On this day 55 years ago, a mail that S.H. Raza writes to compatriot artist Krishen Khanna in another continent shows the former’s reluctance to be into any professional engagement other than painting. “The International House here wants me to give a talk one evening, but I have a dislike for lecturing,” Raza, three years elder to Khanna, writes from the United States on August 11, 1962. “However my official title is Lecturer in Art. I wish you could take over.”

This string of sentences comes as an appendage to a letter Raza, who had shifted base to the West after having spent formative years in central India, wrote to his close friend a couple of days before that, but could not post immediately. He had August 9 mail, while working as a guest lecturer at University of California on western America.

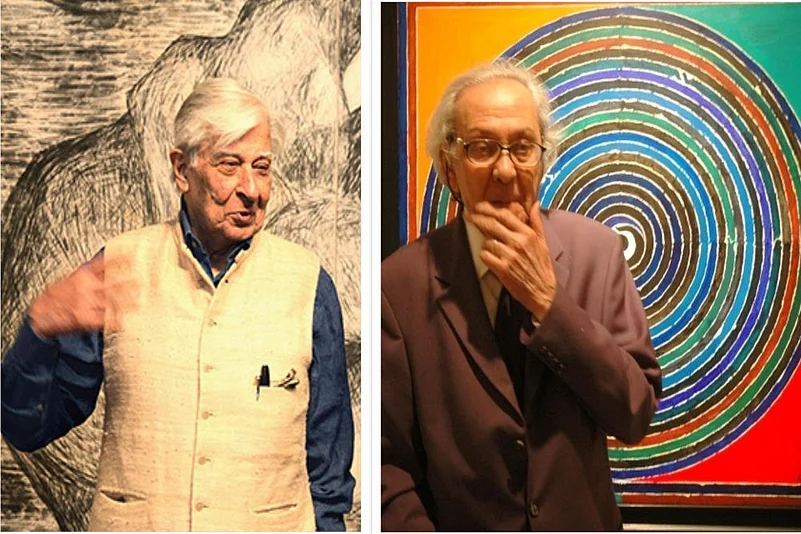

“Here, in Berkeley, there is hardly any art activity except at the University…. We visited the San Francisco Muesum but could not see the galleries,” Raza tells Khanna in a long letter, having been published as part of a book that carries four-and-a-half decades of correspondence from end-August 1956 between the two who went on to become titans modernists in Indian art. “The art department is presenting my work in the gallery at the University,” adds Raza (1922-2016) in that mail to Khanna, who now lives in Delhi and is 93 years old. The 224-page book, My Dear, is the first in a series of Raza correspondence featuring the letters the late artist wrote to friends of his generation in the field of culture.

Khanna’s reply (dated August 18) is still longer. The painter, who was born in Lyallpur close to Faisalabad in what became Pakistan after the 1947 Partition, focuses on an oriental trip. “I had a strange experience in Borobudur in Java. I had heard that I was an impressive monument, but when I saw it I was quite amazed. Its enormity and consistency quite overpowered me,” he says. And adds about his own upcoming US tour: “We are planning to stay in San Francisco from the 3rd till the 10th of September…. On the 11th we arrive in Berkeley.”

The book, brought out by the nascent Raza Foundation in collaboration with VadehraArtGallery, also of Delhi (where the artist died, spending the evening of his life), isn’t all about just their personal matters or even artistic pursuits. It mirrors the close watch that both artists kept over cultural developments—particularly in their Indian subcontinent, no matter wherever in the world they lived.

The letters show a logical strengthening of the bonding between the pals, whose common interest converged largely on visual art. The correspondence, by and large, doesn’t make too obvious the admiration Raza and Khanna had for each other. Even so, there are glimpses of it.

Poet-essayist Ashok Vajpeyi, who was close to Raza and is the founder-trustee of the organisation named after the artist, notes that the correspondence “also constitutes an informal record of what some of most creative minds of India thought and felt about their times, its anxieties and struggles and emerging aesthetics.” Vajpeyi uses the word “their” in a sense beyond the two, because the foundation is proposing to publish more such documents.

The Raza-Khanna correspondence often banks on how their works are progressing and where all they are being shown and how, and the kind of feedback. They are predominantly centred round one’s own artistic travails and achievements (often exchanging samples of artworks as slides and photos) and personal issues (that are sometimes professional too). There were occasional traces of gossip too.

The ethos of a pre-email period comes in fascinating vividness. The necessity for artists to make money also finds a mention. As they succeed in life, both artists show keenness in charity and national welfare.

The first bit of tension in personal life comes in 1965 when Raza tells Khanna about a problem the former had developed with vision. “Since this summer I have been very worried about my right eyes,” he writes, to which the reply comes promptly: “Renu and I are deeply distressed at the trouble…” Raza had married Janine Mongillat, a French artist (who died in 2002).

The book, also for the sake of authenticity, shows select letters in their original format—either independently (in singles or collages) or imposed below the printed lines. They act as windows to the handwritings of the two masters, what with Raza’s looking a bit arty compared to Krishen’s, whose rather clumsy cursive letters ironically tend to contrast his deftness on the canvas.

By 1987, subtle references to their ageing come. Khanna says, “I hope we can meet before we become too old (which in my parlance means 100)!”. By the year 2000, there is a reference to phone talks—something that became common in conversations in a fast-changing world thence.