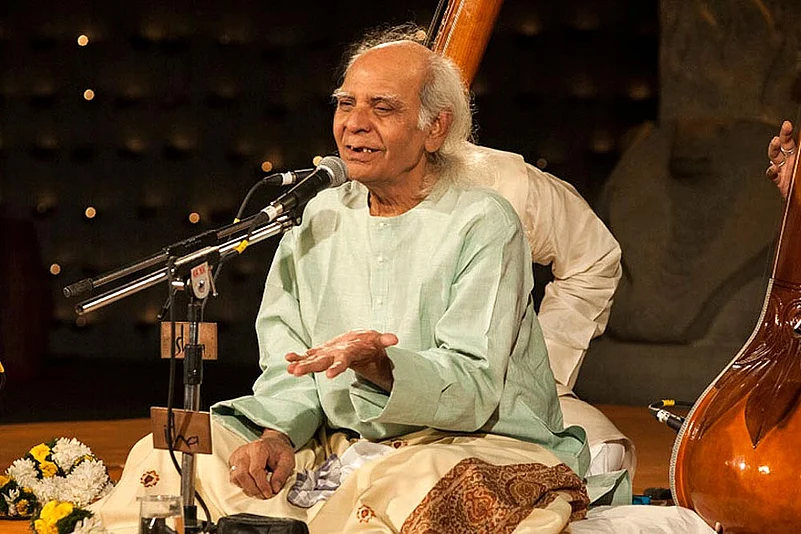

An allusion to yogic motifs is not out of place when it comes to dhrupad. That same concentrated immersion is here, that same rigour, that passage along the mind-body continuum. People often don’t realise how physical the practice of music is. Sayeeduddin Dagar used to say it’s the body that holds aloft the first half of a classical musician’s life. It’s in the latter part that the transphysical hopefully takes over, a kind of mellowness, an awareness of other ways of seeing and feeling, a riper idea about the form and its interior expanse of beauty.

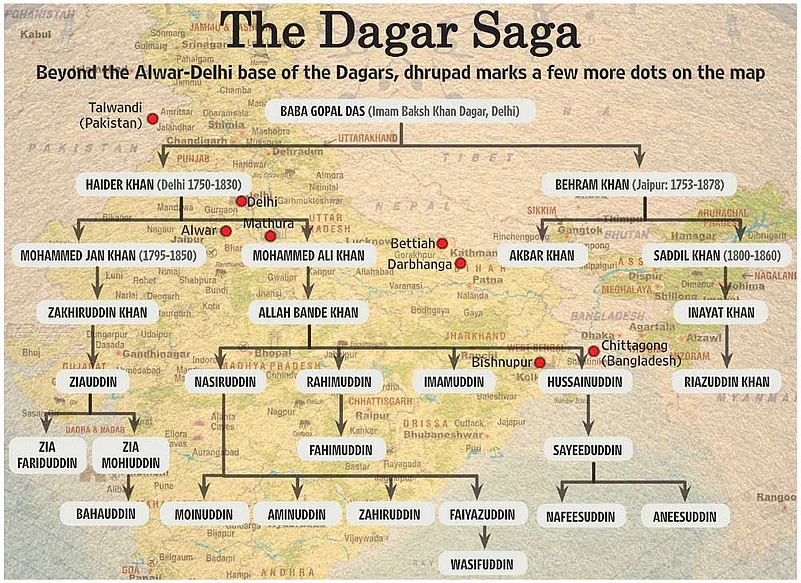

When Ustad Sayeeduddin passed away—aged 78, on July 30—a long, unbroken silken thread of India’s history reached its end in some ways. A parallel history borne on sound, burning like a holy wick in a small alcove, emitting dancing flames that could astonish songbirds, as the poet said. Sayeeduddin was the last singing member in the illustrious 19th generation of the Dagar family. Yes, there are newer generations, with serious-minded practitioners sworn to tradition—yet rooted in the new world, a new milieu, with modernity and recorded music having changed the landscape. Sayeeduddin, born in Alwar, Rajasthan, in the summer of 1939, also breathed in the old world in whose womb this genre and its aesthetics were groomed.

And yet, Sayeeduddin too bears traces of the transition. Though steeped in that strict discipline and its meditative mode, he was also blessed with an incredibly sonorous timbre—a trait not always central to a system that’s not meant to yield its pleasures easily. As poet Ashok Vajpeyi says, “He looked at the dhrupad courtyard through the khayal window.” That ever-so-slight nod to a relatively more free-form pursuit of beauty, though, was anchored in the Dagars’ almost ascetic focus on voice culture—a mastery of varying sound production from the chest and navel.

“Sayeeduddin was an exponent of that,” says musicologist Manjula Saxena. “So silken does the voice become that nuances are heard best.” From the deepest bass drone to the faintest trill, all of it rose out of his body like incantation, never slipping into the banal or flirtatious: his voice ranged within a zone held down by a meditative silence. As it should be in dhrupad, the subcontinent’s oldest surviving classical music genre, of which the house of Dagars is one of the original authentic schools.

Dagarbaani, in fact, is the only one left among the four canonical ‘baanis’ of dhrupad, with Gauhar, Khandar and Nauhar having long petered out or mutated—at best finding distant echoes in a few styles that exist precariously along northern and eastern India. The Darbhanga stream, for instance, has elements of Gauhar and Khandar, according to its exponents, while that same Indo-Nepal border belt features the Haveli-style Bettiah, whose lone master is struggling to sustain his lesser-known school. Eastward, Bishnupur in Bengal essays a similar picture of obsolescence. The Mathura-Vrindavan stream nurtures only simpler pada—and not the challenging 14-beat dhamar compositions or the rhythmic nom-tom or detailed alaap that are dhrupad highlights. Across the borders, the Talwandi gharana of Pakistan is desperately seeking to energise its dregs—much like in Bangladesh.

In post-Partition India too, dhrupad was facing a bleak future—until two Dagar brothers began popularising the esoteric genre. With just the pakhawaj marking complex time in a field of repose set out by the stark drone of tanpuras, the spartan dhrupad had been fast losing its foothold on the Hindustani music map over two centuries owing to the emergence of khayal, which permitted colourful improvisation and ornamentation. Moinuddin and Aminuddin Dagar freed dhrupad from its air of staidness, while holding to the fundamentals of slowness and sonority—features dating back to the days of the system’s pioneering patron, Raja Man Singh Tomar, who ruled Gwalior for three decades from 1486, its rudiments flowing from the rhythmic Prabandha chanting of Hindu scriptures from the 1st century AD.

After Moinuddin’s early death in 1966 at age 47, there emerged the famed Saptak—seven exponents from the family that had converted to Islam, apocryphally, after their Brahmin forefather Gopal Das Pandey was ostracised for accepting paan from Delhi’s Mughal emperor Mohammed Shah Rangila (1702-48). The Dagars found their next vocal pair in brothers Zahiruddin (1933-94) and Faiyazuddin (1934-89). Zia Mohiuddin (1929-90) played a crucial role reviving the difficult rudraveena, while his vocalist cousin Rahim Fahimuddin was 74 when he passed away in 2011. Two years thence came the death of Fariduddin, 80, by which time Dagarbaani had an array of disciples outside the family.

Sayeeduddin learnt from each elder cousin, besides his father Hussainuddin Dagar. For all the heaviness of the system he was initiated into, he was a light-hearted, jovial man. “Uncle used to play cricket and carroms with us,” recalls Bahauddin Dagar, who carries forward his father Mohiuddin’s rudraveena legacy. Sayeeduddin was also deeply interested in literature, especially poetry. “That gave him a self-learnt perspective about life.”

The Dagar Saptak in the early 1980s

The moustachioed Bahauddin, now 47, appears as a thin pre-teen almost dwarfed by his instrument—a five-foot-long wooden cylinder, with two large, round resonators—in Mani Kaul’s 1982 documentary, Dhrupad. A time when many had begun worrying whether dhrupad—its gurukul ethos grappling with modernity—was on a ventilator. That mood fills the 70-minute film, shot in the semi-arid expanses of north-central India, dotted with brooding forts.

If Bahauddin mans the turrets of Dagarian dhrupad in Mumbai, the mantle in the capital now falls on vocalist Wasifuddin, 49. “We now see the results of the dedication of our seniors,” says the son of Faiyazuddin. “Youngsters keep approaching us. Half-a-dozen among them are good…they will shine. It’s a happy contrast to the scene when I began the rigour in the 1970s.” The gloom of those days had prompted Rahim Fahimuddin to lament that “even khayal musicians snub us” and Fariduddin to blame a general impatience towards the form’s nuances.

Sayeeduddin is now entombed in Jaipur, where he spent life till middle age before moving to Pune in 1984. Two of his sons are keen to carry forward the legacy. “We used to be so restless as little boys when father would pin us down to long hours of riyaz (practice),” recalls Nafeesuddin, mourning alongside Aneesuddin. The tanpura’s drone, though, was gripping. The duo debuted in 1999 at their ancestral house in Jaipur—named after the baani’s real founder, Behram Khan Dagar (1753-1852), son of Gopal Das (later Imam Baksh Khan).

One of the Dagar Saptak’s stellar contributions was coopting disciples beyond the clan. In 1981, two young siblings from Ujjain started learning under Fariduddin and Mohiuddin. Umakant and Ramakant went on to gain fame as the Gundecha brothers, and are always busy popularising dhrupad across India and—like their peers—abroad. “It’s a radical change,” gushes Umakant, who has been running the Dhrupad Sansthan with his brother on the outskirts of Bhopal for about two decades now.

It’s a picture of bustle. The Sansthan has chapters in six cities now, including Kathmandu. “We’ve had students from some 35 countries and have groomed quite a few young masters in vocals, as also rudraveena, esraj, flute and even saxophone, besides pakhawaj,” says Ramakant. “Techies are quitting jobs to learn under us. Also, lawyers, filmmakers, bankers…” Bhopal also has a state-backed Dhrupad Kendra, set up in 1981 following efforts by poet Vajpeyi and filmmaker Kaul.

The Dagar seed has spawned other zones of serious dhrupad—from Ritwik Sanyal (who taught at Benaras Hindu University) to Nirmalya Dey to the relatively younger Uday Bhawalkar. Dagarbaani even inspired the IITian Kiran Seth in 1977 to float SPIC-MACAY on his return from the US, opening up Hindustani classical to younger audiences. The Dagars also broke a barrier by teaching females. At Santiniketan, Kaberi Kar says she owes her dhrupad skills to Aminuddin and Fahimuddin’s Calcutta stint. “Not just me. The famed Falguni Mitra, Aloka Nandy, Ashoka Dhar…all have taken taleem under the Dagar brothers,” she adds.

Kaberi lists out her Visva-Bharati students: Ashoke Barman (Arunachal Pradesh), Keya Banerjee (Siliguri), Asit Roy (teaching in Bangladesh’s Rajshahi University) and Mamtaj Begum of Dhaka…. East Bengal does have a dhrupad heritage—Mohammed Hussain Khasru of Chittagong, Munshi Raisuddin of Khulna and Gul Mohammed Khan, who sang at the inaugural of Dhaka Radio in 1939—but has only a marginal presence now. Even the western part of the partitioned land can’t claim a vibrant scene, laments Ira Mukherjee, a Fahimuddin disciple. “No point comparing gharanas. Dhrupad in Bengal is highly indebted to the Dagars,” says the visiting professor at Delhi University (DU).

A full-fledged dhrupad wing hasn’t been easy to institute at DU, says Delhi gharana khayal exponent Krishna Bisht, who retired from its music department. “We did try on and off to get dhrupad students, but the number of applicants fell terribly short of the quota. Shruti Sadolikar teaches dhrupad in Lucknow’s Bhatkhande Deemed University,” she adds. “As for females, the last century had dhrupadiya Sumati Mutatkar in full glory. Asgari Bai, equally veneered, sang, but remained confined to her part of Bundelkhand.”

Asgari Bai

In West Punjab, Talwandi had brothers Labrez Afzal and Ali Hafeez in a gharana that’s seen as a cousin of Darbhanga. (The latter, of course, is the big one after Dagar—embellished by Mallick family greats such as Ram Chatur, Sukhdev, Vidur, Abhay Narayan and Prem Kumar besides Balaram Pathak and Siyaram Tiwari.) The Talwandi siblings clung on tenaciously to the legacy of 1913-born Mehar Ali Khan, who was groomed under Harcharan Singh of Lyallpur, off Faisalabad. Partition left them orphaned, as the Sikh family moved to India, says Lahore-based scholar Khalid M. Basra. After Hafeez’s death in 2009, Afzal is the lone torch-bearer of Pakistan’s only dhrupad gharana. Though the visually-challenged Aliya Rasheed of Lahore, who came all the way to Bhopal to learn under the Gundechas, teaches at the National College of Arts back in her city.

The female line is like a rarity within a rarity. Mutatkar (1917-2007) used to protest dhrupad getting dubbed as a museum piece. “Classical music lovers speak highly of it, but rarely pay a genuine ear,” she said at a symposium in 1997, where the late critic Raghava R. Menon urged dhrupadiyas to “dismantle your ivory tower”. Notwithstanding the legacy of Mutatkar and Asgari (1918-2006), who got a Padma award in the evening of a life spent mostly in oblivion, the domain hasn’t been easy for female musicians to even enter. Madhu Bhatt Tailang, Rajasthan’s first woman dhrupadiya, cannot but forget the obstacles she had to weather. “Connoisseurs kept saying a lady’s throat would be too fragile to produce the heavy gamaks,” says the daughter of vocalist Laxman Bhatt Tailang. “Things are better now.”

Another story of disproval came from the Deccan. Dharwad’s Jyoti Hegde was told by masters that rudraveena would be too heavy on her slender shoulders. “I was indignant, but channelled my bitterness into learning the instrument that had fascinated me no end. I meant to start no revolution,” she remarks, tongue-in-cheek. The playing position of the (10-kg) instrument, she adds, possibly strains the uterus. “That said, I have a 32-year-old son.”

Rudraveena player Jyoti Hegde of Dharwad

In Calcutta, Bishnupur school sitarist Mita Nag explains her struggles to organise annual concerts and workshops at the Gokul Nag Foundation, founded in 2002 in the memory of her dhrupadiya grandfather. “With little government support, we largely rely on corporate houses. The first task is to convince honchos that there exists a system called dhrupad,” shrugs the daughter of septuagenarian sitarist Manilal Nag. “Unless big names feature, the programme seldom gets sponsors.” Dhrupad also features in the monthly shows organised by archivist Shabana and Imran Dagar, of the family’s 20th generation, under the Ustad Imamuddin Khan Dagar Society in their native Jaipur besides Delhi.

Other sitarists too echo the sobriety of dhrupad, acknowledges Prateek Choudhari, son of Senia sitarist Debu Choudhari, 82. “Our line avoids the light-sounding kharkas, murkis and other needless decorations. Straight lines are perhaps tougher than zigzag,” says the DU teacher. “We do it like the dhrupadiyas do it on surbahar.” Surbahar used to be the specialisation of 90-year-old Annapurna Devi, first wife of Pt Ravi Shankar and daughter of the iconic Baba Allauddin Khan. This bass sitar, with wider frets and a dried-gourd resonator, has a grainy sound that suits the dhrupad ethos, like the rudraveena. “The naturally lower pitch adds to the sobriety. Restraint is the essence of dhrupad,” says Mumbai’s Pushpraj Koshti. Surbahar counts among its masters Imrat Khan of Etawah’s Imdadkhani gharana, who turned down a Padma Shri this year for being “too late”, and his five sons, besides Ujjalendu Chakrabarti, Shubha Sankaran, Kushal Das and Ashok Pathak.

Westerners have taken to dhrupad too—Brian Silver, John Perkins and Matyas Wolter, for instance, play the surbahar. The German Carsten Wicke lives in India, playing the rudraveena. He learned from a master no less than Ustad Asad Ali Khan (1937-2011). Asad Ali’s adopted son Zaki Haider carries forward their Khandar style. Former Belgian diplomat Philippe Falisse was trained under Bishnupur’s Satyakinkar Bandhyopadhyay; he married locally too, falling in love also with Bengali literature. Sayeeduddin’s French pupil Jérôme Cormier too is a vocalist.

The West’s exposure to Dhrupad began in the 1960s, courtesy the senior Dagar brothers, who travelled widely. Scholar-author Deepak Raja estimates that 80 per cent of money into dhrupad comes from abroad. “It’s an Indian-origin system funded from abroad,” he says. Late musicologist Ashok Ranade described dhrupad as an “enigma” in cultural anthropology: “Never before has a genre of art music, pronounced dead in India, experienced so shaky a revival with home audiences and become popular with alien audiences to become so largely dependent on them.” Pakhawaj exponent Dalchand Sharma of Nathdwara acknowledges the revival of the past quarter century, but feels dhrupad still lacks concert space. His colleague, Mohan Shyam Sharma, who has accompanied Sayeeduddin in “over 400 concerts, many of them abroad”, too says dhrupad may have come out of its most difficult phase, but the obscurity lingers.

No wonder Indra Kishore Mishra, 61, of Bettiah, in interior Bihar, finds it hard to get students other than two family members. Erudite vocalist Falguni is keen to “integrate” all four gharanas while carrying the Bettiah label. Not far away, Darbhanga’s Prem Kumar Mallick is happy that inter-gharana spats have largely abated. “We participate in each others’ music festivals,” says Prem, who lives in Allahabad, taking pride in his vocalist sons Prashant and Nishant. Prof Sanyal’s son Ribhu is also renders dhrupad.

What of cross-genre play? Dhrupad-Carnatic collaborations do happen, says Mathew Joseph, a student of Umakant-Ramakant. The Gundechas sing with Vijayawada’s Malladi brothers. “After all, the ragam-tanam-pallavi of the south has a parallel of sorts up north,” observes vocalist Guruvayur T.V. Manikantan of DU. Adds chitraveena exponent N. Ravikiran: “The embellishments, though, aren’t alike.” A solitary realm, then—with obscurity almost built into it. In a Doordarshan documentary not too long ago, Sayeedddin had said, “One day dhrupad will be imported to India.” If something could evoke a sense of doom close to that, his own going may be it. No one can bring back those 20th-century masters now. “We now have no elder to criticise the nonsense we play,” says Bahauddin.