The most popular musician of Shillong, UN Sun— U in Sun sounding like u in “Kung Fu”—is difficult to trace.

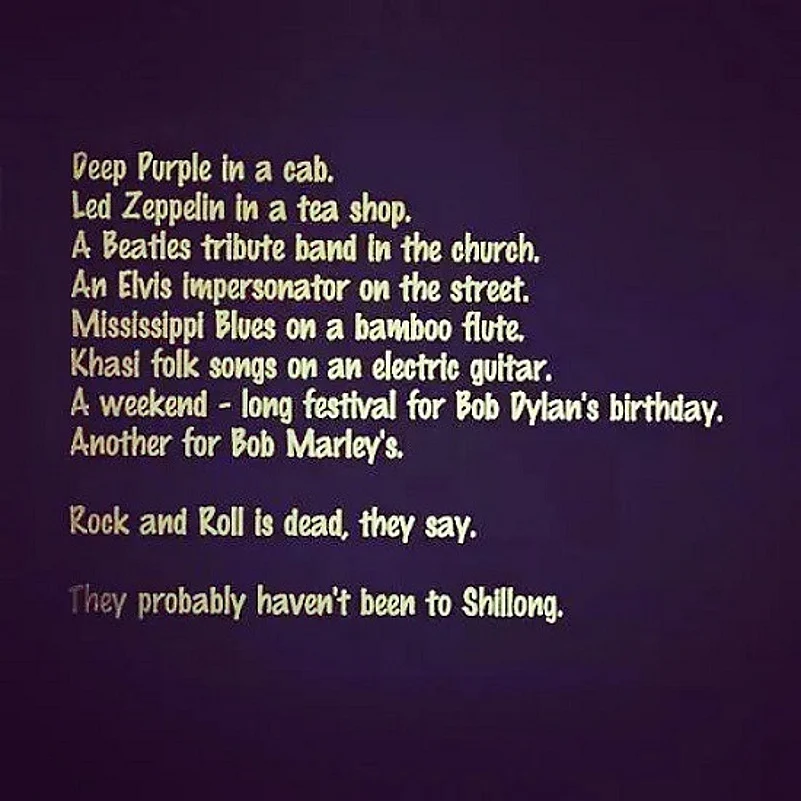

Asking Shillong music scene regulars elicits surprised disdain. UN Sun is not on their throbbing playlists of bands and music from around the world. K-Pop is Korean, not Khasi Pop. Theirs is a world of global and national networks, where local is just a curiosity to be sent floating across as a meme, to share and show off. This is the latest version:

Deep Purple in a cab

Led Zeppelin in a tea shop

A Beatles tribute band in the church

An Elvis impersonator on the street

Mississippi Blues on a bamboo flute

Khasi folk songs on an electric guitar

A weekend-long festival for Bob Dylan's birthday

Another for Bob Marley's

Rock and Roll is dead, they say.

They probably haven't been to Shillong

Translation:

Look, you Indians, Shillong may be an insignificant chhota-mota town of Bharatvarsha far away from the centres of power, a Desolation Row, but we’re the “Rock Capital of India”. We memorialise Dylan in sparsely attended birthday bashes, belting out ‘Forever Young’ year after year. Taxis may overcharge us, but they are still Highway Stars.

Basa Khaw/Rice lane of Iewduh, traditional Khasi market around which British established Shillong town.

Starting its life as the “Scotland of the East”, and now the Rock Capital of India, Shillong has always tried to live its life as an image in a tourist circuit. But this Rock’n’Roll-topia is just a tourist brochure masquerade. A global gloss over local reality, a franchised wet dream. Taxis of Shillong may offer you Deep Purple if it is your (un)lucky day, but more often than not, they would be found playing the songs of local tribal Khasi artists like UN Sun, Anthony Kongwang, Rana Kharkongor or bands like Snowhite. (And anyway Shillong is not Meghalaya, like Delhi is not India.)

A popular mythologizing meme about Shillong

How difficult can it be to locate Bah Sun? Touristy Shillong almost refuses to know him and vernacular Shillong seems to have no idea where he could be. They know his songs, they can quote them, they can sing them, wield them for rituals of seduction, but they don’t have any idea who or where Sun is.

An event manager—who has just organised a successful beat contest—is irritated that I am looking to write on UN Sun. Why him? Isn’t he the guy who specialises in writing vulgar songs in Khasi, with electronic tracks? I am not surprised that ‘vulgar’ for him is dirty and pornographic, not as it once was in Latin—“of the common people”.

He is into cultural export-import. Vulgar does not interest his sponsors. “Anyway, you won’t find him in Shillong,” he tells me. “He is from Sohra.”

Sohra is the Khasi name for Cherrapunjee, the wettest spot in the world, the site of innumerable travel documentaries. A damp collection of localities that many years ago lost out to Shillong in being chosen the administrative capital of this Scotland of the East.

But Sohra was no address for UN Sun. I was not going to find him there. He is from Laityrah, a village close to Sohra.

“He sold his house here sometime back and moved away,” I am told. But moved away where?

II

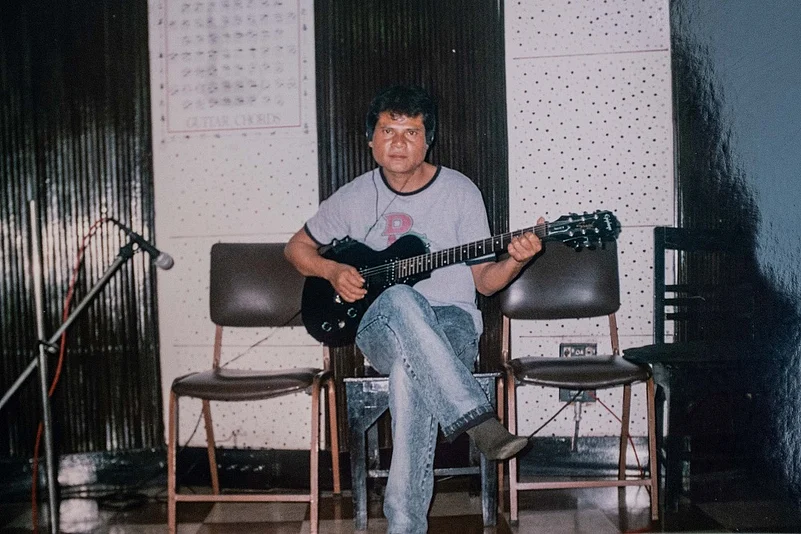

U N Sun with Sohra/Cherrapunji hills in the background. Source : from the family album

I heard of Sun 10 or 12 years ago. His album Mama Kahan Hai (Where is Uncle) was a hit. Rumour had it that the album had sold a lakh cassettes, which means 10 percent of the Khasi population had bought it. The title song was a tartly observed routine, posed as a set of questions to a Khasi woman conned into a marriage by a non-tribal man, so as to get benefits which tribals are supposed to get in the Tribal majority land of Meghalaya:

Mama kahan hai?

Mama kahan hai?

Mama kahan didi?

Bindi nahin laga

Bachcha bhi zyada

Jaane kahan jayega

(Where is Uncle, sister? He didn’t really marry you, but gave you many children. Where will you go now?)

Being a non-tribal dkhar dating a local Khasi girl, I was a perfect Mama target. Although a feminist and multiculturalist’s nightmare, like any popular artefact, Mama Kahan Hai managed to voice a deeply held opinion amongst the locals, that being a tribal state did not mean ache din for the locals, for it was the non-tribal who continued to control the economy by subverting laws meant to protect tribal interests.

For the Shillong elite, Mama Kahan Hai was an itch that they could not get rid of. It was pandering to the baser instincts of the great unwashed. This was not the kind of musical image they were comfortable with. If the vernacular existed for them, it was in the various odes to this green and pleasant land, preferably with mandatory obeisance to God and morality to grace the officially sanctified evenings.

Modern popular Khasi music coming out on audio cassettes escaped the control of local cultural arbitrators of taste and patronage. In the past, singers had to depend on mostly officially funded functions or All India Radio, or if you were lucky, those companies from Calcutta and Bombay, to get their compositions out. Now, they could raise money and record their songs and allow the popular taste to decide what was heard. They could be playful and honest.

III

“Why don’t you go to Iewduh and ask for him then?” My wife notices my frustration. Iewduh, or Burra Bazaar as the dkhars call it, is the nerve centre of Vernacular Shillong. Shillong would have been called Iewduh but for the fact there already was Ido in Japan and the Brits did not want their sanatorium to be confused with Japan’s capital. This ancient market, still run by the traditional chief of Mylliem, is the Shillong most of the countryside locals encounter. Beyond the glass-fronted Police Bazaar, with its brands and fast food, Iewduh is a maze of mucky narrow lanes which eschews fashionable footwear.

“If you want, I’ll come along,” my wife sweetly offers.

From millet to mp3 players, cheap smartphones, bows and arrows, beef and boomboxes, Iewduh supplies all that a working person needs. We are looking for music shops. Nestling in the Basa Khaw Khasi or Lane selling local rice, we find Rudolph Mawlong’s shop, Virgo Music. Rudolph is the star of the Khasi film industry, winner of the Best Actor Award at the first Khasi Film Awards. Here, he sits surrounded by VCDs and DVDs of the latest Khasi music albums and films. And he is helpful. “Bah Sun,” he uses Bah, an honorific, “he is not only the most successful Khasi singer, but he also made the biggest Khasi hit film, Khunswet ba Shempap (Orphan of ill fortune)”.

What’s the reason for his success, I enquire. Rudolph smiles his romantic hero smile and says what is common knowledge in this part of town. “He has guts; Bah Sun is gutsy. In his songs, he says what no one else dares to say. Remember his song ‘Statue Mahatma Gandhi’? He did not even spare the politicians and officers sitting in the Secretariat.”

I know the song - a ferociously witty description of the government secretariat in Shillong with the mandatory statue of Mahatma Gandhi in front of it. In Bah Sun’s words, the secretariat is so full of corruption that even the statue of Mahatma Gandhi has turned his back to it. Turned his back or showed his arse, if you choose to hear the naughty innuendo.

Although he doesn’t know Bah Sun personally, he manages to find a phone number that he thinks belongs to U N Sun.

IV

A woman answers the phone.

“Can I speak to Bah U N Sun?”

“He is sleeping.” She is curt, but I am not ready to let go.

“Can I call later?”

“Why do you want to talk to Bah Sun?” I go on about my fascination with his music, his popularity, his guts, my desire to meet him and if possible, interview him. I sound like a job seeker in front of an interview panel.

She lets me go on till I’ve nothing more to say. “I don’t know about meeting. He is sick and bedridden for the last three years. But I will ask him when he wakes up. Call me in the evening.”

I try to imagine UN Sun bedridden. My only image of him is the music video of ‘Jalieh-Jadoh’ (Plain Rice-Pork Rice), where his middle-aged body confidently cavorts with his young love, promising her anything she wants—plain rice or pork rice, fruit or vegetable. And she has to decide fast, before her colours fade away and only wolves grab at her.

I call up Wanphrang Diengdoh of the band Tarik. Tarik are the bad boys of Shillong music, provocative and angular. From the respectable Shillong, Tarik has been trying to smuggle in disreputable Shillong into their music. They’ve done a cover of ‘Jalieh-Jadoh’.

I tell him about Sun. He is shocked. “Boss, Sun was the only musician from our place who was singing about the place. Look at ‘Jalieh-Jadoh’, an infectious beat with images which are so Khasi.”

He is right. Try imagining Shillong from the songs of the English bands, and you would come away disappointed. So why does respectable Shillong ignore UN Sun?

“I tell you, they listen to him, but like some illicit and shameful secret.”

VI

I am summoned. The Lady on the phone is clear that it is not an interview. Bah Sun wants to meet me first. And then she proceeds to prepare me for the meeting.

He is suffering from Central Pontine Myelinolysis, a neurological disorder. He lives in his mother-in-law’s house. He needs constant care. He can get slightly confused with dates and facts, but at least he can talk now. He has also developed an interest in the Bible and looks forward to visits from Pastor Bantei.

“Pastor Bantei…isn’t he the popular televangelist?” I knew him. Before his success as the local religious star, he was an aspiring singer.

The only time Bah Sun ever gave an interview to a local Khasi paper, his condition worsened, so I should not raise my hopes. Bah Sun is superstitious.

VII

Fencing of the house where U N Sun lives with his wife

They live in one of those new lower-middle-class localities of Shillong. It is not a roadside house, but is perched on the hillside accessible only by steps. It is raining and she waits for me. She is apologetic and I am out of breath.

A small concrete structure ringed with a garden. UN Sun is on the ground floor, in a small room neatly curtained with lace. Confined to his bed, with tubes peeping out from under the covers, he is engrossed in watching football on TV. He haughtily stares me down as I say hello and mumble my introduction.

He has put on weight. She brings out her mobile to show me his picture taken in the hospital. He was skeletal and in diapers. He is engrossed in the football while his companion cheerfully gives me his health bulletin with all its corporeal details.

He still has not spoken.

I comment on his Mohawk. She laughs and tells me that she loves doing his hair, like footballers and music stars. He smiles and tells her something. A register is brought out. He has done more than 40 albums. He was trying to do a list with her. “He can remember some, but not all.”

So when did he begin? How did he begin? Where? What kind of music did he want to do? Bah Sun finally speaks.

“I always sang Khasi songs. My own songs.” His speech is slurred but his intention is precise. He is not like the musicians in Shillong trying to perfect their covers. “I never copy songs,” he says.

“Don’t know my date of birth, maybe I don’t remember—I must be forty, but I remember when I recorded my first album…1989 in Calcutta.” Is he putting me on with all this memory business? Is he trying to fit himself into a narrative archetype? How a pop musician is supposed to be? But at least he is talking to me, so I let my cynicism be rewritten.

“I have a friend from my village, who put up the money for my first album. He is a contractor.”

He travelled to Calcutta to record at Usha Uthup’s studio, hard cash in hand. The recording studios in Shillong were not good enough, and everyone knew Usha Uthup. She was a regular visitor to Shillong. But more than recording quality, it was the mass cassette reproduction technology that Calcutta had to offer. He got the phone number of the studio from Rana Kharkongor, the first Khasi singer to get into the cassette business and he flew to Calcutta.

“You know how the trains are. People told me that police trouble the travellers from this part and I was carrying lots of money.” This was his first journey outside Meghalaya. He was just 20. He stayed in Calcutta for a year in cheap rooms, recording, improving his guitar technique and developing a taste for biryani.

He came back with boxes of Er Pyngngad ki Aw and started hawking it around the music shops in Iewduh and various weekly markets outside Shillong. It was a success. He sold 40,000 copies, prompting him to bring out five more volumes.

“I am a woodcutter’s son,” he proudly announces. “I come from a poor family. I only did bylla of music.” He uses the Khasi word ‘bylla’, meaning daily wage labour. “Everything I became was because of music. But I spent it all for this illness. Now I depend on my mother-in-law and my wife.”

He laughs, and so does his wife. She tells me that his biggest selling album was called Kiaw Khasi (Khasi Mother-in-Law). For a Khasi Male in a matrilineal society, where you leave your own mother to live in your mother-in-law’s house, a kiaw can be a formidable presence!

“I sold the rights of Kiaw Khasi for two lakhs to a Marwari—I don’t know, maybe he was Punjabi. He had a shop near Sohra taxi stand called Music King.”

I am curious to see the tape. I wanted to know the song list. He looks at his companion. He doesn’t have a copy anymore. When he fell sick, his immediate family abandoned him. He was in no condition to think about his oeuvre or archive. He had forgotten everything.

“He was like a baby,” she tells me. She had to do everything for him, even teach him to speak again. Everything he made from music and films, all spent.

“You know how much adult diapers cost?” she asks.

Although he lies penurious, he is not yet Below Poverty Line, an official statistic which opens the government coffers. He is not a national treasure providing the diversity in “Unity in Diversity”, when tribals do their designated Republic Day song and dance. He is just a pop singer without patrons or pretensions of culture.

Tea is brought. Plain cakes and biscuits. Bah Sun is given a bib. He sips his tea.

What does the U in “UN” stand for?

“U Bard Sun,” he answers. And the N?

“Nothing. N means nothing. I just put N in there because it would look nice printed on the cassette cover—UN Sun would read serious.” He chuckles at my incredulity.

“Cassette is business for me. [The] more cassettes I sell, more powerful I become.”

So is it all about sales?

“People think it is easy to sell.” He is a bit irritated at my presumptuousness and he is slurring his words, “It is a gift. People just listen to the love song. But I have to make layer upon layer. Why do you love? How do you love? How do you seduce? How do you go mad? I have to build a whole world and if that world is not truthful, people don’t remember, and it has to be true and modern.”

And then he starts talking of U Soso Tham, the first Khasi Modern poet from the early part of the last century. A textbook fixture. So is he doing what Soso Tham tried to do?

“Maybe,” he has an impish smile, “But I sing.”

It has stopped raining and is getting dark outside.

“I think, I read the papers, I imagine, I am a nosey sort of a fellow. I am always curious about people and the world. All of that makes my songs real. And I have no fear. I say what I feel, I say what I hear. Like the song about Statue of Mahatma Gandhi with his back to the secretariat—I wrote it because there is so much corruption. Others are scared to speak.”

His fearless ridiculing of the celebrated and celebrating of the ridiculed have ensured that his songs are shared as proverbial folk sayings. The tribal as a little rat struggling in the jaws of a cat, or the dkhar’s ability to turn Khasi women into dry fish to feed the cat. But ethnographers and linguists are not writing up projects to enshrine him in the pantheon of local culture.

Why don’t the custodians of Khasi culture and identity acknowledge him?

“I don’t care if they don’t like me. They feel hurt because I tell the truth. They must be thinking I am just a singer from the village. But I see how people are alive. How they struggle. I compare them to nong sor—people of standard—city slickers. Village people do much more than the city people yet people laugh at them. I am a countryside singer. Not a country singer.”

The countryside, the site of everything Shillong tries to escape, its smells, its patchwork second-hand clothes. The only way Shillong can understand Sun is by listening to him as a country bumpkin full of double-entendres and ribaldry. Like a sharp listener of the streets and the fields, Bah Sun wields his words not prescriptively, but in ambiguities of description.

“What can you do with double meaning? Anything can have double meaning, like my song ‘Dung Dung’, a love song. I am saying, ‘You pricked (dung) my heart with a rusted arrow, but people understand it as merely dung-dung—poke-poke. Can I stop people from misusing my words?”

He reaches for his packet of Silk Cuts and Cock-brand matchbox and an old aluminium bowl transformed into a makeshift ashtray. He offers me one and we light up. “Never insult your habit,” he quips.

His wife disapproves and yet buys him his cigarettes. Makes him seem like the fun-loving Sun of the past.

“So tell me, what is your profit in all this?” He is quizzing me now.

“As in?”

“All this talking? What would you make?”

I tell him about going rates, if he agrees to publication.

“So if you don’t mind, help me if you can. I am not ashamed to ask for help. My old friends don’t even call on me knowing that I am now Jalieh (Plain rice) not Jadoh (Pork Rice).”

I feel relieved and grateful.

VIII

He reaches for his packet of Silk Cuts and Cock-brand matchbox and an old aluminium bowl transformed into a makeshift ashtray. “Never insult your habit,” he quips.

We would meet again. There would a photo session; he would hold a Bible for a photo, but laugh at the artifice of it all. “Why don’t you shoot me with the newspaper? That would be more real.”

He would turn into a director, instructing me about the perfect camera position to shoot him smoking.

He would ask me to make some biryani for him.

I would hear him peeing.

I would meet his mother-in-law, who would quiz me about my faith. He would soothe her disbelief at my atheism, by telling her, “Kisim Kisim ka log (all kinds of people).”

He would laugh when his ever-laughing companion would insist that I couldn’t name her in my piece. She doesn’t want publicity and she is a bit superstitious.

Last, when I see him, with chocolates to share, he would show me a copy full of scrawly text. “I’ve been writing—I have enough material for two albums, one Jingrwai Pyrthei (Earthy Songs) and the other, Jingrwai Niam (Religious Songs).”

Which one would he record first?

Naughtily, he looks at his companion. “She may want me to bring out the religious album first, but I need the earthy one first.”

(Essay and photograpgs by Tarun Bhartiya. He is a documentary imagemaker, poet and political activist based in Shillong)