you gave them the chance. Thank Allah that he saved you. But did you ever think why, of all the women in the market, this happened to you?” She explains: “Because only you three”—two Hindus and one Christian—“were not wearing hijab. Allah always protects us—he’s not like your gods.”

Nine months later, the “brave storytellers of The Kerala Story” released a teaser, Bastar. A cop—sitting in her office, wearing a bandana—compares the Indian soldiers killed by the Pakistani Army (“8,738”) with Naxals (“over 15,000”). When they “massacred 76 jawans in Bastar”, she thunders, a college celebrated those deaths: “JNU.” She stands up. “Just think about this: a reputed university celebrates the martyrdom of our jawans. Where does such a mindset come from?” These Naxals, she adds, are “conspiring to dismantle India”. Their allies? “The left-liberals and pseudo intellectuals.” She proposes a final solution: shooting the “vaampanthis” (Leftists).

This genre’s poster boy, The Kashmir Files, alternated between the militants in 1990 and the ‘ANU’ students in 2016, drawing implicit and explicit parallels between them. Made on a reported budget of less than Rs 20 crore, both The Kashmir Files and The Kerala Story earned more than Rs 300 crore. Monetary reward, though, is just the first benefit. Second, recognition, via National Awards (The Kashmir Files won the Best Feature Film on National Integration). Third, power (its director, Vivek Agnihotri, who got Y category security detail after the movie’s release, is also a censor board member). Other rewards range from special permissions to politicians’ endorsements to tax cuts. Riding the wave of jingoistic films, Kangana Ranaut has transitioned to politics, representing the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in the 2024 Lok Sabha elections.

If the months before the 2019 elections saw a spate of films demonising the BJP’s villains (The Accidental Prime Minister, Uri, The Tashkent Files), then this year is no different: Article 370, Bastar, JNU: Jahangir National University. “Is JNU a haven for anti-nationals?” Its trailer asks. Followed by the college students shouting, “Bharat, tere tukde tukde honge [India, you’ll be broken into pieces].” Backed by Zee Studios, JNU reproduces the contentious line attributed to Kanhaiya Kumar leading to his arrest—later debunked as doctored—made popular, via countless reruns on TV, by channels such as Zee News. Amid scenes of students’ violence—intercut by “Can one university break the country?”—the trailer throws this line: “It’s easier to get a visa for Pakistan, not JNU.”

Pakistan. Of course. Often featured as a convenient punching bag in Hindi films—also doubling up as a fount for Islamophobia—it has found several companions in recent years, as Bollywood filmmakers have sought villains justifying their Hindu heroes. So the Islamic rulers emerged, then the Congress, then Americans, then, at last, a villain not seen in Hindi cinema before: regular Indians intent on tearing the country from inside—the liberals, the leftists, the intellectuals—so much so that they’re called “terrorists”. Post-2014, Bollywood propaganda resembles a boomerang: It’s travelled the world to reach home.

In May 2014, when the BJP came to power, propaganda cinema was 102 years old—Indian cinema, 101. Its first fictional, feature-length example was Independenţa Românie (1912), based on the 1877 Romanian War of Independence. Soon, World War I—the first conflict in the age of movie cameras—altered this genre forever. In 1916, the British Empire and the French Third Republic fought the German Empire in the months-long Battle of the Somme. They all made (propaganda) films on it. The British movie showed “remarkable ideological constraint”, wrote Nicholas Reeves in The Power of Film Propaganda: Myth or Reality (1999), presenting the events in a “measured, unemotional, and almost objective manner”. The French piece resorted to propaganda-within-propaganda: a war movie made by a country that excluded its ally. The German film answered its British counterpart by claiming its own victory in the battle.

The United States, too, had produced war propaganda—The Battle Cry of Peace (1915), The Kaiser: The Beast of Berlin (1918), Hearts of the World (1918)—but its most famous exponent, like the above Bollywood films, targeted not the enemy outside but the ‘enemy inside’. A racist drama glorifying the Ku Klux Klan, The Birth of a Nation (1915) was a moral failure but an artistic triumph, pioneering such techniques as close-ups, fadeouts, flashbacks, night-time photography, elaborate extras, musical score—and a White House screening.

The next decade saw a new nation greasing its ambition, the USSR, whose founder, Vladimir Lenin, had realised the true powers of cinema. He found an ally in director Sergei Eisenstein whose masterful use of the Soviet Montage Theory transformed both propaganda and world cinema. He used it to stirring results in Battleship Potemkin (1925) and October (1928), dramas commissioned by the Soviet government championing Russian workers and revolution.

On June 30, 1928, a 30-year-old man watched Potemkin for the second time. “This film is fabulous, with splendid mass scenes,” he wrote in his diary. “Technical and scenic shots have incisive penetrating power. And the striking slogans are so cleverly formulated that no one can object. That’s what makes it dangerous. I wish we had one like that.” He was Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi party’s chief propagandist. Much to his satisfaction, Nazi cinema produced a rousing movie with “splendid mass scenes”, Triumph of the Will (1935). A “documentary” capturing the 1934 Nuremberg rally—though Leni Riefenstahl staged several scenes—it used wide frames, aerial shots, and deep focus, producing a majestic, arresting effect. “Riefenstahl was clearly very familiar with Eisenstein’s films,” wrote Alan Sennett in ‘Film Propaganda: Triumph of the Will as a Case Study’, “and used rhythmic montage techniques as well as drawing from Potemkin directly.” The Soviets and the Nazis: divided by ideology, united by cinema.

A few years later, World War II re-energised the genre again. Both the Nazis and the major Allied powers—Great Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union—turned to cinema to mould public opinion, solicit support, and demonise opponents. In 1940, the British government established a propaganda wing, the Film Advisory Board (FAB), in India—a country experiencing its own nationalist churn. The Indian movie press lambasted its head, Alexander Shaw. (“An unknown man,” said the Filmindia magazine, “even in England.”) Shaw resigned in 10 months—“partly because he was not accepted by the Indian industry,” according to film historian B D Garga—and FAB folded soon.

Another propaganda unit replaced it in 1943, Information Films of India (IFI), which made documentaries on, besides the war, the country’s history, communities, and cultures. Five years later, the Indian government created the Films Division (FD), retaining IFI’s employees, aims, and mechanics. Like IFI, FD ordered theatre owners to screen its documentaries (making them pay the rent), provided little independence to directors, and produced films marked by omniscient voiceovers (a ‘voice of god’ style). The Indian government knew what its colonial masters did: that in a country wrecked by a low literacy rate (16% in 1947), cinema was their most reliable—and formidable—ally.

A state-controlled organisation with a long history can’t be homogenous, as it changes with times and regimes. But its Nehruvian phase stands out for an obsessive and unified emphasis on nation building, where many movies used cunning methods and elisions to parrot the governmental agenda, exemplifying ‘benign propaganda’. Such documentaries, many available on YouTube, had varied modes of communication. Their construction of an ideal citizen underscored the importance of selfless individuals aiding the government’s plans. Good Citizen (1959) for example, set in a village, issued a series of instructions: pay tax, cast vote, get vaccinated. Citizens and Citizens (1962) preached what not to do; Say it with a Smile (1960) taught generosity; The Vital Force (1963) urged people to volunteer for a common cause.

Centred on regular Indians, these films barely featured their voices. Instead, the audiences heard the moralising voice of the state. “The viewers weren’t invited to define development in postcolonial India,” wrote Peter Sutoris in Visions of Development (2016). “It was the ‘experts’ who determined the shape of modernity and future directions of the country.” Much like colonial documentaries, Tools for the Job (1943) and Community Manners (1943), FD movies drew a clear through line between conscientious citizens and national progress.

They turned theatres into classrooms and the state into a teacher. And like an unwavering disciplinarian, it warned and punished. Consider The Case of Mr Critic (1954), which lampoons a common man sceptical of the government. The movie not just takes constant digs at him—by turning him into a ludicrous caricature—but also props him up as a cautionary tale (Mr Critic’s constant “pooh-poohing” gets him fired) and a symbol of hope (he uses the same government scheme, which he had earlier rubbished, to find employment).

Like IFI, FD made films on Adivasis. Here’s how New Lands for Old (1952) described them: “The land-hungry invaders spared no thought for tomorrow and hack[ed] high-land forests. In their greed and ignorance, they squandered nature’s resources.” Several FD films on Adivasis “perpetuated colonial-era criticisms of their ways of life,” added Sutoris, “construing them as second-class to the modern middle-class lifestyle enjoyed by the filmmakers and [their target audience], urban cinema-goers.”

If the state could scold, then only could it soothe—like a headstrong father taming a truant. The Adivasis of Madhya Pradesh (1948), the FD catalogue stated, showed how the “government-sponsored cooperatives” made “old, orthodox” lifestyles “modern” and “better”. And if the FD documentaries didn’t rebuke—or reform—the Adivasis, then it exoticised them. Both Our Original Inhabitants (1953) and Gaddis (1970) called their costumes and dances “picturesque”. These films, too, seemed to have no interest in, wrote Sutoris, “hearing Adivasis’ own perspectives about their desire for change and definition of progress”.

FD, on the other hand, trumpeted its own vision of progress, fetishising new muscular symbols, likening them to “temples of tomorrow”: dams, canals, factories. India’s march to industrial modernity in these movies, stated Sutoris, had a homogenising sweep—that one model of economic planning could benefit all Indian villages. Like many FD films, they posited Indian elites as the sole architects of nation building and vanquished all scepticism about such progress (as seen in The Dreams of Maujiram (1966) and Shadow and Substance (1967), where poor Indian farmers were taught patience and shown development, much like Mr Critic).

These films even deceived audiences. They equated almost all economic prosperity to dams, neglected alternative methods to reach the same goals, and ignored the dams’ human and ecological costs—in terms of both material (the displacement of villagers) and psychological (the loss of livelihoods, homes, identities). Some documentaries that addressed those concerns, wrote Sutoris, such as River of Hope (1953), painted an extremely optimistic—and unrealistic—picture of rehabilitated villagers. “These films show that in the postcolonial development regime, some colonial approaches to filmmaking not only survived Independence but indeed snowballed into cinematic representations of development whose fallaciousness surpassed even that of colonial-era documentaries.”

In the early ’50s, as the Cold War began to boil, propaganda cinema welcomed a new protagonist, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Deploying an unusual ‘ally’, George Orwell, it dictated the film adaptations of both Animal Farm (1945) and 1984 (1949) by altering characters, scenes, and conclusions, making them anti-Soviet mouthpieces. A book that warned against ‘thought control’ had now been weaponised to perpetuate it. The Agency then ‘adapted’ Graham Greene’s bestseller The Quiet American (1955), an anti-war novel that questions America’s involvement in Vietnam, and made it—what else but—anti-communist. CIA’s Hollywood agent, Carlton Alsop, ensured that American films beamed racial harmony (countering the Soviet message that America was racist). So, through his contacts with casting directors, wrote Frances Saunders in Cultural Cold War (1999), he regularly planted “well-dressed Negroes” as extras but in a way that they didn’t look “too conspicuous or deliberate”. He also sanitised the climax of Arrowhead (1953), removing all references to the US government’s terrible treatment of the Apache tribe.

The CIA’s covert propaganda peaked in the ’50s and early ’60s, noted Tricia Jenkins in The CIA in Hollywood (2012), “but declined by the end of the decade”. And by the early ’90s, with the dissolution of the USSR and a series of intelligence failures and negative portrayals in Hollywood, it faced a threat to its very existence. So, in 1996, it established an entertainment liaison office in Hollywood and appointed Chase Brandon—a veteran Clandestine Service officer—as its head. The CIA had a simple message for filmmakers: Want our co-operation in making movies (such as access to facilities, officials, and files)? Then let us approve the script. It had adopted the playbook of the Department of Defense which, providing military weapons and shooting locations at subsidised costs, often shaped—and controlled—films. (The Indian Army, as preoccupied with its image, refused to give the No Objection Certificate to a film in 2022, as it showed the armed forces in “poor light”.)

Brandon’s collaboration with Hollywood produced many movies and TV shows, glorifying the CIA, such as In the Company of Spies (1999), The Agency (2001–2003), 24 (2001-2010). These depictions also functioned as recruitment videos, helping the Agency increase its enrolment (which had seen a sharp dip in the last decade). It also nurtured relationships with film stars, most notably Ben Affleck who, besides playing a CIA analyst in The Sum of All Fears (2002), directed the factually dubious Argo (2012), which won the Best Picture Oscar whose announcement was broadcasted straight from...the White House.

The recent Bollywood propaganda screams even when it whispers. Many films make it clear, right from their trailers, that they’re “based” on or “inspired” by “true events”.

And in 2011, the Agency got its best ‘propaganda gift’: Zero Dark Thirty (2012). The CIA gave unprecedented access to the makers—revealed a Freedom of Information Act request—while filmmaker Kathryn Bigelow returned the favour, treating the intelligence officers to expensive dinners. Once, while dining with a female CIA officer, Bigelow gifted her black Tahitian pearls. (She gave the jewellery to the headquarters to get it appraised; it turned out to be fake.) The CIA-Hollywood symbiosis seemed especially disconcerting in this case, as the war drama implied that torture tactics had led to Osama Bin Laden’s capture.

Sometimes the CIA outdid itself, as The Agency’s creator, Michael Breckner, found out. Over many ‘informal chats’, Brandon pitched several ideas to Breckner who incorporated them in the screenplay. Its pilot, for instance, Breckner told Jenkins, “was based on the premise that Bin Laden attacks the West and a war on terrorism invigorates the CIA”. (Breckner finished writing that episode in March 2001—six months before 9/11.) Chase suggested other subplots as well: a Hellfire missile fired from a drone on a Pakistani general, an anthrax attack on Americans, and a Russian suitcase bomb stolen from the USSR. “All these events,” said Breckner, “happened shortly before or after these episodes aired.” Reflecting on his conversations with Chase, Breckner believed that the CIA was “attempting to test the waters somehow”—or “using the series to workshop threat scenarios”.

The recent Bollywood propaganda, in contrast, screams even when it whispers. Many films make it clear, right from their trailers, that they’re “based” on or “inspired” by “true events”, which have been suppressed for long. These movies, then, become a collaborative exercise—between the filmmakers and the audiences—in fact finding. They further that charade by using archival footage, newspaper clips, shocking stats, infusing journalistic spirit in dramas hostile to facts.

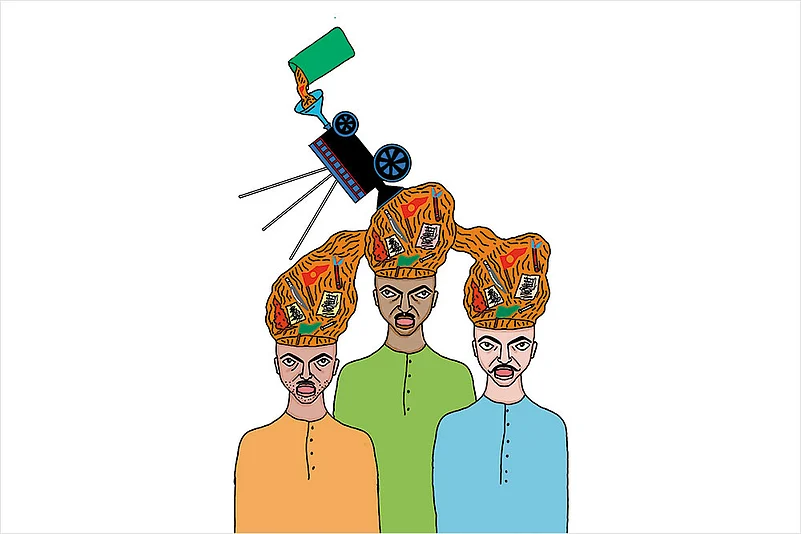

They’ve also polished their style. Uri (2019), Thackeray (2019), Tanhaji (2020), Swatantrya Veer Savarkar (2024), among others, have impressive cinematography, editing, and performances. An early scene in Thackeray uses an ingenious match cut: the judge striking a gavel on the bench cuts to karsevaks hammering the Babri Masjid—two Indias, two verdicts. In Swatantra Veer Savarkar, a young freedom fighter, Madan Lal Dhingra, proclaims “Vande Mataram” before a noose. After setting up the premise—that violence is necessary, noble, and patriotic—the next scene shows Mahatma Gandhi saying, “Ahimsa parmo dharma [non-violence is the prime duty].” Two independent shots, a clever juxtaposition, and a new meaning: this is Soviet Montage cinema—or the Kuleshov Effect—serving the Hindu rashtra.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

The astounding success of The Kashmir Files and The Kerala Story has told producers that they can risk less and aim high—and it’s this return on investment, along with possible political benefits, that’s made this genre explode. These movies also don’t need popular actors because in them the state—and its most commanding embodiment, Modi—is the real star. Maybe some directors have—finally—understood that in a powerful (or, well, divisive) film the main star is the storytelling itself. What excellent art-house cinema couldn’t teach Bollywood, hate-mongering did.

As Bollywood has increased its propaganda production, like Nazi cinema, hunting enemies inside the country, it’s also manufactured heroes whose prime identities have changed from Indians to Hindus to Hindutvavadis. A biopic on a prominent Hindtuva ideologue, Deendayal Upadhyaya, starring Annu Kapoor, is in the making, while another on the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) founder, K B Hedgewar, will release in 2025, coinciding with the organisation’s centenary year. Even M K Gandhi hasn’t been spared. Last year, Gandhi Godse—Ek Yudh imagined a ‘sober’ conversation between the man and his murderer. A year before, Why I Killed Gandhi, an OTT release, gave inordinate screen time to Godse who called himself secular and a patriot. Another courtroom drama, I Killed Bapu (2023), defended Godse. Hindi cinema’s current tryst with history and bloodthirst has reached its logical conclusion: for every bit of gandh—or dirt—in Gandhi, it sees a God in Godse.

(This appeared in the print as 'The Propaganda Files')